How do you set your subscription pricing? You might look at your competitors' pricing structure and set yours similarly. Alternatively, you may work out your costs and add a little margin. Finally, you could be just relying on your intuition. All these approaches can work — but all of them also can leave a lot of your money on the table. You already may have read a lot that the most profitable pricing strategies put customer value front and center, and that they should be driven by data, and match your customers' purchasing and usage habits. Certainly, right pricing – especially for subscription products – is not pulled out of thin air. Pricing is hard, and in this article I will outline a few common strategies and models for setting your pricing, and give a few practical advice on what to consider to get your price just right.

What is subscription pricing?

In the subscription-based pricing model, customers pay regularly for a service or product, most commonly a monthly fee. Subscription pricing is different from pricing for traditional products, as pricing is often based on the subscription length, making longer subscriptions the cheapest option.

Infrequency – one thing almost any company get wrong about subscription pricing

The amount you charge for products or services should be taken seriously, yet many businesses do not take the time to consider this properly. Many companies with a subscription business model may spend less than ten hours each year on their pricing. This happens for several reasons, such as pressure to acquire new customers instead of optimizing the value of those they already have, a lack of knowledge on how to price, failure to invest in collecting customer data, and many more.

However, even if you spend double that amount of time on your pricing strategy, if you're not also avoiding the following one mistake, you could be charging less than you should.

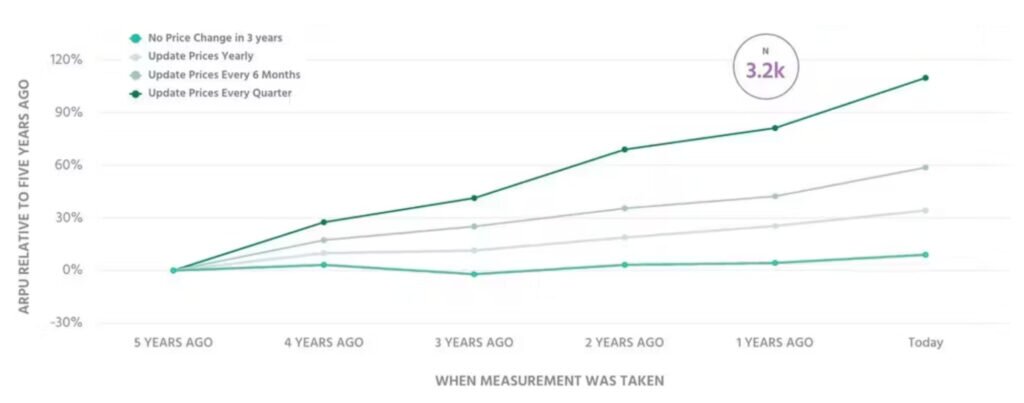

The most common mistake almost all companies make when working on pricing is that they update their pricing infrequently. The study from Profit Well, a US-based subscription revenue optimization platform, proved that companies performing regular price changes are seeing much higher ARPU growth relative to their ARPU five years ago.

Out of 3,200 companies analyzed, those which have not changed the price in the last 3 years have not demonstrated any ARPU growth and in a contrast those who change price every 6 months or at least yearly demonstrated ARPU growth of +30% and +60% respectively (see chart below).

Figure 1. Price changes correlation with ARPU

Source: “Why you should change your pricing every 6 months” by Profit Well

Here are 2 simple reasons why companies that change prices more often have a higher ARPU:

- Price points that work well in the early days of your subscription business often end up underpricing your product over time. As your product or service changes with time, typically it means that the value you provide for your customers also increases over time. So with time you naturally go upmarket as you build more valuable and more complex products that add features that are in demand from larger and more various user segments.

- As your team is looking for the ideal price point, it gets deeper into the experimentation mindset, which will inevitably bring you to a more balanced price, allowing you to leave less money on the table. When you are just starting you might just guess or at best look at competitors' pricing strategies. But the more you experiment with prices, the more you begin to quantify your ideal customers and understand what they truly value in your product and what they're willing to pay for it.

