Roadmaps can be a powerful tool to communicate the vision for a product’s development, unite teams of makers around common goals and let stakeholders know (roughly) when they can expect the improvements they care about.

That’s why everyone loves a good roadmap.

But getting them right is hard. Roadmaps are born of all sorts of compromises: between committing to a plan while remaining agile; between giving product teams autonomy while aligning their work to business goals; and between improving existing software versus getting new stuff out the door.

This post sets out (in some detail) how we’ve recently built and now maintain a product roadmap for GOV.UK, what’s working about our approach and what’s not, for the benefit of our stakeholders, fellow software teams and fans of agile delivery everywhere.

But first a bit of context: why have a roadmap at all? What, if you’ll forgive the company mantra, is the user need?

"Roads? Where we're going we don't need roads"

Despite development on GOV.UK starting over 2½ years ago, we’re relatively new to the roadmap game.

Early on, there wasn't a compelling need for one. We were in startup mode: a handful of small, relatively independent teams building minimum viable products, with a smallish community of stakeholders sharing the same postcode. Heads down, focused on what was right in front of us, we didn't need roadmaps.

But now the opposite is true. Our team structure and technical architecture are complex and interdependent. We're balancing new features, improvements, bug fixes and repaying technical debt. Our users are everyone, our stakeholders are everywhere and, as a product team, we hold the keys to hundreds of government organisations' main means of communication and service delivery.

Clearly it's important both that we have a plan, and that we explain what it is.

As GOV.UK aged 1-going-on-2 we need a roadmap, so that:

- We can be confident that our limited pool of people are focused on solving the most important problems at all times

- Everyone working on the product knows what each other is doing or planning, and therefore can manage dependencies, collaborate and avoid duplication or rework

- Stakeholders can see what product developments are expected and not expected as far into the future as we can look, and therefore can plan and lobby us accordingly

Step 1 was to design the format and process by which we would collate product development from multiple separate teams into a single view.

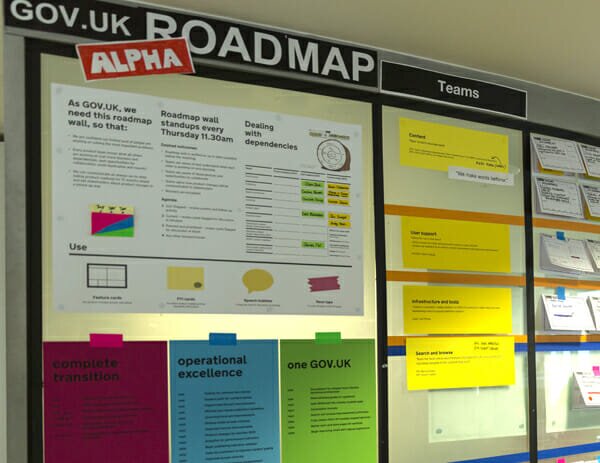

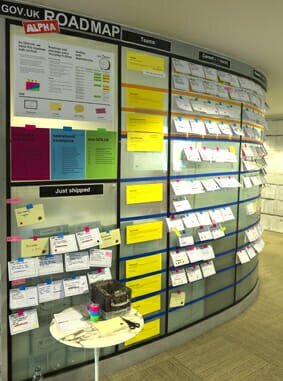

So we built a wall.

"The way I see it, if you're gonna build a time machine into a car, why not do it with some style?"

Like all agile teams, we love a good wall. Walls are brilliant information radiators, and highly effective as a focal point for collaboration.

We've put a lot of design love into the wall we've built for GOV.UK.

Here's a walkthrough of our wall and the thinking behind it, including how we've tried to resolve the compromises I mentioned at the beginning of this post.

1. Swimlanes and mission statements for autonomous teams

Probably the toughest challenge in roadmapping on a large, multi-team product is striking the right balance between (top-down) business goals and (bottom-up) team priorities.

For example: should the roadmap be a single list of features spanning the entire product suite, prioritised relative to one another by a lead product manager? It's tempting to do exactly that but – from experience – this kind of "one backlog to rule them" approach tends to be counter-productive.

Good products are made by good teams. Good teams need space to work, and to have ownership of identifying the problems within their domain and solving them creatively. Dictating priorities and dishing out feature ideas is anathema to that, and highly demotivating. Moreover, multidisciplinary teams, personally invested in what they are doing, are best placed to know what's on fire, what's important and what can wait – not middle managers who are less close to the day-to-day.

