In their new book, Build What Matters (£26.99), Rajesh Nerlikar and Ben Foster introduce you to their methodology for becoming a product-driven company. Through their tested strategies, stories of personal success, and case studies from their product advisory clients at Prodify, you’ll learn how Vision-Led Product Management helps you achieve company objectives by meeting both current and future customer needs.

In their new book, Build What Matters (£26.99), Rajesh Nerlikar and Ben Foster introduce you to their methodology for becoming a product-driven company. Through their tested strategies, stories of personal success, and case studies from their product advisory clients at Prodify, you’ll learn how Vision-Led Product Management helps you achieve company objectives by meeting both current and future customer needs.

As a Mind the Product member, Ben and Rajesh are giving you a sneak peek of Chapter 1: Why Product Isn’t Working and Chapter 2: The Solution. These chapters cover everything from the top 10 dysfunctions in product management and how to know if you’re product-driven, to Vision-Led Product Management and a link to useful resources. Enjoy!

Chapter 1

Why Product Isn’t Working

Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. —Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

We see hard-working product teams struggling all the time, even under the best of conditions. While there are many things that can go wrong, we’ve identified the most common dysfunctions in product management. If some of these seem familiar, then this is the book for you.

Top 10 Dysfunctions in Product Management

Here are the top ten dysfunctions in product management from our perspective:

We’ll delve into each of these dysfunctions so you can see if they are representative of the challenges you’re dealing with in your company. You may find you’ve experienced most or even all of them at one time or another. Rest assured that doesn’t signal incompetence or imply your product team is deficient or unskilled. On the contrary, these issues are so prevalent that almost everyone who has worked in product management will have struggled with them at one point or another. As you read each of them, mark which ones ring true at your company.

We’ll delve into each of these dysfunctions so you can see if they are representative of the challenges you’re dealing with in your company. You may find you’ve experienced most or even all of them at one time or another. Rest assured that doesn’t signal incompetence or imply your product team is deficient or unskilled. On the contrary, these issues are so prevalent that almost everyone who has worked in product management will have struggled with them at one point or another. As you read each of them, mark which ones ring true at your company.

Pattern #1: The Hamster Wheel

On a hamster wheel, all that matters is continuing to run, even though you’re not getting anywhere. Similarly, we find that sometimes product teams are almost entirely focused on hitting deadlines with little regard for the outcome. When desired outcomes are unclear or difficult to measure, leadership tends to concentrate on output instead, but what’s the use of spending months developing a product that no customer wants or is willing to pay for, whether you hit the deadline or not?

If you’re delivering the wrong thing, it doesn’t matter how efficiently or quickly you deliver it, and your output isn’t necessarily meaningful or beneficial unless you’re creating value for the customer or the business.

Compare these two questions, and you’ll see the difference in perspective.

- Did you ship that feature on time? (output-oriented)

- Did that feature deliver value to customers and grow revenue? (outcome-oriented)

Ben’s Story

MEASURING LINES OF PRD

During my time at eBay, from 2001 to 2005, product management was run by a few different leaders. When I first joined as an entry-level product manager, Marty Cagan was leading product management and design, and there was a true appreciation for the innovative role that product management played. After he left, the engineering leader stepped in to fill his shoes. Her perspective was that product management’s job was to feed the engineering beast, producing volumes of product requirements documents (PRDs) that would keep thousands of developers busy. The joint product and engineering team became extremely efficient at delivering lots of code, less so at delivering consistent results.

With no clear way of holding product managers accountable for outcomes, she defaulted to pure productivity metrics. Product managers were actually issued a quota for lines of PRD written per quarter, and that quota was increased each quarter to demonstrate productivity gains to the COO.

The consequences were predictable. Product managers worked excessively long hours to produce monster PRDs for overdesigned features. I personally wrote a 240-page PRD that required an entire week of meetings to hand off to the engineering team. Looking back, I’m confident the same results could have been delivered with a simplified product design and less documentation, which would have saved engineering capacity and allowed us to address the next business opportunity. Believe it or not, at the time, I was actually proud of myself. In what should have been a “teaching moment,” I was applauded for the time I put in and the amount of work I created for others.

Pattern #2: The Counting House

In the counting house, the focus is entirely on internal metrics with no regard for customer success. Many product teams become obsessed with internal metrics like revenue growth, monthly active users (MAUs), and customer retention. Sometimes, they even fabricate new metrics because they’re convinced that if some internal number looks good, it must mean the product is a success.

The truth is, most internal metrics are trailing indicators of a product’s success, and therefore shouldn’t be the primary focus of product management. It’s far better to answer the question, “How can we effectively deliver greater value to our customers?” If you can answer that question and create a good business model around the answer, your internal metrics will almost always follow suit.

Pattern #3: The Ivory Tower

In the ivory tower, product teams become so removed, so far above the customers that they start thinking they know their customers better than the customers know themselves. Consequently, they never really talk to their customers, which means they risk building a product no one wants or needs. Just because a product team falls in love with its own solution doesn’t mean customers will.

Furthermore, a lack of customer-driven insights can lead to a spiral of mistrust between product management and other stakeholder groups in the company. Product management feels like they are building the right product (though they may not be), so when the product doesn’t perform well in the market, they assume the fault lies elsewhere. Go-to-market teams believe product management is to blame for not being responsive enough to their feedback. Engineering loses confidence that their efforts are worthwhile, and they question every new priority that’s presented. From the CEO’s perspective, it’s unclear why the budget allocated to research and development (R&D) isn’t delivering results, and every attempt to figure it out yields more finger-pointing and excuses.

Rajesh’s Story

ASSUMING WHAT USERS WANT

Spring 2014 was an exciting time for me. Not only was our first son due, but I also saw two exits from the startups I worked for. Opower went public in April, and HelloWallet was acquired by a strategic investor, Morningstar, in May. Nervous about working for a “big” enterprise like Morningstar, I immediately decided to launch a dating app my buddy and I had been talking about for years. The idea was simple: matching people based on the actual places they go because people are more likely to be interested in someone who goes to the same bars, restaurants, parks, museums, and ballparks. Location-based check-ins on Facebook and Foursquare (Swarm) were rising, so we pulled data from those platforms. I called the app Wentroductions, and to this day, I cringe at the awkward name choice.