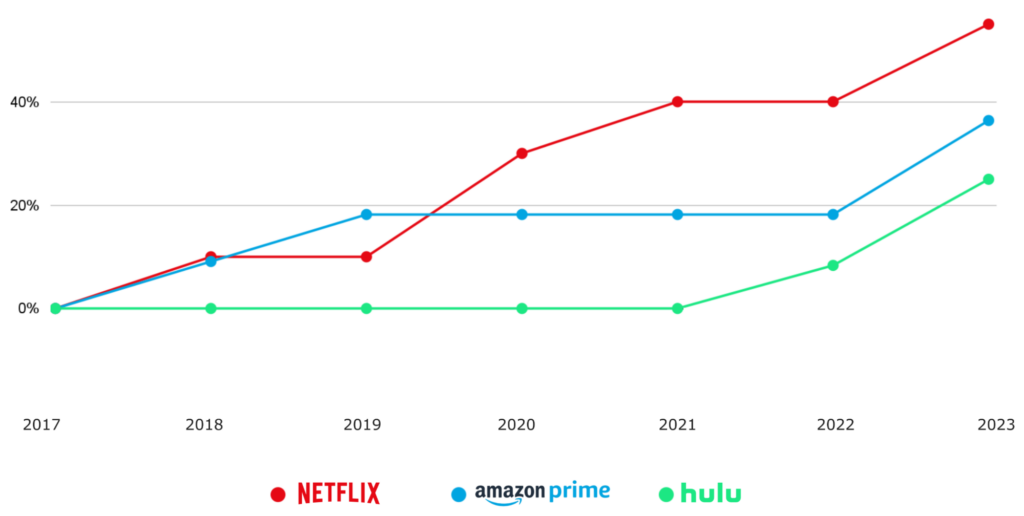

A visible illustration of frequent pricing changes is streaming. All streaming services are getting a little more expensive all the time. Netflix has raised the cost of its subscription multiple times since its launch, so did other major services.

Figure 2. Price changes of selected streaming services in the US (2017 – 2023, indexed)

4 most common types of subscription pricing models

The four common subscription pricing examples for subscription companies are fixed rate, tiered, per-user, and usage-based. Each pricing model works best in different situations and scales according to different factors. Choosing the right model can make or break your profit margin.

1. Per-user pricing model

This model is the most commonly used with software and B2B products and services. According to the research done by Matrix Partners in collaboration with KeyBank, per-user pricing (also called per-seat or per-unit) is the go-to subscription business model for the majority of companies. The researchers surveyed 385 private B2B software companies working in the United States and 39% named “Seats” as their primary pricing metric.

In per-user pricing, price scales evenly along with the number of users – the more users, the more you charge, so the pricing scales proportionally as the number of users grows. Per-user pricing is best for frequently used products that may require collaboration or teamwork but limited to only a few users.

