I’m sure you’ve heard about strategic or value-based pricing, where price is determined according to the value it creates for the customer. It sounds great; we all want to avoid overpricing or underpricing our product and any subsequent revenue loss, but how do we do it?

I’m a product coach at Founders Factory. We’ve found that product pricing is one of the most challenging areas for the founders we work with. We designed a pricing workshop to help them tackle pricing challenges, and it’s become so popular that I thought it would be worth sharing with the Mind the Product community. My aim is to give you some practical tips that you can use to come up with the right pricing structure for your product.

This fascinating topic is often overlooked, but it’s key that we, as product managers, create viable products. We focus on creating a product that solves a frequent or big-enough problem, provides a great customer experience, and evolves as the customer needs change over time. We do this in a very iterative way: continuously learning and changing according to those learnings. But for some reason, we don’t have the same mindset when it comes to pricing. Prices are determined based on some old-school techniques such as cost-plus pricing or competitive pricing, by someone who has been working in isolation, not close to the product or customers, to come up with the pricing structure.

I strongly believe that pricing deserves the same treatment as any other product decisions. First, you need to gather data and conduct relevant research before coming up with a potential pricing structure. Keep in mind that it’s unrealistic to think you will get it right the first time (I strongly encourage testing and iterating), and it’s not a one-person job. It should be a team effort. Everyone in your team has different insights into your product and customer needs, so don’t let that information get lost.

Here is a 7-step guide that we developed at Founders Factory to help our startups come up with the right price.

1. Metrics you report on – North Star Metric

A good starting point could be to look at your North Star Metric (NSM). If you have not yet decided on your North Start Metric, you should collect all the metrics you use to see how well your product is doing. It is always good to sense-check your pricing structure to see whether you are optimising for your North Star Metric. For example, it can translate into completely different price levels – as well as product development focus – when you optimise for revenue instead of the number of active customers.

TIP: Your North Star Metric should be reflective of your business model. For example, if you work in an enterprise business, your North Star Metric is likely to be total contract value or revenue. If you're in a subscription business, your North Star Metric is probably monthly recurring revenue (MRR) while if you are a transactional business, you would probably choose transaction volume or net revenue as your North Star Metric.

2. Customer segments and value drivers

Your customers love your product. That's great! Can you tell me why?

All markets are made up of segments, where consumers are willing to pay varying amounts depending on the psychological value they associate with your product. It is key that you identify the segments based on commonalities and purchasing behaviour – for the simple reason that your company will lose money unless there are prices tailored to each of these segments.

After identifying the segments, you should identify the values that drive purchasing decisions within segments. Value drivers will help you understand what features you need to base your pricing on.