And so, running down the left hand side of our wall we have swimlanes for each team, with a formalised mission statement which gives broad direction and boundaries to a problem space they own. Teams have autonomy to prioritise and solve problems according to their respective missions.

Those missions, and consequently team structures, can and probably will need to change over time (see below) – but not without good reason and not overnight.

(I’m massively indebted to Spotify for this video about the engineering culture they aspire to, which helped shape my thinking in the right way about this stuff).

2. Carefully worded column headings for time periods

So, like other wise roadmappers, we're careful in the language we choose when we talk about time. We even picked a curved glass partition in our office to use as the roadmap wall so that the future is out of view – we literally can't see what's around the corner.

Our column headings are:

- Just shipped – we keep a month's worth of done features as a prompt to make sure we've communicated about them and validated that they solved the problems we thought they would, through research and analytics (it also makes us feel good to see a growing pile of done cards)

- Current – doing/planned for this sprint and the next – this column is relatively reliable: teams can speak with some confidence about a month's worth of work

- Planned – under consideration for 3-6 sprints away – these features are being considered, not confirmed

- Prioritised – tentatively queued for discovery/detailed planning – a queue of cards we think we might get to in around 3-6 months, in approximate priority order

For this last column, the team swimlanes disappear and the features merge into a single list. This gives us flexibility to re-think teams and missions if the shape of the work 6 months down the track doesn't match the way we've currently organised ourselves.

3. Information-rich feature cards

The currency of the roadmap wall is features, where a feature is defined as a chunky thing which someone cares about, equivalent to anything from 1 to a dozen user stories.

We find that this level of detail is just right to show our diverse stakeholders the things they variously care about and to tease out the dependencies between our teams.

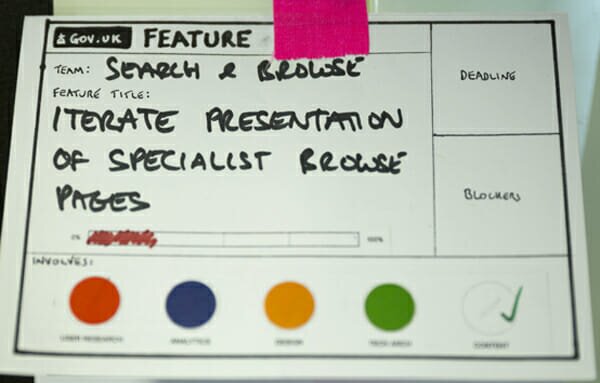

To represent each feature, we use this bespoke feature card template.

Our feature cards are the heart of the working wall, designed to communicate progress, manage dependencies and highlight blockers. Cards on a roadmap wall tend to hang around in one place for a while (compared to Kanban, say) so we used the design of the cards themselves to be active.

On the card are spaces for:

Title – card titles are expressed as a problem or outcome, if the detail is not yet known, or as a proposed solution if it is. (Hence, cards in the current column tend to be titled as features, whereas cards further to the right describe problems).

Progress bar – this is a rough guide to how "done" the feature is (or “solved” the problem is), which is entirely down to the product manager's Spidey-sense and can go down as well as up, for example if unforeseen complexities are uncovered.

Blockers – we stick a note here to flag if there's a problem that needs clearing.

Deadline – we stick a note here to alert us to any real, immovable deadlines.

Dependencies – here, we use coloured stickers to highlight which features have need of input from disciplines outside of (or virtually assigned to) the product teams, namely:

- User research

- Analytics

- Design

- Technical architecture and infrastructure

- Content design

Coloured dots are easy to spot from a distance, so people can track where their input is needed.

Comms – there's an additional sticker space to flag features which require careful communication to end users or stakeholders, so we remember to make that happen at appropriate times as the feature progresses.

The cards are printed on A5, folded in two. Inside, there is space for more information – typically a description of the user need, notes on scope and definition of done, plus some checklists to remind us to consider all the dependencies carefully. (Checklists FTW!)

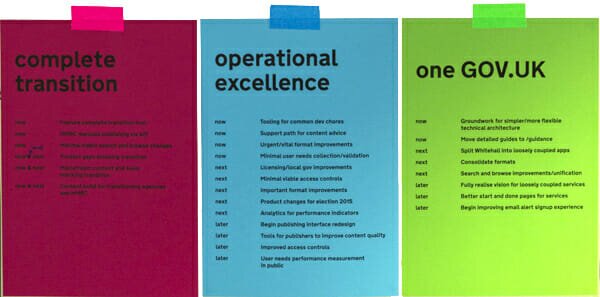

4. Colour coded business goals and objectives

The final part of the roadmap puzzle is how to provide a view of why these features are being prioritised, and a way of zooming out from the detail to see the bigger picture.