While deciding on the scope of the minimum viable product (MVP), I used dating app feedback from my friends and my own experiences, but I didn’t conduct enough customer discovery to validate our experiences or to understand why someone would use our product over more popular apps like Tinder. Instead, I spent my nights and weekends writing user stories and putting together wireframes so my cousin’s software development firm in India could build the MVP. My buddy and I formed a company and put in our own money (I decided to “let it ride” with my two recent exit earnings). About five months later, the app was nearly ready, and I started running Twitter ads to get users.

And then I realized my mistake. We had ten to twelve users in the first two weeks, but dating apps don’t succeed if they can’t match you with someone soon after you sign up. So I asked friends and family to join because I didn’t want to use the common “seed and weed” strategy of creating fake profiles and then removing them when enough users sign up.

I probably don’t have to tell you how this ended. Wentroductions never took off with users, and while the app looked and worked great, the product failed as I sat in my ivory tower. It had been years since I’d last used a dating app, yet I still thought I knew what users wanted. To this day, my best piece of advice to anyone who thinks a new product should exist in the world is to build a simple landing page and create an email waitlist based on a few simple feature descriptions to learn what resonates with real customers.

Pattern #4: The Science Lab

In the science lab, product teams tend to focus all of their efforts on highly measurable yet superficial improvements to their product. Collectively, these small-scale A/B tests don’t do much to innovate or add customer value.

Here’s a version of this problem we often see. A company has a sign-up process on their website, and they want to encourage more people to use it. To do that, they start making a variety of minor optimizations to the sign-up process—changing button colors, tweaking the text, changing the graphics—hoping that something will drive up the level of engagement. In general, these kinds of changes provide no actual value to customers and have very little to do with engagement.

In the last few years, we’ve seen optimization become the be-all and end-all for more and more companies rather than a facet of a balanced product development roadmap. The assumption is that making improvements to existing solutions is the one thing that will drive results, but even effective optimizations can’t take the place of real innovation. Companies that are constantly trying to eke out more value from their existing solutions run the risk of stagnating. It’s almost impossible to A/B test your way to real innovation.

Pattern #5: The Feature Factory

What does a feature factory build? Features. When is a feature factory done building features? Never. The problem with being a feature factory is that there’s always the next one to build. Product teams fall into this trap because they are led to believe by customers or internal stakeholders that if they just had this one next feature, they will close incremental deals or keep customers who might otherwise leave.

Sometimes, it works out that a specific missing feature is holding the business back, but more often than not, the team discovers that yet another feature is also needed. Even when the newest addition does, in fact, fully resolve a customer’s issue such that it saves an account or lands a new deal, it’s only one. All the while, entire market opportunities are missed because the product doesn’t deliver sufficient value to prospective customers who lack a voice (or won’t bother speaking). In fact, the addition of too many features can weigh down the user experience (UX) so much that new customers can no longer comprehend the product, which results in a net negative outcome for the company.

Ben’s Story

THE COLOR-CODED ROADMAP

I vividly remember joining Opower as the VP of product in early 2010. In my second week, the board requested to see a product roadmap. Scrambling to deliver, the obvious starting point was learning from the team what had already been planned. In doing so, I discovered two surprising facts: 1) there was no roadmap, and 2) the company had already contractually committed nearly all of the engineering capacity for the next six months to building a hodgepodge of one-off features for newly-closed accounts.

These weren’t the priorities I wanted, and in fact, no one else in the company wanted them prioritized either, but in an effort to close business, they had acquiesced. I needed to communicate to the board and our employees not only what our priorities were but why, so I created a roadmap document that showed all of the features we were required to build over the next six months colour-coded in yellow and all the more meaningful improvements we were excited to deliver afterward colour-coded in blue. That way everyone saw the reality but also had a glimmer of hope: after heads- down work for six months, we would be in a position to really innovate.

Sadly, that’s not what happened. Six months later, we had indeed delivered against the client commitments, but the colour-coded roadmap still looked exactly the same. In that time, we had continued to make new client commitments, defer- ring our intended priorities another six months. This would have continued into perpetuity if we hadn’t solved the underlying problem. We were a feature factory! With some great cross-functional teamwork, we were finally able to break away from this pattern. Later in the book, we’ll discuss the resolution and finish this story.

Pattern #6: The Business School

Business school is where you go to analyze business but not to actually do business. Similarly, product teams can get so wrapped up in overanalyzing everything that they avoid making tough but essential judgment calls. When it comes to prioritization, some product managers are tempted to get so technical and mathematical that they lose perspective.

There’s a process that seems to make sense to product teams. They sit down and draw up a list of all the features and improvements they want to make to their product. Then they work with the finance team to generate estimates about the specific business impact of these features. Finally, they meet with the engineering team to figure out how much effort it’s going to take to develop them.

Having done that, they typically conduct net present value (NPV) or return on investment (ROI) analyses for every feature or improvement, do scenario-planning, and create spreadsheets that reveal the estimated monetary impact of each potential feature divided by the amount of effort it will take to develop. Whatever winds up with the biggest number gets top priority, and they declare, “The mathematics have spoken! Our product decisions have revealed themselves!”

It sounds great in theory, but in reality, no product decisions are being made at all. The initiatives that show the highest estimated impact are the ones that were modeled using the most outrageous assumptions, and usually only the lowest-effort improvements end up above the cutline. All the while, customers and the larger business strategy are completely ignored. Arming oneself with specious ROI estimates at a committee meeting is a poor substitute for making the right strategic decisions to maximize the impact of product development.