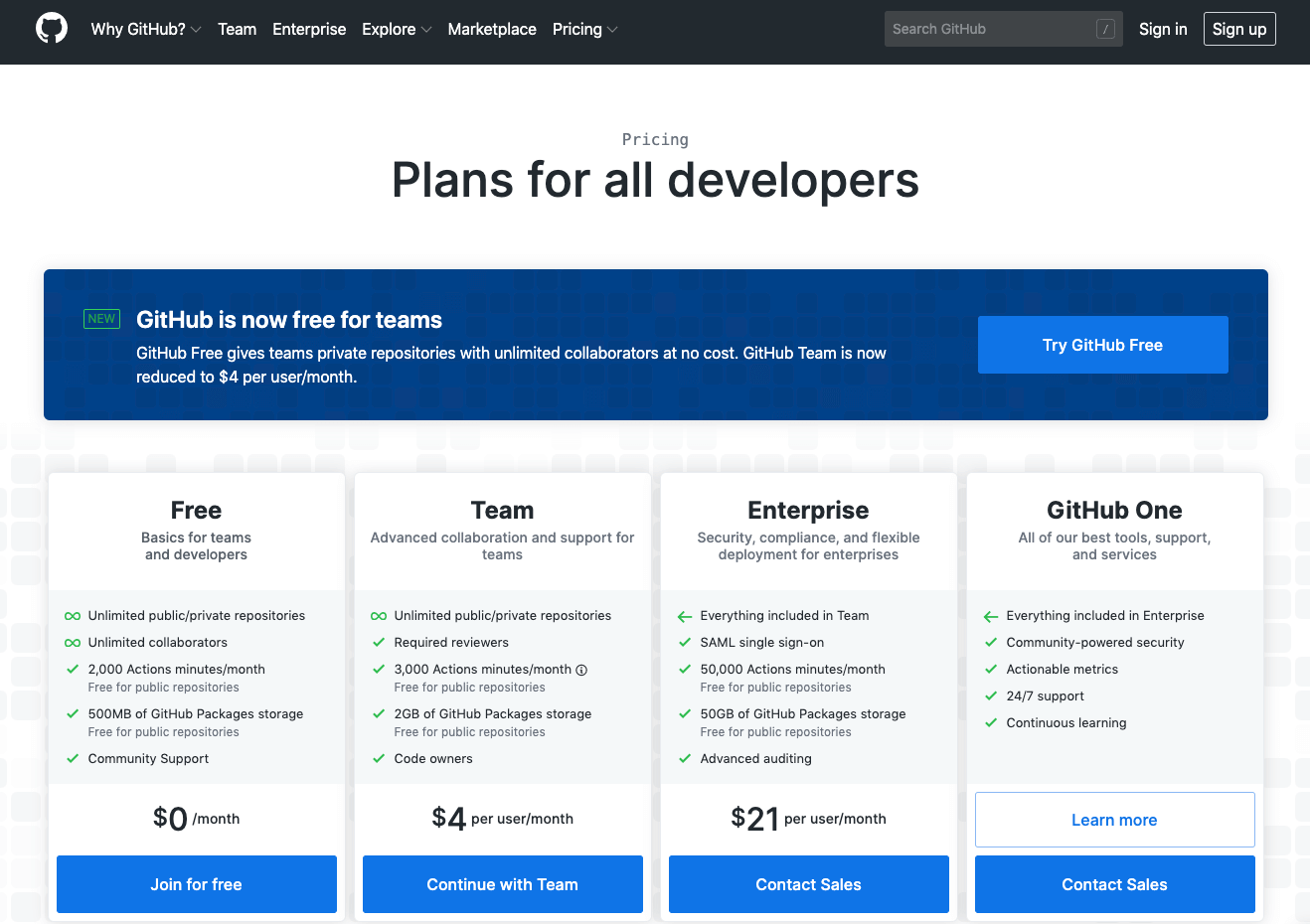

Take Github’s pricing (at the time of publishing) as an example. Here you can see that"code owners" is not listed in the free package, which is suitable for one developer or very small teams. This is because a team of three can probably oversee who has control over the different parts of the code, and that is why it's not necessarily a value driver of individuals or very small teams. But, for slightly bigger teams, it becomes really important to assign ownership of certain parts of the code to certain people.

This way, the right people review the changes and spot more mistakes, ensuring better quality. So, even though it is free for teams to use Github, teams who need better code management and more control over contributors (value driver) will be more likely to choose the team package so that they have “code owners” (feature).

To come up with the right value drivers, you need to do some research and gather and analyse behavioural data on your customers. Try to answer the following questions:

- Who are your customers?

- Why do they use your product?

- Which features do they use? And how often?

- Can you come up with user segments based on their behavioural data?

- What could be the potential value drivers of those segments?

When answering these questions, you need to dig deep. Once, when I was working with a company to help restructure its pricing, we realised that we were giving the most important value driver away for free. Its app operates in the education sector, and it simulates real-life scenarios to prepare students for exams and jobs. Random scenarios were available for free and specialisations (that followed the curriculum) were behind the payroll. The reasoning behind this was that it was more valuable for the students (target audience) to pick a particular specialisation to prepare for a specific exam. However, data showed that random scenarios were also used a lot more by premium users (in the free package that was the only option). So the product’s real value – that got users addicted – was not knowing what to expect. Just by factoring in this information we significantly increased the number of paying customers.

TIP: Have you asked your customer success/marketing/sales team about what they think about the value the product creates? They usually have great insights and quotes from customers, so you should leverage that. Per-user pricing only makes sense if there are differentiators in the product.

3. Competitors and Costs

Neither your costs nor your competitors should be the main drivers of your pricing decisions. But they can be important things to factor in.