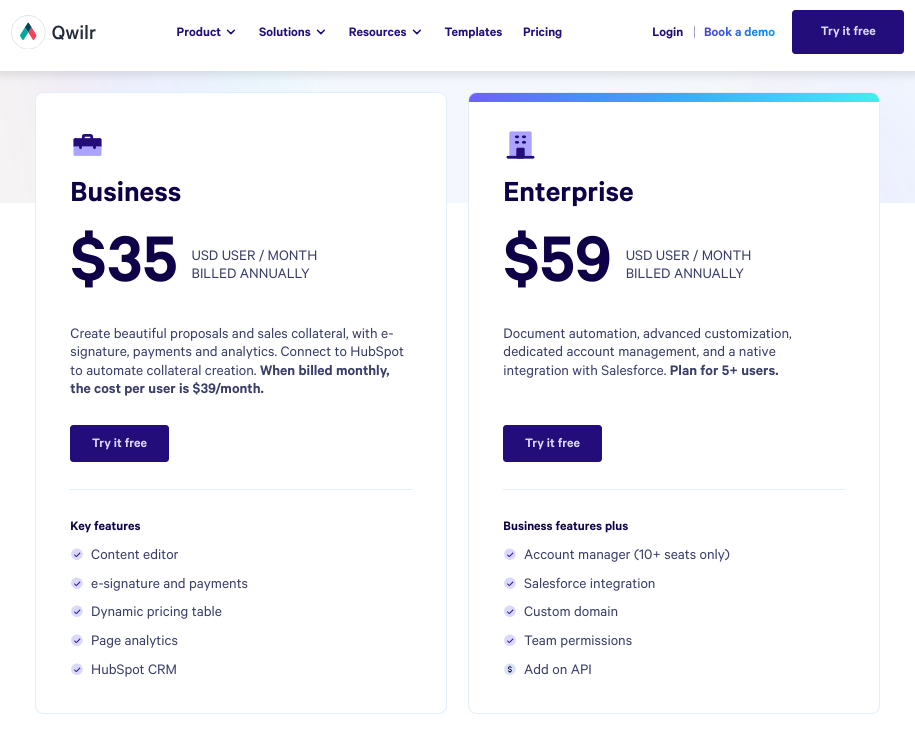

Qwilr makes business software that allows users to create sales and business proposals easily. Its pricing model is simple: $35 per user per month for businesses.

Figure 3. Qwirl per-user model offers convenience for customers that may not need enterprise-level pricing.

Source: Qwilr

Per-user pricing is easy for potential buyers to understand, simplifying the sales process. It also makes forecasting monthly recurring revenue (MRR) straightforward since revenue scales in direct proportion to the number of users.

Per-user pricing is best for frequently used products that may require collaboration or teamwork but limited to only a few users, but it does have downsides, though. For example, if hundreds of people need to use the software, the per-user model is not cost-effective for customers. Also charging per seat can lead to users sharing logins across teams, cutting into your potential revenue.

2. Usage based pricing model

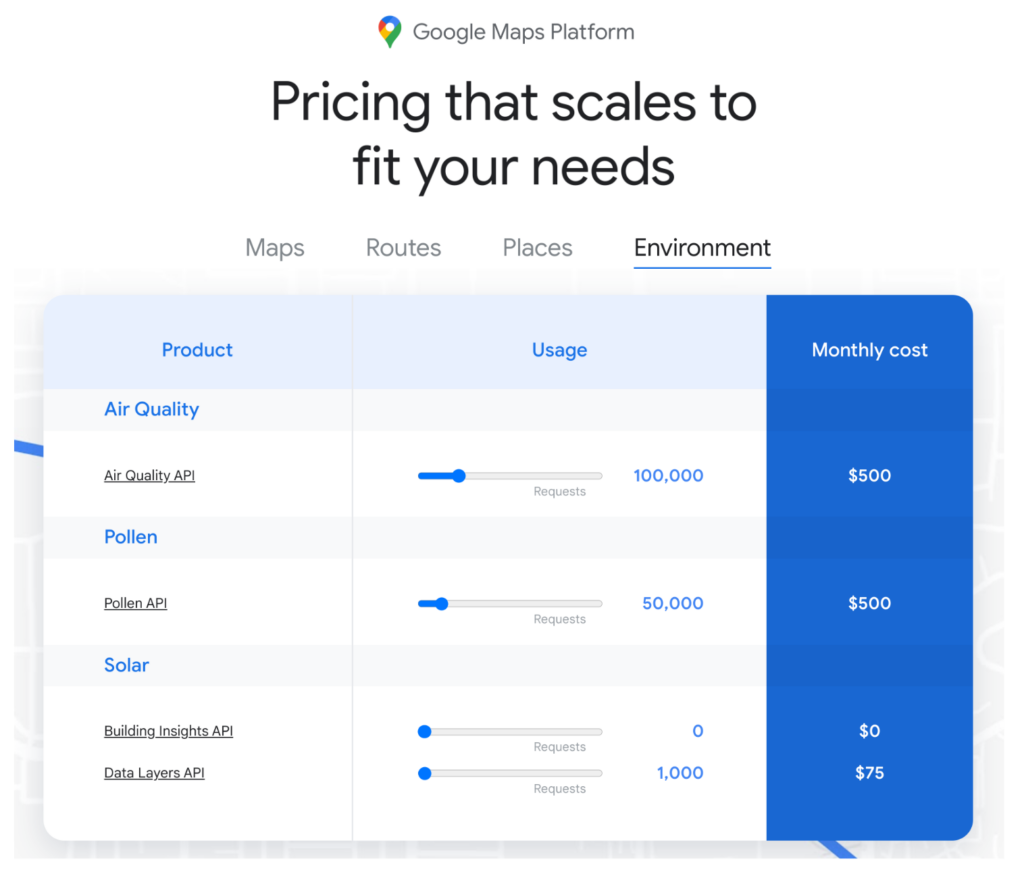

Usage-based pricing model, sometimes called pay-as-you-go, is somewhat less common among digital and software businesses – it's mainly used by telecommunications companies and IT services. Users are charged based on how much of a product or service they consume: for example Google Maps Platform priced their services based on API calls per month: submit 100,000 requests to Air Quality API, for example, and you'll be charged for exactly this 100,000 calls.