Pattern #7: The Roller Coaster

A roller coaster is all about fast thrills and wild, whiplashing movements. They can be a lot of fun, but they aren’t a good model for effective product management. Investors and executives like to see immediate results, and when those results don’t materialize right away, they can be tempted to pivot suddenly, resulting in whiplash for the product team.

This problem comes from setting a time horizon that is too short. For startups, a lack of patience is often the result of having a very short runway. They have to get something up and running fast so they can raise the next round of funding, or they need to start producing revenue right away. Of course, everyone wants to make fast and efficient progress, but providing insufficient opportunity for success will result in false negatives that can lead product managers astray. When an otherwise healthy “fail-fast” mentality is taken to the extreme, it can stifle innovation.

“We think this new feature is a good idea,” a product manager might say. “To avoid overinvesting, we’ll first launch a lackluster version of it. If it doesn’t get overwhelmingly positive results immediately, then we’ll know it’s not the right direction for our product.” Daisy-chained together, these false negatives result in a headache-inducing roller coaster ride for product development that ends up in exactly the same place it started.

Pattern #8: The Bridge to Nowhere

Engineers love solving future problems with technology. That can be a good thing when taken to the right level, but it can also be taken too far. They get excited about developing the infrastructure to get the product just right, but sometimes, they can end up overengineering a product, trying to account for future needs that aren’t relevant—and may never be. As a result, product development can get so bogged down that a great product that would have delivered meaningful customer value never sees the light of day.

Sometimes, it’s better for engineers to tolerate some reworking of the product down the road, as long as the foundational elements are in place, rather than solving numerous theoretical and potential problems. Imagine if a team of engineers designed and constructed a bridge over a river to connect a city to a wilderness area where another city might someday exist. They invest a tremendous amount of time, money, and resources to construct a bridge sturdy enough to support a multilane highway under the assumption that eventually there will be a lot of traffic, but what would be the point if the second city never got built? Why not wait until at least a small town has developed on the other side of the river, and then build a small, one-lane bridge to connect it, with the understanding that if the town grows into a large city, the bridge can be expanded and reinforced?

Every tech company has to invest in the underlying technology of its product, but there must be sufficient confidence that it will offer tangible value to the business or the customer within a reasonable time frame to warrant investment now. Scaling for a future that never materializes is a futile exercise no tech company can afford.

Pattern #9: The Negotiating Table

Sometimes, product meetings can turn into a negotiating table, as the product manager tries to give everyone what they want. Product managers often believe that success means keeping all of their stakeholders happy—or, at least, minimizing their unhappiness—but when teams and individuals throughout the organization collectively want more than engineering can potentially deliver, this becomes practically impossible. A list of inbound demands might look like this:

- The CEO has a pet product idea.

- Sales wants five other features.

- Engineering feels it’s critical to tackle some technical debt.

- Customer support needs a bug fix.

How can the product manager satisfy all of these requests in a timely manner, so they get that all-important pat on the back from everyone?

It’s a bit like playing a game of high-stakes Tetris, as product managers try to fit all of the incongruent requests together. In a sense, they wind up prioritizing to avoid discomfort with the people they see every day in the office. Of course, nobody wants their colleagues mad at them.

However, it’s not a leader’s job to give everyone what they want, and, in fact, true leadership requires making some unpop- ular decisions. Product teams find themselves in the negotiating table situation when the organization misunderstands product management’s chief purpose. It’s not the primary role of prod- uct management to help sales hit their quota this quarter. It’s the role of product management to make it possible for sales to sign up for higher quotas than anyone thought possible farther in the future. When product management prioritizes the right things for the customer, they help every team, whether those teams realize it or not.

Pattern #10: The Throne Room

Sometimes, the founder or CEO just can’t let go. They feel compelled to make decisions about anything and everything important in the company, and they give their team very little ability to call their own shots. Because their instincts got them to where they are, they think it will continue to carry them for- ward, but at a certain point, instinct doesn’t scale. Their job title becomes a trump card any time they want to override a creative decision, and they might not even bother to clarify the rationale when they throw their weight around.

They fail to drive alignment around the product direction, so no one really understands what they’re doing or why. In these kinds of situations, the CEO typically changes their mind frequently, sometimes with little notice, and usually with no real explanation or justification. Every request is treated as priority number one, and the product manager is expected to give them 100 percent of their attention.

It’s an impossible situation for a product team that prevents the scaling of the company beyond a single decision-maker. There must be a clear framework around prioritization that everyone in the company understands, so every initiative can be properly evaluated to determine if it contributes to the end- state customer vision and ultimate success of the company.

Ben’s Story

CONSTANTLY CHANGING PRIORITIES

When I joined Adchemy, a twenty-five-person startup, in 2006 the company had already built ingenious machine learning technology capable of generating and optimizing billions of ads and landing pages every day. The promise of that technology led to multiple funding rounds and a $400 million valuation in 2009.

The difficulty was in converting that technology into a viable product in the competitive ad tech space. Do you sell it to publishers? To advertisers? To agencies? Should it be applied to paid search or display ads or landing pages? Do you package the technology or use it yourself to outperform other affiliate partners delivering online leads? As I moved up the ranks to eventually lead product management and design at Adchemy, I needed clarity, or at least agreement, from the co-founder/ CEO on which of these paths we should choose.

The CEO was exceptionally good at setting a single priority and aligning everyone to it. The only problem was that the singular priority changed like clockwork every quarter. Rather than committing to a path, he vented frustrations down the chain about the (unsurprising) lack of progress on the paths not taken. My team was forced to shift gears frequently, and with very little rationale offered for the hard pivots he demanded, rallying the troops proved an impossible task. Seeing the writing on the wall, I eventually left and the company was ultimately sold to Walmart Labs with no return for investors.

SCORECARD

As you’ve read through these ten dysfunctions of product management, at least a few have probably hit close to home. It can be a useful exercise to assess your organization against each one, so we’ve created this table to help you do just that. Give yourself a point for each problem that you are struggling with in your company, then add up the total and see where things stand.