Competitors: The total economic value of your product should reflect the value of the next best competitor plus the value of the differentiation between your products. The key here is to know how you are different from them and build that into your pricing strategy.

One of our portfolio companies competes in a really crowded market, so it was extremely important to be super clear about why it costs more than its competitors. Sometimes you simply have a better solution than anyone else, but it may be something else. In this case, the additional value is that the service uses niche segments of the unemployed, making it much more attractive to a certain customer base.

Cost: Again, it shouldn’t be the key driver of setting the price – consumers don’t care about your cost – but naturally it’s an important consideration. Think about both fixed and variable (a cost that varies with the level of output) costs!

TIP: If there is no direct competitor, try to look at something similar in the sector.

4. Pricing Structure

Here I'll provide an example inspired by the book The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing.

Consider a market with three segments: one with a sales potential of 100 units where customers are willing to pay £10 per unit; another segment with 150 units where customers are willing to pay £15 per unit; and the third segment with 110 units and customers willing to pay £20 per unit.

A supplier might look at these numbers and decide that by pricing in the middle of the range, at £15, they would earn the most. But how true is this? By setting the price at £15, customers only willing to pay £10 will be disappointed and unwilling to buy, while those willing to pay £20 are taking an extra £5 home with them – money that could easily have gone into profits. So what’s the solution? Instead of offering a single price, you can segment the market by creating different packages suited to each target group.

I would advise you to start the package creation by determining an initial price window with a ceiling and a floor for each package. This window outlines the highest and lowest acceptable prices for a product as defined by its total economic value. It will help you to play around with some scenarios.

With one of our portfolio companies, we quickly realised there are two significantly different user types: individuals and teams. However, individuals can drive team subscriptions so we designed the pricing to support that. We came up with four packages: two designed for individuals (free, premium), two designed for teams (one team, more teams). And we defined the price level of the individual premium package very close to the price level of the one-team package per user amount, in order to encourage individuals to invite their teams to the platform.

TIP: Localisation correlates with more growth, think about localisation.

TIP: Make it easier for your customers to figure out what package is the best for them. Don’t have more than four options so they don’t get decision paralysis.

5. Fundraising Story

Again the fundraising story should not be the driver of your pricing, but it is important to check how your pricing structure will affect your financial model and plans.

TIP: Make sure you collect the feedback/questions of each investor discussion as they can be really helpful.