Figure 4. Google Maps Platform charges based on the number of API requests each month.

Source: Google Maps Platform

Tying pricing to usage makes it easier for small companies to get started with your product while avoiding the high upfront monthly or yearly fees charged by some subscription companies. On the other end of the scale, it also accounts for additional costs incurred by heavy users, charging them fairly based on the extra time and resources they consume. Charging based on usage does, however, make it much harder to predict revenue since billing can vary dramatically each month.

3. Tiered pricing model

Tiered pricing allows companies to offer multiple packages with different features and product combinations available at different price points. The number of packages can vary, but most subscription companies offer two or three pricing tiers. This is a great model for software or streaming companies that want to offer their customers flexibility.

For example, the most known company which works on a tiered pricing model is Netflix. It offers customers several options when signing up for its services and depending on the country this generally offers various prices based on the number of devices you are going to watch the service.

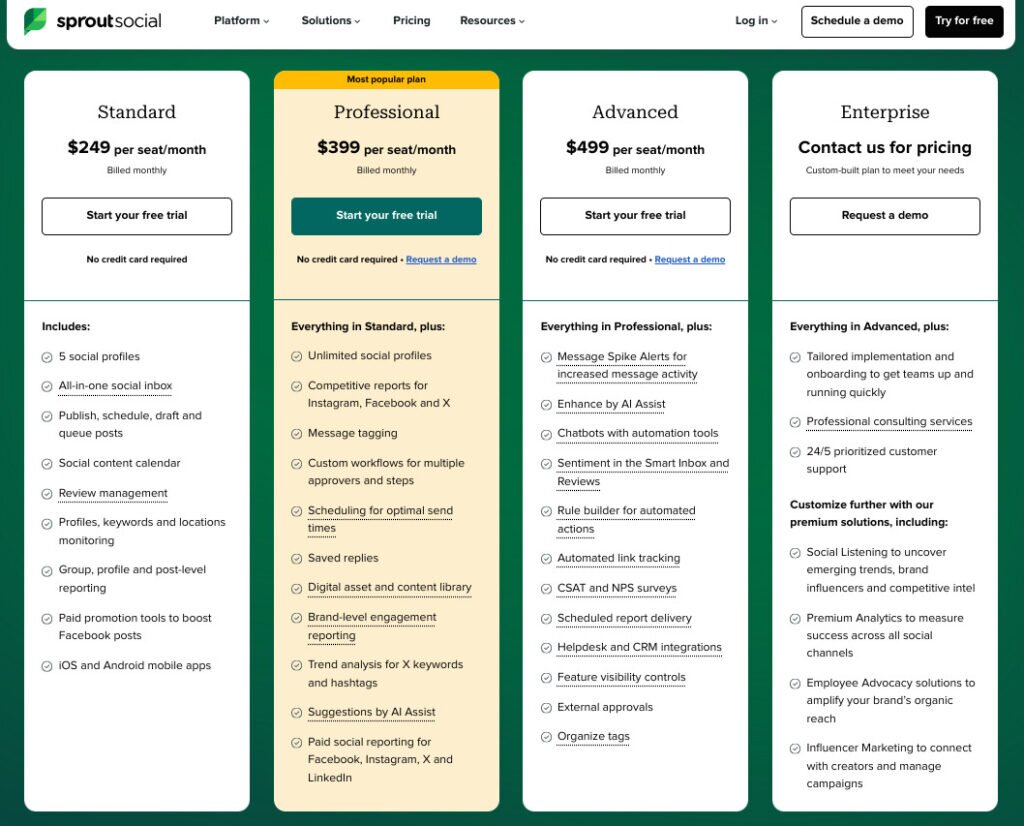

Another great example is Sprout Social, a U.S.-based social media management platform. Company designs its tiers around the needs of different customers, whether they're professionals who need "essential tools" or companies looking for advanced tools "at scale."