Ten Dysfunctions of Product Management: Self-Assessment

- The Hamster Wheel: output over outcomes

- The Counting House: obsession with internal metrics o The Ivory Tower: lack of customer research

- The Science Lab: optimization to the exclusion of everything else

- The Feature Factory: an assembly line of features

- The Business School: overdependence on data and spreadsheets

- The Roller Coaster: fast-paced twists and turns

- The Bridge to Nowhere: overengineering for future unknowns

- The Negotiating Table: trying to keep everyone happy

- The Throne Room: whipsaw decision-making from the person in charge

SCORING

0 points: Wow! Maybe you should write a book on product management.

1 point: Amazing! You’d be valedictorian of your product class.

2 points: Not bad. You’re keeping up with other product teams.

3 points: Hmm. You’ve got some work to do.

4+ points: Oof! You’ve got your work cut out for you. Take detailed notes as you read this book and make specific plans for how you’ll fix these dysfunctions at your company.

Think about the impact it would make if you resolved all of those dysfunctions in your organization. Consider all of the engineering potential and creative energy it would free up. Now, consider the unmeasured cost of not dealing with them. Your engineers are probably some of your highest paid, highest value employees, so if their effort isn’t aligned to the right activities, it’s probably costing you more than you realize.

THE COMMONALITIES

While these dysfunctions may seem like ten completely different problems, they fall under just three basic themes:

- Internal focus is drawing too much attention away from delivering meaningful customer value.

- The product team is so busy playing defense or has so little authority, there is no time left for ideation and innovation.

- The desire for short-term directly measurable business outcomes results in only superficial changes being prioritized.

In essence, these themes are all ways that a company naturally fills gaps that could be filled with a clear direction and path for the product. When we spoke with Gibson Biddle, former VP of product management at Netflix and highly regarded product management thought leader, he explained this succinctly: “Product leadership is defined as inspired communication of a vision. The majority of problems faced by most product teams are solved through strong leadership.”

Creating an end-state customer vision for your product is how to resolve each of these ten patterns of dysfunction, both by uprooting them and by preventing them from taking hold in the first place. It also prevents product manager burnout. These problems exact a heavy toll, and when they mount up, even a hardened product manager can become so worn out and discouraged that they quit. We’ve seen this happen firsthand, so we always love it when we can help a product manager overcome these challenges and ease the burden.

ACTION CHECKLIST AND RESOURCES

We want this book to be actionable and helpful to everyone who reads it, so at the end of each chapter, we’ve included a link to an action checklist and resources that will make it easy to take those actions. That way, you can apply the concepts from each chapter to your own product(s).

Visit buildwhatmattersbook.com for an action checklist and additional resources, such as a team-level scorecard for the ten dysfunctions in your organization.

Chapter 2

The Solution

The best defense is a good offense.—Pretty Much Every Strategist Ever

When you look at the problems from the previous chapter, it’s easy to see why so many product teams are overwhelmed, frustrated, or confused.

In this chapter, we will reveal a framework for resolving those top ten dysfunctions, and then, throughout the rest of the book, we will delve into the actual process for creating your vision and putting together the right team and processes to implement it effectively. In the end, we’re confident it will be transformative for your product management practice.

It all starts with becoming truly product-driven.

BEING PRODUCT-DRIVEN

Most of the founders, CEOs, and product managers we speak to either claim that their companies are product-driven or say, “We’re not there yet, but we certainly aspire to be.” However, when we start probing for specifics—What does it mean to be product-driven? How do you know you’re moving in that direction? How will you know when you’ve achieved it? —more often than not, we get blank stares in return.

This is indicative of a larger problem across the entire spectrum of the tech and startup world. Company leaders want to be product-driven, but they don’t know what being “product-driven” (or “product-led”) means exactly. There are two core operating tenets of being a product-driven company:

- You address a customer’s need through a solution applicable to the broader market.

- Product decisions come first, and other decisions follow.

Let’s unpack each of these.

A Solution for a Broader Market

The first tenet of a product-driven company is that it builds solutions that work for an entire market segment, rather than for one customer at a time. In any given market, each potential customer will have their own individual needs, preferences, priorities, and trade-offs they are willing to make.

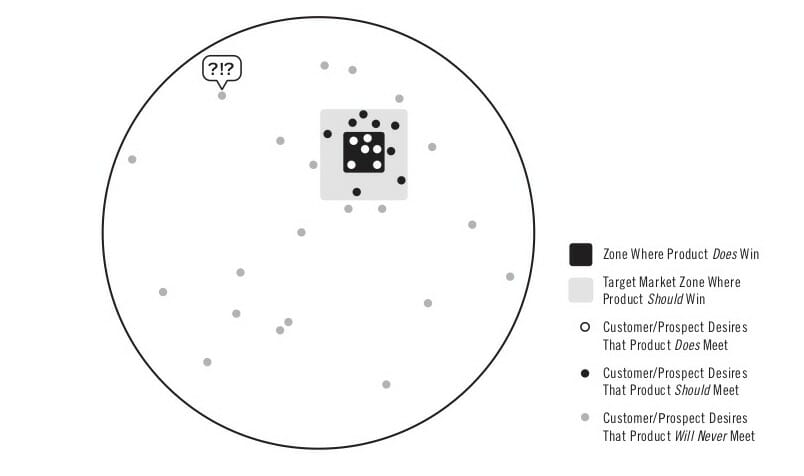

Imagine you could make a map of all the potential customers in your market and their respective desires for a solution and plot them as dots. Some customers would have very similar desires, and other customers’ opposing preferences would place them far away from one another.

Different customers appearing in different areas of the map represent how their ideal solutions are also unique. In order to perfectly satisfy every customer’s desires, you would have to deliver a specially tailored solution for each of them, which is exactly what services-driven companies do. Those solutions could be delivered via ongoing services (as a consultancy does) or by delivering bespoke technology solutions, as represented by the squares on the map.