6. Communication Strategy

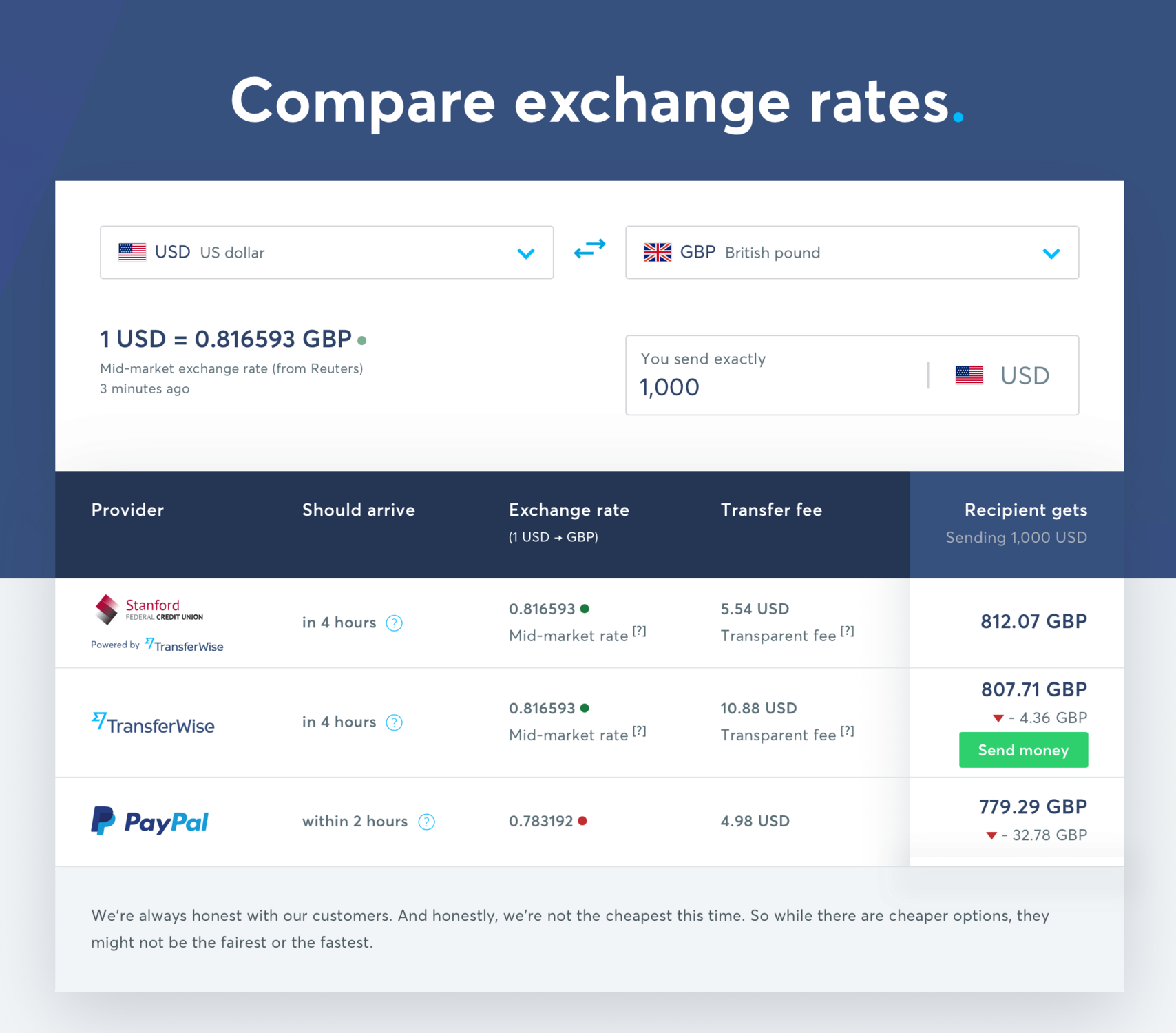

Think about how much effort you put into researching products you want to buy. People often get frustrated if they have to read through several long lists of specs, so why not make it easier for them? Transferwise earned so much trust by not only being transparent about its prices but by also making it easy for customers to compare its rates with those of competitors. If Transferwise isn’t the best choice at that particular time, it will tell you which provider is. So even when it doesn’t provide the best rates, it keeps earning the trust of its users.