Figure 5. Sprout Social's tiered pricing model offers different combinations of features across their three packages.

Source: Sprout Social

By catering to multiple buyer personas at multiple price points, Sprout Social can maximize how much revenue they can extract from each customer while providing an easy upsell opportunity for long-term users as companies outgrow each tier.

Beyond two or three options, however, things start to go downhill – offering too many choices leads to indecision and lower sales. It's easy to try appealing to customer types with varying budgets by adding more tiers, but this leads to 'analysis paralysis' and lost sales.

4. Fixed-rate pricing model

Fixed-rate pricing is also sometimes called flat-rate and it stays simple: a single product, a fixed set of features, and the company charges the customer a regular fee for the product or service. Amazon Prime is probably one of the most well-known examples of flat-rate pricing for subscriptions. The fee doesn't change no matter how much or how little the customer uses the subscription benefits.

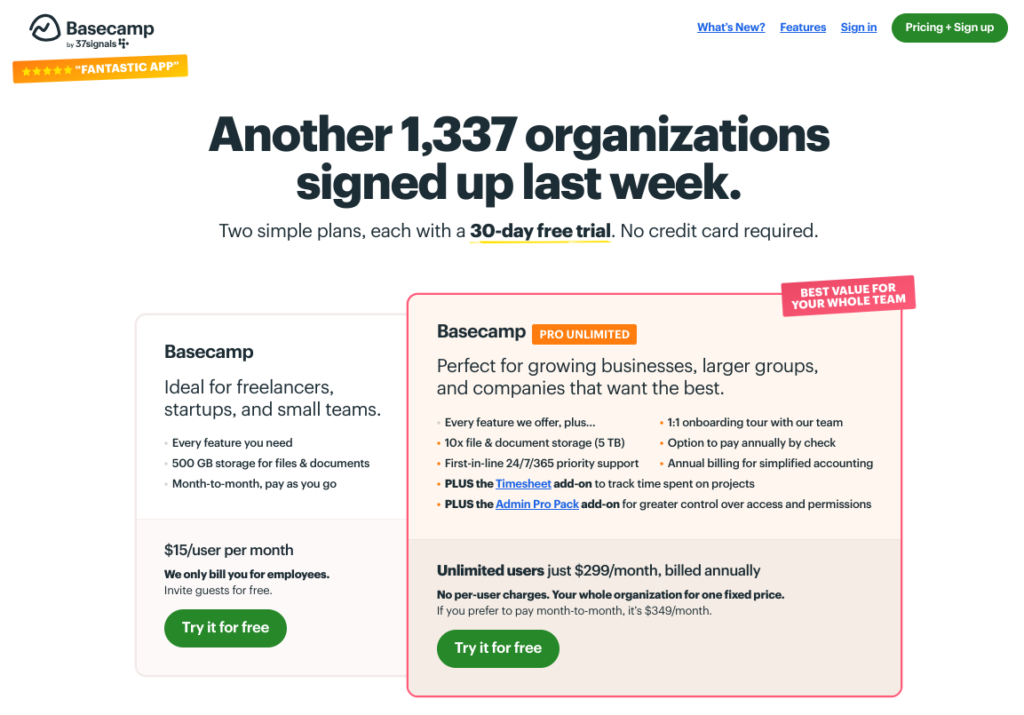

A great example of fixed-rate pricing is Basecamp, a web-based project management software company from Chicago. Company’s product has no tiers and is offered with a flat-rate pricing disregard any usage frequency and without any limitations to number of seats.

Figure 6. Basecamp offers flat-rate pricing on its project management software.

Source: Basecamp

Flat-rate pricing is easier to communicate and easier to sell. If you're adding valuable features, simply raise your rate. If you add additional products, the fixed price goes on top of your base fixed rate. It has been the core of the Dollar Shave Club's initial success, when they offered a simple $1 per month flat rate and this model is being also used by many of the streaming services.

But while flat-rate subscription pricing might be easy for potential customers to understand, it often means leaving money on the table. Keeping prices low means missing out on additional revenue from larger companies and vice-versa; smaller companies might be priced out of higher-cost tools.

Combining several pricing models at the same time

It is also possible to combine several pricing models simultaneously. Let me show you how YouTube combines a tiered pricing model with some elements of per-user and fixed rate pricing.

