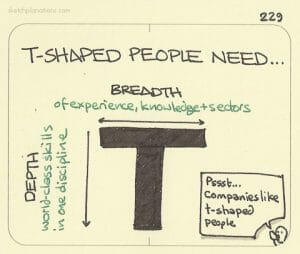

A product manager is simultaneously none of these six things and all of them at the same time. Not all of us get to work in organisations that are set up with specialists in each subject area. Being the generalists we tend to be, working in a smaller organisation is great for allowing us to expand our roles to fill in the gaps. But while these are things we need to be able to do, none of them should ever be our primary focus.

A product manager is simultaneously none of these six things and all of them at the same time. Not all of us get to work in organisations that are set up with specialists in each subject area. Being the generalists we tend to be, working in a smaller organisation is great for allowing us to expand our roles to fill in the gaps. But while these are things we need to be able to do, none of them should ever be our primary focus.

Product manager is a job title that’s used so frequently and in so many different contexts that it’s worth trying to define it by underlining a few misconceptions of what our main responsibilities are:

1. A product manager isn’t a techie

Or a developer or the IT guy (beautifully described by Jock Busuttil in his fantastic product management book as, “the guy swearing under the desk with a network cable.”)

A product manager is a commercial role, not a technical one. It’s unusual to come across product managers that aren’t interested in technology and like Ken Norton suggests, that knowledge is necessary to understand what’s possible. Understanding what’s possible allows us to avoid making unreasonable demands on our developers. However, the need to understand what your company can sell is vastly more important.

In the context of the two Steves, Wozniak was the tech and Jobs was the best product manager of our generation. He’s often — uncharitably I think — referred to as the sales and marketing half of the relationship but he did a lot more than just sell the product after it had already been built.

He tinkered with programming and home-brewing computers, but his main contribution was applying technology to solve problems at an unfathomably vast, transformative, profitable scale: mouse-driven GUI for the desktop computer, the 1-inch drive that gave us “1,000 songs in your pocket“, multi-touch gestures on capacitive screens in mobile phones and even CGI animation when he funded Pixar to create the first Toy Story.

That’s not to diminish the importance of sales, marketing and/or developers – whose work is valuable – but the product manager fulfils a different role.

2. A product manager isn’t a marketer

A product manager needs to be able to articulate what their product is better than anyone else but they don’t have to be the ones who explain those benefits directly to the customer. We only need to put our knowledge about the customer problems helping those doing the promotion and selling to understand what they are selling and why.

The fact that sales and marketing have that direct relationship also makes them very useful to product managers; they hear the objections, know the pain points and know what will close the deal.

This makes our relationship with marketing and sales a symbiotic one in which helping them to do their jobs allows them to help us to do ours.

3. A product manager isn’t a product owner

In scrum, a product owner should have exclusive ownership over prioritisation for all backlogs (e.g. product and sprint backlogs). Following this to the letter means sometimes, product managers end up being heavily involved in execution and delivery.

However, ‘owning’ backlogs is actually about decision-making. Story-writing, drafting roadmaps and refining backlogs is useful but I don’t think there’s anything that could be better for a product manager’s productivity than allowing someone else to absorb the admin side of these tasks.

We are often mistaken for project managers but theirs is to attempt to answer the tiring ‘when will it be done?’ Ours is to worry about, ‘should it be done at all?’ The former is tactical; the latter isn’t always time sensitive.

4. A product manager isn’t an agile fascist

Agile and lean are all-the-rage and de rigueur in modern software development. The next statement will probably be an unfashionable one but agile isn’t the only way to build web products and waterfall isn’t evil. Product managers shouldn’t be wedded to cult agile.

In the context of an organisation that’s been around for decades having figured out what it sells in year two, a linear process with no variation or unpredictability is the most efficient way to carry on building what they build. The whole concept of ‘lean’ came from mass production where the name of the game was finding minute improvements that aggregated into big overall gains. This was done through repetition.

Agile has it’s place in sexy startups or in new product lines but if it’s a well-known problem with a well-known solution and you can say down to the hour how long what you’re building will take, then it should be run like a ‘project‘. Shoe-horning agile onto it and pretending to break everything into ‘sprints’ so you can pay lip service to the agile gods is somewhere between dishonest and delusional.

By all means, borrow useful tools like daily stand-ups which give development a nice, metronomic cadence but if you work for SpaceX or NASA, you have to accept that a huge amount of work is required up-front and in some cases, with no input from the customer for example in the case of LOCOG and the 2012 Olympics opening ceremony. You have to accept only getting one chance and that there will be a ‘final’ product.

Commander Chris Hadfield spent four years training for his space mission to the ISS and those four years were his only comfort when he found himself hurtling towards the earth at 18,000mph fixating on the question, “what’s the next thing that’s going to kill me?”

5. A product manager isn’t a data analyst or user researcher

These wonderful colleagues do the groundwork and collect all the data. They can set up all the experiments/panels/workshops and run all the spreadsheets. The product manager’s job is to interpret the data, work out what the next question to ask is then turn the answers into something customers want to buy.

A product manager can be an analytics ninja but if we go back to original, unadulterated ‘lean’, the goal was eliminating activity that didn’t deliver value to the end user. Value for the end user is the one thing we are more accountable for than anyone else. We have to help our internal stakeholders to understand why each piece of insight is important i.e. showing them how applying that insight will work for the business.

Your internal stakeholders have to be on board with what you’re trying to do and they have to understand why you’ve made the decisions you’ve made. They don’t need to ‘sign off’ everything but they need to have mentally gone through the same steps you went through before you chose a course of action. And it is in taking them through that narrative that you will be able to realise your vision without resistance.

So understand the data, apply it and share but you don’t have to collect it all yourself.

6. A product manager isn’t the boss (or la patron)

Great product managers understand influence; they don’t coerce or dictate; they persuade and inspire. In his TED talk, Simon Sinek describes how we can do this by starting with the question ‘why’: “Why does it matter?” “Why should anyone care?” “Why is it worth doing?”

We have to figure out ‘why’ and explain it to everyone else. We don’t have to come up with the best ideas or follow what’s in our heads with no concession or compromise. Product management is about getting the best from the team you have and sometimes that means staying away from centre stage.

Conclusion

The ultimate aim should be doing just enough to show why those skills are necessary for successful products and like any good CEO, you need to ‘fire yourself’ from that role as soon as you have the resources to allow someone else to take it on while you get on with the real ‘why’. You need to be able to do it if noone else can but always remember that individually, they are just parts of our jobs rather than the whole.

Knowing how to do other team members’ roles allows you to understand where their value lies and what they care about. Being able to empathise and frame your conversation around their needs will make you a more persuasive leader. This is not the same as stepping in to do everything or telling them how to do it – which are both easy traps to fall into. What it actually means is trusting other people to play their part in the team’s success. We become more effective as product managers when we accept that we need other people to get things done and start trying to figure out the best way of doing that.

So if you run a company and have been trying to decide whether to hire a product manager or if you already have and are trying to work out whether they are doing their job, consider these six things. If you’re looking for someone who only does one of them, a product manager probably isn’t what you need. But if you’re looking at a CV for someone who has experience in most of these areas, it’s probably worth starting a conversation with them.

Comments

Join the community

Sign up for free to share your thoughts