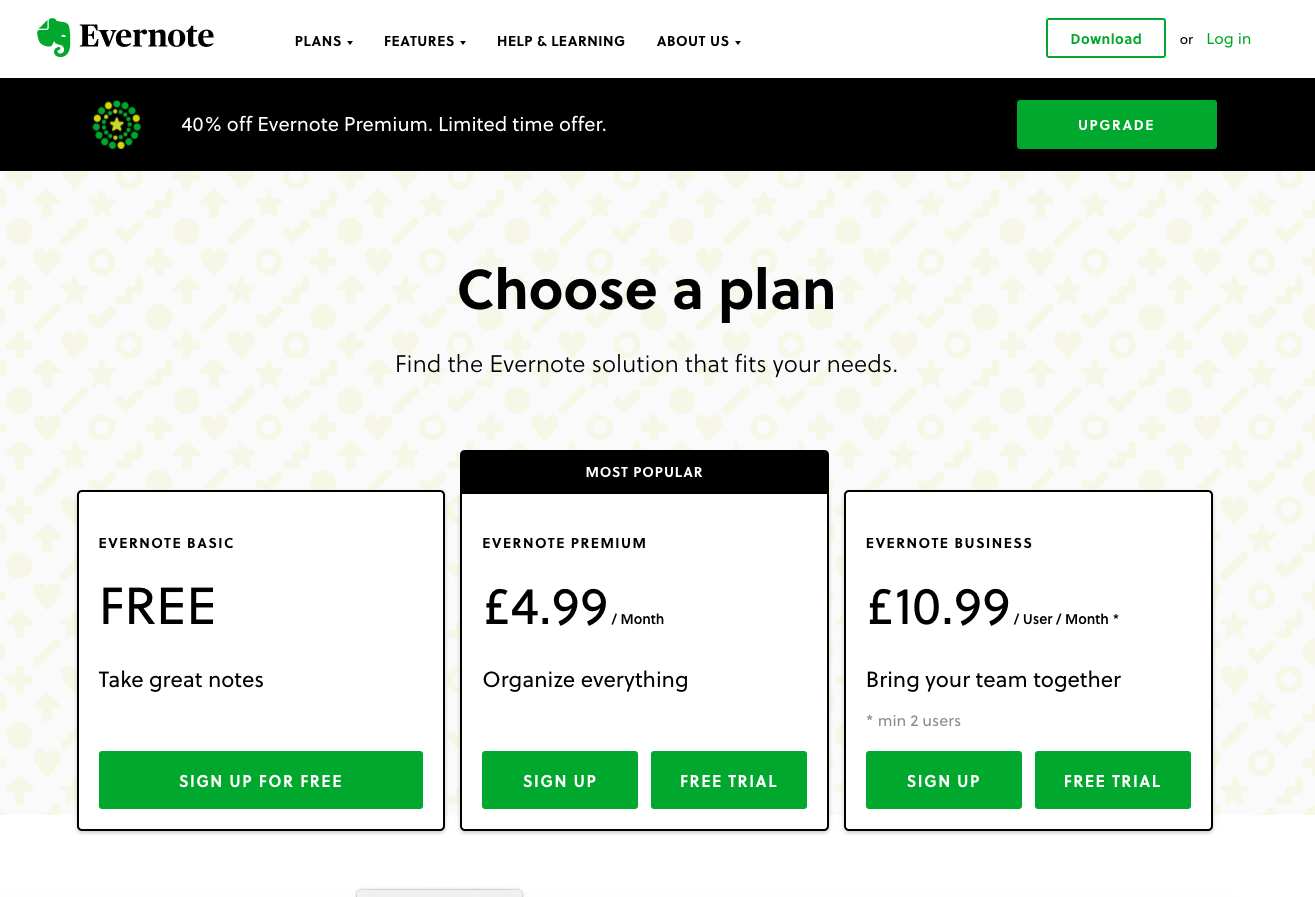

You should always keep your communication simple, clear and transparent, and if you can, make the cost of research minimal. Help your customers understand why your product is a cut above the competition. If your product is the priciest among the competition make sure the reason why it’s worth more stands out. Don’t underestimate the power of an honest explanation! It is also crucial to communicate outcomes rather than focusing on the features of your product. How will your product change the life of your customers? They don’t care about long specs, what they care about is the impact of your product. A good example of this is how Evernote communicates outcomes such as 'Take great notes', 'Organize everything', and 'Bring your team together' in its packages, as shown here:

TIP: Freemium can’t be a crappy version of your product.

7. Test

As I said at the start it’s unrealistic to think you will get it right for the first time. Don’t be afraid of experiments and changes. If you are transparent about your changes, people will understand. Even if you lose some customers you may end up with bigger revenues.

As a B2C company, you can run ad test / landing page tests to figure out the right price level for your target audience. One of our portfolio companies simulated different cost calculations to understand the margins it would make at different price points. This gave the product floor price – the lowest it could go to ensure break even in a reasonable time frame. Looking at competitors' pricing gave a price ceiling. The company then ran a few Facebook ads and corresponding landing page variations to determine which price level would work best. Surprisingly (or maybe not so surprisingly) it was not the cheapest option that prompted most of the sign-ups, demonstrating that your price should reflect the psychological value of your product/service. Sometimes things seem to be “too cheap to be true”.

In B2B every sales pitch could be potentially used as a way to test prices. You can ask questions about your customer budget, or if that is too sensitive, you can always ask about other products they bought to get a sense of the budget.

TIP: Whenever you test prices avoid hypothetical questions like how much would you pay for something. That will not give you reliable answers.

Happy Pricing!

I hope this helps you to get off to a good start and, before you do, remember to keep in mind a couple of things – you'll not get it 100% right the first time around, and it’s not as big a deal to change prices as you might think, people are used to changing prices. The key is to be transparent about the reasons for the change.

In the meantime, if you have any questions, feel free to reach out to me.

Happy pricing!

With thanks to my colleagues Ollie Haskins and Kartik Krishnan for the brilliant minds and support.