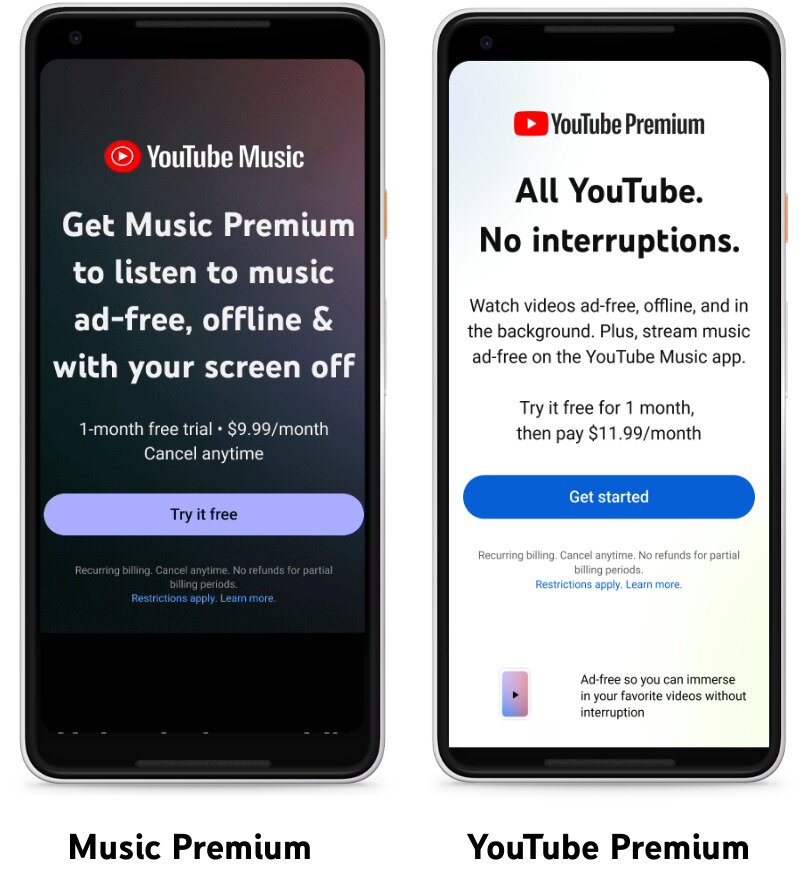

There are two paid subscription services offered by YouTube:

- First one is YouTube Premium, which is a paid subscription which enables ad-free streaming on YouTube, gives access to downloading videos and background playback on mobile devices.

- Second is YouTube Music Premium, which is also a paid subscription, it enables ad-free playback of music content, it also gives the ability to play music content in the background, and the option to download songs for offline listening.

If you look at each of these products individually, you may fairly assume we use a fixed-rate pricing model, as this model is also being used by many of the streaming services. Price stays the same disregarding neither the number of devices you are going to watch the service on nor how many hours of content you are going to consume every day.

Figure 7. YouTube tiered pricing model offers unique combinations of features to different customer segments.

Source: YouTube paid memberships

However, if you look at YouTube’s paid products from a different angle, you may notice that it can be also positioned as two tiers of the same service. YouTube Music Premium is a lower tier and YouTube Premium is a higher tier and being positioned as a flagship SKU, mainly because all benefits of YouTube Music Premium are also available to subscribers of YouTube Premium. From this perspective, you may fairly conclude that YouTube uses the tiered pricing model.