Systems integrator Accenture is a quintessential services-driven company. They want to be able to say yes to any request for proposal (RFP) a customer submits. When a potential client comes to them and says, “We need this project done for us,” they bend over backward to fulfill that request and capture the revenue. In practice, they end up providing many different one-off custom solutions to keep new and existing customers happy. This is appropriate in certain situations, when each customer’s need is highly specific and when the solution needs to work in an exact way.

A product-driven company takes the exact opposite approach from a services-driven company. They never build a custom solution for an individual customer. Instead, they build a product that they expect multiple customers to adopt once available.

In theory, product-driven companies gamble that the product they’ve created will address the needs of many customers, including those they haven’t yet met. While a services-driven company first needs to meet the customer to understand their individual needs so they can custom-build a solution for them, a product-driven company creates a product based on an educated guess about what the needs of future prospective customers will be. This changes everything about the company’s operations and places an enormous burden on product management to get it right.

For most prospective customers, the product will be less than perfect in some way. Does that mean the product will only be a viable solution for the narrow range of customers whose ideal desires are met by the product? No! Prospective customers who can imagine some product improvement will still buy and be very satisfied with the product. The product doesn’t need to be perfect for every customer—it just has to be the best solution available.

This is where companies that aspire to be product-driven often get it wrong: they ask existing customers what they want the product to do that it doesn’t currently do. There will always be a million answers to that question, and sometimes those answers will be in direct conflict with one another. You will never finish building a product that makes every customer in the target market perfectly satisfied. After all, that’s the approach of a services-driven company, not a product-driven company. To avoid unintentionally becoming a services-driven company, you must say no to most product requests.

The reason we’re providing so much theory about being product-driven is because it’s absolutely essential to embrace the reality that there will always be gaps between how your target market wants your product to work and how it actually works. This point is so important, it bears repeating:

Embrace the reality that there will always be gaps between what your customer wants and what your product does.

Those gaps aren’t just tolerable, they are necessary. If you were to successfully close all of them, you would either fork the code so much, or you would end up with a product so bloated that it would become unusable due to its complexity. If the gaps between your product capabilities and your customers’ desires are small enough that the product is clearly the best option for them, and will likely continue to be for the foreseeable future, then don’t get distracted by their requests.

Of course, you are bound to get feedback from customers who are dealing with gaps so wide that they cannot use the product, or they can find a better alternative. The important consideration in this case is whether or not those customers are part of your target market.

None of this is to say that you shouldn’t listen to your current customers. However, as a product-driven company, how you interpret what your customers tell you matters greatly. If there is a way to address the feedback such that it will benefit other customers and the business as well, then doing so may be worthwhile as it will get you closer to product-market fit (PMF). If what you’re building only benefits the customer you’re talking to but is unlikely to benefit anyone else, then you’re listening to your customers but not being product-driven.

Let’s look at an updated version of the customer desires map to illustrate how a product-driven company operates.

- The black square is the portion of your target market that your product currently serves well. The white dots are the customers and prospects for whom your product is a clear winner.

- The gray box represents your broader target market, and the black dots inside of it represent the desires of customers and prospects that you aim to serve as you improve your product to expand its reach. In order to win them over, you need to understand their desires and close the gap between what the product does today and what they want it to do.

- The gray dots outside of the target market box are the desires of customers and prospects for whom the product was not designed. Of course the product won’t work as they would like; it was never meant to.

This graphic can also help explain how a product-driven company interprets feedback from customers and prospects. A product-driven company has a clearly defined target market (the gray box) and knows which segments of that target market the product currently serves well (the black box and white dots). Knowing their product will attract all three types of customers, a product-driven company first determines which type of customer they’re talking to before deciding how to respond to the feedback.

- If the feedback is coming from someone whose desires are met by the current product (a white dot), they need to decide whether responding to that feedback is going to help the business through retention or upsells. If doing so carries no significant business benefits, then the company may be chasing rainbows by working down a never-ending list of potential product enhancements. While it may be tempting to drive customer satisfaction, customers usually just end up fixating on the next missing feature instead.

- If the feedback comes from someone in the target market (a black dot), the product-driven company will synthesize that feedback to determine how to improve their fit and deepen their market penetration by better addressing a wider range of customer desires.

- If the feedback comes from someone outside of the target market (a gray dot), the product-driven company knows to disregard the feedback, unless they are intentionally expanding their target market to cover that type of customer. You see this as the gray dot in the top left, the customer who bought your product intending to use it for a purpose it was never meant for and who vents frustrations in the form of demands and threats to abandon the product. It’s hard to do, but a product-driven company will let them go.

Product Decisions Come First

Think of a company as a series of interoperating gears. Where the gears mesh is how the functional teams work together. With any system of gears, there’s one gear that has the drive—the one connected to the motor.

The second core operating tenet of being a product-driven company is that the product is the driver. This means figuring out what the market needs are going to be and constructing a product that will meet them for a broad set of customers. Everybody in the company—sales, marketing, engineering, and so on—rallies around the product strategy. The end-state customer vision provides direction and alignment for the entire team, and product management is responsible for creating that vision and sharing it with all stakeholders.

There are other options besides being product-driven, and depending on the company, those other options may be more appropriate. For example, we would argue that Nike is a brand-driven company, at least for its apparel business. It’s all about getting the iconic swoosh out there and associating the brand with the aspirations of their target customer: emulating celebrity athletes, embracing the mentality epitomized by their trademarked “Just Do It” slogan, and reveling in a spirit of competition and commitment. The other divisions are obliged to follow suit and execute their pieces of that strategy. It is unlikely that any designer at Nike would create a new product and then try to figure out, after the fact, where to fit “that darned swoosh.” A brand-driven strategy isn’t a bad strategy—for Nike.