We're doing this using colour-coding. (Hat-tip to FutureLearn whose colour-coded roadmap inspired us to do something similar).

These 3 neon coloured posters show the 3 strategic goals from our business plan.

Under each goal we list the epic-level objectives, in the order in which we currently expect to tackle them (which the teams have worked together to agree), labeled as:

• now (roughly equivalent to the current quarter)

• next (roughly 4-6 months away, depending on how long the ‘now’ stuff takes)

• later (7+ months away, at a guess)

To cross-refer our features up to these goals and objectives, we combine form and function using matching neon tape to stick the feature cards the wall.

A quick glance at the coloured tape on the wall reveals the spread of features in support of each goal, and how that changes over time.

And while teams take the lead on identifying priorities within their missions, the coloured tape also acts as a constraint to make sure features always relate back to business goals (if it doesn't support a goal, there's no tape to stick it up with!)

5. "About the wall" poster

Last but not least, in the top left corner we’ve devoted space to an explanatory poster, radiating information about the wall itself in a satisfyingly meta fashion.

It might seem too trivial to mention here, but actually it serves 3 important functions. It:

- enables visitors, new team members and other parts of our business to understand what they're looking at and why it matters

- reminds us of the purpose and agenda for our weekly roadmap meetings

- names single points of contact for resolving dependencies across shared functions (the people who keep tabs on the coloured dots on feature cards, and need to be consulted as those features progress)

"If my calculations are correct, when this baby hits 88 miles per hour, you're gonna see some serious $h1t"

After a couple of months and some iteration to get it to this point, our roadmap wall is undoubtedly helping us accelerate in a straight line to where we want to go. (The future, Marty!)

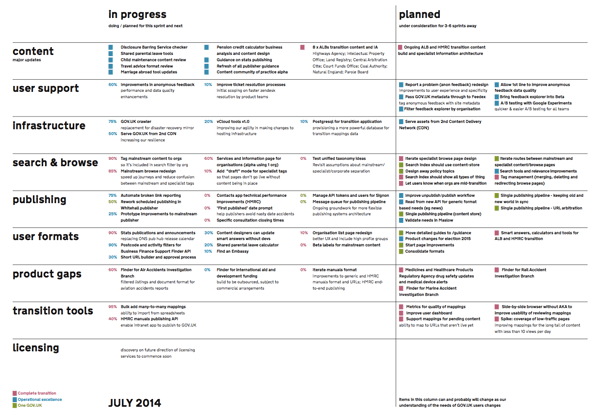

But what about our stakeholders? You can't very well take a wall to boardroom-style stakeholder meetings or send it out by email to the British Embassy in Kabul.

So in addition to the wall (and despite our digital by default mission), we update and issue a paper handout version in advance of monthly cross-government stakeholder meetings, so attendees can pore over it and bring annotated copies to the group discussion.

Here's how the handout version looks:

Download the PDF for a proper read. Again, note the carefully worded caveats about dates and change.

We’ll probably digitise it sometime, when we’ve tested the format a bit more, but will keep the idea of issuing it monthly. Sending it out with a monthly datestamp further emphasises the degree to which things can change. The roadmap document at any given time is only what we know this month, and next month it may look different again.

"Having information about the future can be extremely dangerous. Even if your intentions are good, it can backfire drastically!"

So what's not working quite so well?

Three things spring to mind.

- Communicating meaning through feature titles – describing product changes in just a few words with no pictures, and having that make sense to makers and stakeholders, is fraught with difficulty. We've had a few panicked phone calls from stakeholders, which invariably come down to misunderstandings about what the words actually mean.

- Representing "business as usual" – the roadmap belies the enormous amount of effort our teams are putting in to reactive and unplanned work: the daily business of operating the world's largest government website and a huge, distributed publishing operation, none of which the roadmap includes. (I’m fairly convinced it shouldn’t).

- Really managing expectations about dates – no matter how many disclaimers and how careful with words we are, there will always be stakeholders who want to hold us to a date. I think we (and maybe all agile teams) can get better at balancing stakeholders' need for certainty with our need for learning by doing. But that's a subject for another blog post, and I've detained you long enough.

"Go forth time travellers, and remember the future is what you make it!"

Phew – thanks for making it this far. I hope it's been of some use. I'd love to know what you think, and especially to hear from other product teams about how you map yours.

[Tweet "Interesting read about roadmapping at gov.uk "]