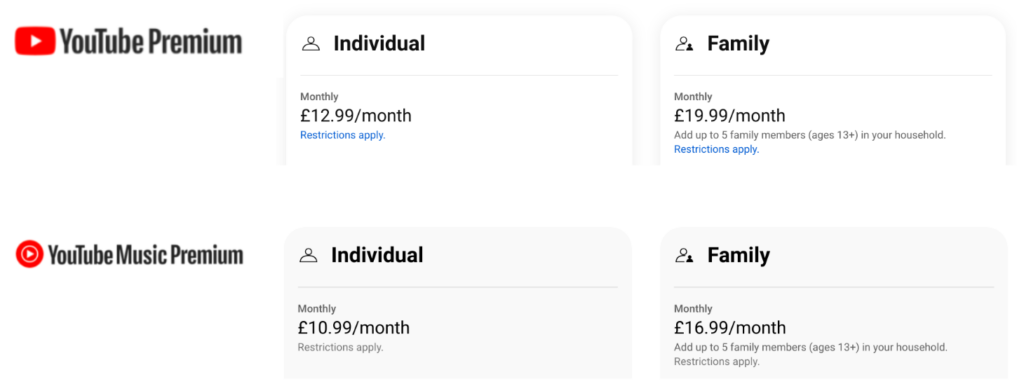

And lastly there are elements of the per-user pricing model which is seen when you compare our Individual plan with the Family plan. Even though we do not make the price to depend on the number of the devices (like Netflix for example), we do scale the price proportionally to the number of users, similarly to Spotify or Apple Music.

Figure 9. YouTube’s per-user pricing model allows it to differentiate between individual and household users.

Source: YouTube paid memberships

What to consider when choosing a pricing model

It goes without saying that different situations call for different pricing models.

First, work out an in-depth understanding of your customer’s profile. Customers who value simplicity might prefer a fixed or tiered pricing scheme over a usage-based one, for example. So the direct route to a successful pricing model is to define your customer segments. These questions may help you to structure your mind around it:

- Are your customers using your product for business or leisure?

- Do they prefer paying up-front or spreading payments over time with a monthly subscription?

- Do they value simplicity or choice when making product decisions?

- How much are your typical customers willing and able to spend on your product?

Understanding your customer segments helps define which pricing model you choose and how much you charge. Match each tier's pricing and feature set to your primary customer segments instead of simply choosing tiers based on which features you want to include.

Second, make sure you do 360-degree regular research about how your competition prices their products. This should never be the only pricing strategy you use, but it's important to know. Two simple things to consider:

- Your competitors are constantly updating and tweaking their own pricing models to match their customers' needs and improve customer relationships.

- Your customers will benchmark your own pricing model against your competitors, but there's no way of knowing the effectiveness of your competitors' chosen model.

Additional tips

1. Go freemium.

Freemium tiers and free trials both give potential buyers a chance to try your product before they buy. But keep in mind the freemium model is an effective customer acquisition tool, but not a revenue methodology, so often they are not suitable for early-stage startups.

2. Give users multiple tiers.

Giving users multiple options when signing up for your product might sound basic, but many companies only offer two tiers: “cheap” and “expensive”. Very often the second tier is useless or expensive and overpowered, and almost by design is not valuable to buyers. If you're using a tiered pricing model, keep users in mind and make sure your offerings match your users' needs, not your own.

3. If your resources are being drained, try a usage model.

It's nearly impossible to predict how many resources each customer will use in any given month. If you discover your resource demands frequently exceed your expectations, try charging based on usage instead. Giving customers the ability to pay only for what they use can help you recover costs easier than increasing pricing across the board.

4. Upsell and cross-sell when needed.

Giving customers the ability to upgrade their accounts as they grow can help grow your customer lifetime value. Look for add-ons that either increase revenue or retention (or both!). Hypothetically, in most cases at least 30% of your customer base would be willing to consider an upgrade. If your customers seem to be hitting a wall in their basic plan, send them a personal email or chat to show them your premium offerings may hold up better.

Price is worth getting it right

The current market environment is characterized by increased competition making customer acquisition costs higher than they ever were before and at the same time struggling to succeed with customer retention and loyalty. Product and marketing teams spend hours in workshops desperately looking on how to improve their product and tweak their positioning.

And in these environments teams tend to spend precious little time thinking about their pricing. But while pricing discussions are often overshadowed by acquisition, higher pricing is one of the most powerful levers for revenue growth, it has a significantly larger impact than improving other areas like acquisition or retention.

But business metrics aside, when you put your end user in the center, your price is the crudest and the most subtle message you can send about your product, so it's worth getting it right.

Disclaimer. The opinions expressed in this publication are solely those of the authors. They neither reflect nor purport to reflect the opinions or views of YouTube, Google, Alphabet Inc., their respective parent companies or affiliates or the companies with which the authors are affiliated and may have been previously disseminated by them. The authors opinions are based upon information they consider reliable, but neither YouTube nor Google, nor Alphabet Inc., nor their affiliates or parent companies, nor the companies with which the authors are affiliated warrant its completeness or accuracy and it should not be relied upon as such.