Certain technology-driven companies, such as those creating artificial intelligence (AI) and augmented reality (AR) capabilities, are also different from product-driven companies because the capabilities they create are licensed by customers to experiment with and explore potential uses. In these companies, technology is the driver, and the other organizations in the company must follow their lead. On the cutting edge of technology, where a market doesn’t exist yet or is very poorly defined, this may very well be the best approach.

However, the most successful tech companies in the world are product-driven. They identify market opportunities and design solutions that directly address broad market needs while providing strong unit economics. Only afterward do they scale massively by investing in underlying technology, crafting smart product positioning, and executing go-to-market tactics that are well-suited to the product and the market. The product drives everything.

Case StudyCROSSLEAD: CONVERGING ON PRODUCT-MARKET FITCrossLead is a platform that helps organizations of all sizes plan, manage, and track progress toward achieving important company objectives. It was founded by Navy SEAL David Silverman, co-author of the best seller Team of Teams, which details the military’s need to become nimbler and more flexible in order to successfully fight Al Qaeda. Many commercial organizations are faced with the challenge of making similar adaptations, but they lack the necessary software tools and frameworks, which CrossLead provides. Nevertheless, the CrossLead team did not see immediate market traction. Prodify began working with CrossLead at a time when its leadership was having difficult internal conversations about how to reach product-market fit (PMF). We facilitated an exercise that helped them identify the right path. As CrossLead’s head of product, Paige Morschauser describes the process, “People tend to look at PMF as just ‘product’ and ‘market,’ but that is an incomplete way of looking at it. It is important to factor economics into the equation and then consider the intersections between all three areas. Prodify provided us with a Venn diagram of these components and the key success indicators within each. We then individually graded ourselves on each metric before reconvening as a group. “We used this exercise to facilitate a discussion amongst key stakeholders and to align on the biggest gap within the Venn diagram. For us, it became apparent that there was a disconnect between the value proposition customers looked for during the sales process and what the product delivered after it was purchased.” This insight redirected the company’s customer discovery priorities. Next, we worked with Paige’s team to develop a new customer research plan to gather further insights from their customers’ perspective. The findings led to CrossLead’s big “aha” moment, which was that the target buyer persona had been defined so broadly that they could never build enough features to satisfy all of their needs. Debates about which features to put on the roadmap next were the result of there simply being no right answer. They zeroed in on a more specific buyer persona and identified the specific unmet needs that CrossLead should address—all achievable with focused product development efforts. According to Paige, “We were able to construct a more strategic roadmap spanning the next several quarters and establish important product development milestones that the whole company could rally behind.” |

HOW TO KNOW WHETHER YOU’RE PRODUCT-DRIVEN

Let’s translate the theory into practical terms. How do you know if you are operating as a product-driven company? There are five traits that we see in every product-driven company, so they serve as a good way to determine whether or not your company is there yet.

-

- In a product-driven company, product management and user experience (UX) design are the closest parties to the customer. They have an obligation to the rest of the organization to have the best understanding of current and future customers they are designing for, and they build that understanding through frequent interactions with users and through working closely with the customer-facing teams internally.

- A product-driven company addresses the needs of multiple customers with a single solution (or a handful of solutions) that works for all of them and therefore spends most of its product roadmap on changes that will benefit many customers, not just one or two. Contrast this approach with a services-driven company like Accenture, which develops tailor-made solutions for individual customers.

- A product-driven company prioritizes the use of technology to solve problems and scale every part of their business. Sometimes, they will initially solve problems manually, but only temporarily—to accelerate time-to-market or reduce risk—as a stopgap until more automated and scalable solutions can be built.

- A product-driven company listens to current customers and prospects to understand the shifts in market demand and predict the needs of future customers. As in the diagram we referenced previously, this means the product team understands which direction the dots are moving and why and is planning to adapt the product to meet changing desires.

- While a sales- or services-driven company succeeds by saying yes to a specific customer, a product-driven company often succeeds by saying no. They recognize that there is a massive opportunity cost in having engineers spend time trying to develop bespoke solutions, which takes critical time and resources away from putting the right product on the shelf to meet future customer needs. The best and most innovative product companies don’t have a problem saying no, and they say it often. As Steve Jobs famously put it, “Innovation is saying no to a thousand things.”

Case StudyCONTACTUALLY: THE POWER OF FOCUSInitially, Contactually was a customer relationship management (CRM) tool for the long tail, allowing small businesses in virtually any industry to manage customer relationships and communications with easy-to-understand, web-based software. The product team had been receiving input from all directions. Customers requested additional features, sales wanted new demo capabilities, customer support identified bugs to fix, and engineering felt an urgency in addressing overdue technical debt. Internal stakeholders became disconnected and frustrated with the product team, yet further trade-offs still needed to be made. At the same time, co-founders Zvi Band and Tony Cappaerthad discovered that they were seeing better traction with real estate agents than customers in other industries, so they were faced with a difficult decision: continue to serve a broad but disjointed customer base or narrow the target market to focus exclusively on the real estate market and risk alienating a subset of (paying) customers. The company made the difficult but ultimately correct decision to focus its product strategy solely on real estate. As expected, several non-real estate customers failed to renew and new customer acquisition dropped as the product became less relevant to the wider market of small businesses and consultants, but the senior leadership of Contactually understood this was the short-term fallout which would soon be followed by several major benefits. The marketing and sales teams consolidated go-to-market activities and concentrated messaging on a specific persona. The product management team was able to filter out all inbound requests that weren’t directly tied to the needs of real estate agents. They filled the space in the roadmap with items that drove customer value, such as:

Rather than building a mediocre product for a broader potential market, Contactually developed a higher quality product for a smaller but still large, accessible market. The results were clear: increases in revenue per customer, willingness to pay, and customer retention. Improvements in growth rate and unit economics eventually led to Contactually’s successful exit, as they were acquired by technology-enabled real estate juggernaut Compass. On reflection, Tony said, “I’ve become such a big believer in the power of focus. Learning to say ‘no’ is crucial to success. In doing so, you’ll lose some customers, and that’s okay.” Zvi added, “Once we focused on real estate, we could concentrate on the cohesive set of user needs and how those translated into larger brokerages as the buyer and user diverged.” Both agreed, “Our only regret is that we didn’t make these decisions earlier.” |

WHY BEING PRODUCT-DRIVEN MATTERS

Why take the gamble to be product-driven? Why not just build according to the specifications of each individual customer, so you never waste time building something nobody is willing to buy? It’s because the potential payoff is massive, both to your customers and to your shareholders.

Why It Matters to Your Customers

Let’s start by taking a look at what being product-driven does for your customers.

First, it helps keep your prices low, and we know a key consideration for customers is price. The cost of delivering a product that has already been built, especially for software, is close to zero, which allows product-driven companies to reduce their prices so much that services-driven companies simply can’t compete. Consider the price difference between TurboTax and H&R Block.

Second, it keeps time-to-value low. Having a solution custom-built takes a long time, but pre-built solutions are available immediately—or, at least, deployment can begin immediately—which again puts services-driven companies at a severe disadvantage. Consider how much longer it would take to have custom furniture made versus grabbing a box from IKEA.

Finally, it offers customers the latest-and-greatest. Cloud-based SaaS platforms offer a major advantage in that upgrades can be made once and propagated to all customers either for free or for a modest price increase. In the services-driven model, the fact that each customer has their own solution means each customer needs to pay for one-off improvements to that solution. The high costs of those changes can make the ROI prohibitively low, eventually resulting in an antiquated or obsolete solution. Consider the complexity involved in upgrading decades-old software systems built specifically for the government.

Why It Matters to Your Company

Being product-driven can also have an enormous impact on your company’s long-term financial success.

First, being product-driven is more profitable because you’ve already built the right product for the next customer. The marginal cost of delivering the same repeatable solution to your next customer as you did for your previous customers is extremely low, which improves unit economics and increases the profitability of every sale.

Second, the valuation of a product-driven company is much higher than that of a services-driven company, with six to eight times higher valuations. Sometimes, the fastest path to higher valuation for a services-driven company isn’t to grow revenue but to transition their services revenue to product revenue. Some product companies with add-on services go so far as to intentionally partner with services companies to keep the lower gross margin (GM) services revenue off their books.

This difference in revenue multiples is due to higher profitability, scalability, and opportunities for product-led growth that come from being product-driven, creating higher expectations among investors, who will value your current revenue higher as a result. Eric Paley, Managing Partner at Founder Collective—and #9 on the Forbes “Midas List” in 2020—explained to us just how important being product-driven is from the investor perspective: “We invest at the seed stage, so the companies we back are still finding their way to product-market fit and massive traction. We have had to get very good at identifying the precursors of success, and one of the most important characteristics of a great early-stage investment opportunity is a product orientation from the founding team. Our most successful portfolio companies are the ones that lead with product, meaning they have a well-formed sense of the target market, how those customers are underserved, the drivers of customer value, and how to address the opportunity with a transformative product.”

Third, product-driven companies have the unique opportunity to employ product-led growth strategies, such as viral adoption and freemium offerings. Consider a product-driven company like Miro. Miro’s product is a collaborative white-board that allows teams to work together remotely, posting ideas, comments, and feedback on a shared space that the entire team can access. With more people working from home following the 2020 coronavirus outbreak, the product has become more popular than ever, and the nature of the product promotes itself. When one person at a company decides to try it, they send invitations to their coworkers. Upon clicking the invitation, those coworkers can access the shared whiteboard and immediately see the power of the product without having to sign up for it, which is an effective way of getting them to discover the value of the product without paying a single advertising dollar or sales commission check. While creating a product-led growth engine like this may be more challenging for some companies than others, it’s only feasible for product-driven companies.

INTRODUCING VISUAL-LED PRODUCT MANAGEMENT

Becoming product-driven is critical for tech companies with big ambitions, and we believe the path to becoming product-driven is to establish a long-term product vision that will meet the needs of your current and future customers.

When we talk about clarifying an end-state vision for your customer, we mean creating a vision for what the future should look like when your product is meeting that new customer’s need—from the customer’s perspective. The vision is not a bulleted list of product features but rather an expression of how the customer will derive value from those features.

The three core components of the Vision-Led Product Management framework, which we will address in Part Two of this book, are key customer outcomes (chapter three), customer journey vision (chapter four), and strategic plan (chapter five).

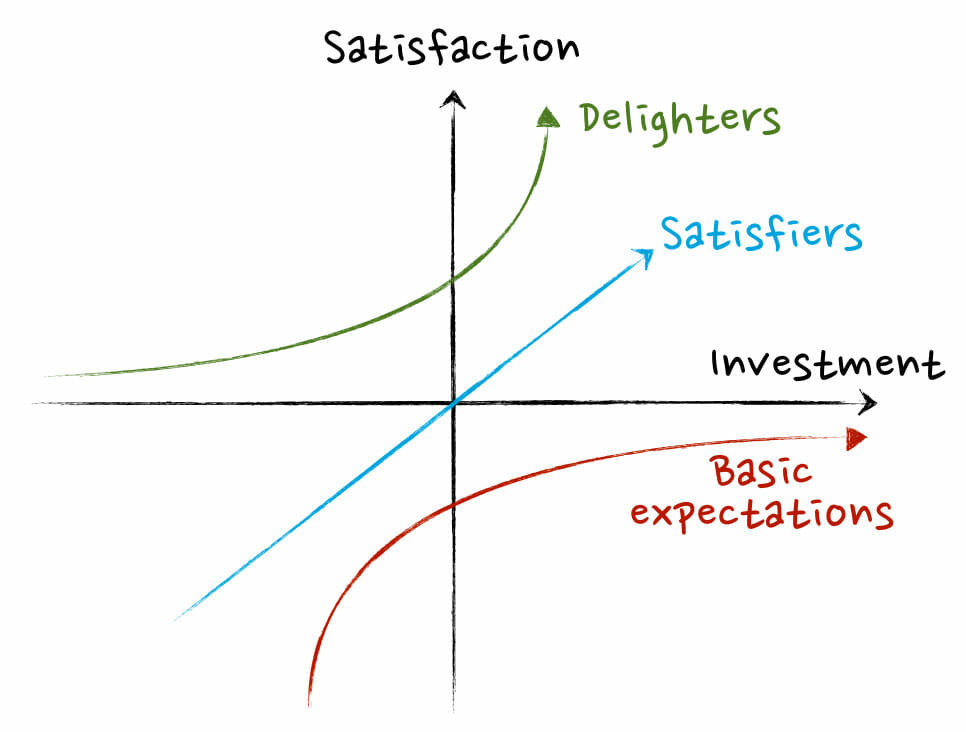

Key Customer Outcome

In this stage, you determine the right customer outcome to focus on, knowing that if you deliver on an outcome your customers care about, your business success will follow. Once you identify the key customer outcome, you can break it down into specific areas of value creation and strategize accordingly. This is your “metric of progress” to know if the product is delivering value to customers. You will go through a similar exercise to identify the key outcome and contributing factors for your business.

Customer Journey Vision

Your customer journey vision is a description of all aspects of the journey a customer will take with your product to achieve their outcomes, from the initial trigger and discovery, where they become aware of your solution, to retention, where they commit long-term. We will provide a number of creative ways of describing this journey, but your goal is to break down the journey into specific steps. It will be far more detailed than a general-purpose mission statement, making the story of how a customer finds, tries, and continues to use your product come to life.

Product Strategy

Once you have a customer outcome and you’ve mapped out the customer journey vision, you need a strategy for getting from point A (today’s customer journey with your product) to point B (realizing the customer journey vision). Your product strategy works backward from your vision and makes it achievable by accounting for business realities and constraints, identifying the key steps along the way, and establishing measurable milestones to ensure you stay on track.

Application of the Framework

When you’ve created a product strategy, you will have completed the final piece of the Vision-Led Product Management framework. Next comes the equally important task of implementing it within your company. To do that, in Part Three of the book, we will show you how to set smart roadmap priorities that feed into the software development life cycle. We will also cover how to hire the best people, establish appropriate processes, and cultivate a strong culture for ultimately realizing your product vision.

Case StudySTORYBLOCKS: THE EFFECTS OF VISION-LED PRODUCT MANAGEMENTStoryblocks is the world’s first stock media subscription service, offering video, audio, and images. We’ve worked with them since 2015 and as their CEO, TJ Leonard, put it, “We can see and feel Prodify’s influence all over Storyblocks.” Over that time frame, the company has more than doubled ARR while growing product and engineering to fifty people, representing nearly half of the Storyblocks team. Over the years, we’ve helped the Storyblocks team with product vision, strategy, and team development initiatives, but there were a couple of moments that stood out. One was an onsite workshop to create a customer outcome pyramid. Prior to that workshop, TJ shared his thoughts with a few people on the three drivers of customer value (plotted nicely on XYZ axes). After the team brainstormed individually how they would draw the customer outcome pyramid, it became clear that there was great alignment within the team. Working across departments, the team came up with a key outcome that revolved around Storyblocks’ aim of “giving all creatives the ability to pursue storytelling without limits.” This served as a great foundation as the team went on to think about products and features that would “10x” the customer outcome by improving the efficiency at which customers could create their high-quality video content at scale. Another example of applying the Vision-Led Product Management framework came from working backward from major milestones to come up with a product strategy. In this case, TJ kicked off the process by providing business outcomes (revenue goals), and we worked with him to draw a strong connection back to the customer value they needed to deliver in order to drive the top-line growth they sought over a five-year horizon. From that point, the product team was able to identify the gaps in the existing product and craft a strategy to fill those gaps to realize their product vision in a way that ensured customer and business outcomes would be aligned in the end. |

ANCILLARY BENEFITS OF AN ASPIRING VISION

Having a compelling end-state customer vision can also do wonders for your company when it comes to hiring, employee retention, and fundraising. People want to work for and invest in a company that has an exciting vision, so if you can show people the amazing things you’re working toward, they are going to be far more interested and engaged in what you’re doing. That’s the hidden power of strong product leadership.

Ben’s Story

A Vision Worth Sharing

When I first met James Quigley, co-founder and CEO of GoCanvas, we talked for a while, and at the end of our discussion, he boldly declared that I would work for him one day. I politely told him I appreciated the sentiment but had no plans to leave the advisory practice I’d started.

For the next two years, I advised GoCanvas on several fronts: team growth and hiring plans, organizational structure, product design, and pricing. It wasn’t until we began working on a customer-centric product vision that I, as an outsider, finally understood the magnitude of the opportunity for GoCanvas. The product already helped mobile workforces digitize their data collection processes (invoices, inspections, timecards, etc.), and the vision answered the question, “How could we help customers grow their businesses, keep employees safer, and improve the experience for their customers by allowing them to do more with the data they are already collecting?”

But it did much more than that. Indeed, the product vision was inspiring enough that GoCanvas became an opportunity I simply couldn’t pass up, and though two and a half years earlier, I wouldn’t have entertained the possibility, I excitedly joined the company in 2018 as their first chief product officer. The same vision contributed to a later investment from the top-tier private equity firm K1 and several excellent senior hires. That’s the magic of a compelling vision grounded in customer value: it turns heads and changes minds. The only downside was having to hear James say, “I told you so,” while introducing me to the company on my first day.

ACTION CHECKLIST AND RESOURCES

Visit buildwhatmattersbook.com for an action checklist, as well as resources about what it means to become product-driven, how to know if your company is product-driven, and details on the key concepts of Vision-Led Product Management.

To continue reading, you can buy Build What Matters on Amazon.

Comments

Join the community

Sign up for free to share your thoughts