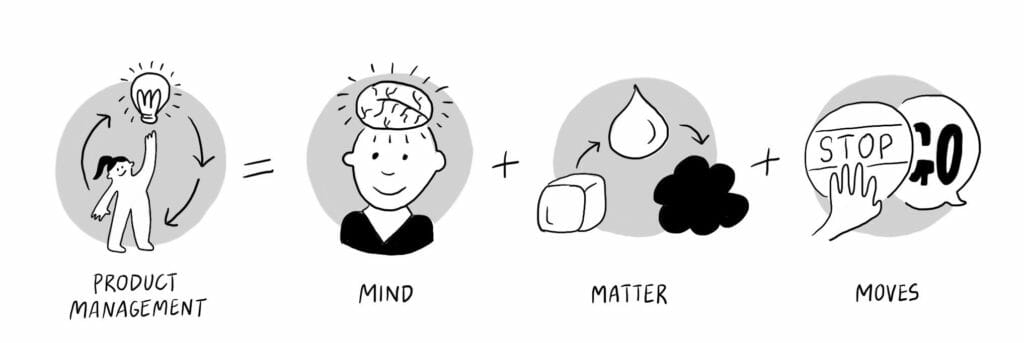

In my book, Managing Product = Managing Tension, I’ve focused on what it is that impacts the products we build and how we manage them, namely; mind, matter, and moves. Each of these factors in their own right creates tension and in the book, I outline how we can make the most of these tensions to create great products.

In my book, Managing Product = Managing Tension, I’ve focused on what it is that impacts the products we build and how we manage them, namely; mind, matter, and moves. Each of these factors in their own right creates tension and in the book, I outline how we can make the most of these tensions to create great products.

To give you a taste, I’m sharing the first chapter with you here and, if you’re a Mind the Product member, you can check out chapters 1 and 5: ‘Managing Product = Managing Tension’ and ‘Leaning into Tension Effectively’. Read Chapters 1 and 5.

If you like what you read, go ahead and buy the book!

Managing Product = Managing Tension

‘Discomfort causes us to think differently, to engage our brains more and in different ways, and this is how we come up with better solutions to problems.’ Shane Snow

In this chapter we will explore:

- How the very nature of product management lends itself to tension.

- The mind of people impacting the product.

- The matter that a product is made of and how it affects development.

- The moves people make in relation to the product.

Introduction

I call it the ‘To Jump or Not’ tension: deciding whether to jump into the pool because everybody else has, even though the water is absolutely freezing, and you really don’t want to go in. It is the situation in which a stakeholder argues that we should be building a feature ‘because the competitor already has it’ whilst the product person is concerned about blindly following the competition without good reason or benefit to the customer. ‘To Jump or Not’ is one of many tensions we can encounter when managing products. I am, for example, thinking back to an experience I had a few years ago where a senior stakeholder brutally interfered with what I thought was a great product plan.

When a senior stakeholder throws a spanner in the works …

I was excited. The new feature that the team and I had planned would drastically simplify the onboarding of new customers onto our platform. Instead of asking people for their personal details early on in the customer journey, we would demonstrate the benefits of our app first and ask for details later. We discussed our assumption that this new feature would drastically reduce the number of people leaving the app as friction would be removed. Happy days!

Then the Chief Marketing Officer interjected … He expressed his concern about missing out on valuable customer data. ‘Despite some customers not signing up, we do get important customer data when they register,’ he explained. ‘This data is then used for our targeted marketing campaigns, and I am concerned that we might well lose this data if we stop asking people to register upfront.’ I was still contemplating the CMO’s words, when he then spoke in a tone that did not leave much room for dissent: ‘So, I have decided that we will stick with the existing onboarding flow.’ You could feel the tension starting to build in the room, with everyone turning to me to see how I would respond …

I paused and said that I understood his concerns but reiterated the need to simplify the onboarding flow for our users in order to create a better experience and increase the number of completed signups. We considered alternative onboarding scenarios which our team had explored and settled on a compromise whereby the first step of the onboarding journey both asked for a limited number of personal details and outlined the app’s benefits.

This is just one of many examples that I have encountered in my career as a product manager; you have a seemingly great creative idea, but an important stakeholder is worried about a potentially negative consequence of that same idea and puts a huge spanner in the works.

Before I became a product manager, I used to be a digital project manager. My primary responsibility as a project manager was to ensure that projects were delivered within budget, time and scope.[1] Highly detailed Gantt charts helped with planning and tracking my projects.[2] Each project would start off hopefully, confident that we would meet the deadlines and dependencies specified in the project plan.

I quickly learned that these project plans are not worth the paper they are written on. As Mike Tyson says, ’everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face’. It would quickly become apparent to me that the technology underpinning the new website was more complex than we had originally accounted for; or the client would not sign off on the new homepage design (never mind that we did deliver it on time, in scope and on budget).

I thus learned the hard way that working on technology never is a linear or predictable process. This is particularly true when we use new technologies in products or when prevailing technologies are applied in untested, novel ways. The very nature of the product management process is highly fluid and unpredictable. The mere fact that you are working with technology drives uncertainty as well as the involvement of multiple cross-disciplined people. As we will see throughout this book, the tension that we experience when managing products is the net result of a variety of ‒ often opposing ‒ causes and effects. Take, for example, the strains we can feel when having to satisfy both the needs of our end users and those of the shareholders of our businesses.

Does that by default make product management more pressured than other professions?! Not necessarily, but the position of a product manager does undoubtedly generate innate tension. When you are covering the commercial, experiential and technical aspects of a product and all the unknowns inherent in any of these areas, it means that you are often flying in the face of uncertainty whilst dealing with highly demanding stakeholders. All these factors combined feed into the highly pressured nature of product management.

Product Management = Mind + Matter + Moves

‘A great product manager has the brain of an engineer, the heart of a designer, and the speech of a diplomat.’ Deep Nishar

Managing products is a bit like an everlasting tug of war, with various forces pulling in lots of different directions at the same time. The three main forces we see are the mind of the people involved with the product, the matter that the product is made of and the moves that people make in relation to the product.

For example, you might have a product person coming up with a great product idea that customers will love, whilst the salesperson struggles to figure out how to best commercialise it. Or the engineer who wants to make the software code more elegant, seemingly immune to the pressure to take the product to market as quickly as possible. These tussles can make the difference between being first to market or a product never seeing the light of day; between customer delight and customer indifference; between customer value and commercial realism.

For the purposes of this book, I define product management to include both building the product and its subsequent management and iterations throughout the product life cycle.[3] There will be parts of the book where I will zero in on developing a product or feature, and other places that highlight the continuous iterations of a product. The three core components of product management, each of which, in their own right, can cause tension are mind, matter and moves.

Tensions caused by the ‘Mind’ of the individuals and teams involved with the product, their attitudes, approaches and mental states.

Tensions caused by the ‘Matter’ of which the product is formed. Whether the matter of your product is technological or physical, it might not always ‘act’ the way we want or predict it to.

Tensions caused by the ‘Moves’ made with respect to the product. Moves such as decisions to create or terminate a product or the processes we put in place to manage a product throughout its life cycle. Not only do we need to be aware of the distinctive tensions inherent within mind, matter and moves individually, we also encounter tension as a result of friction between different factors or due to specific circumstances. The mind of people involved in developing products, for instance, can be rather unpredictable. This doesn’t have to be problematic in its own right but will lead to friction or uncertainty if the product matter is very unpredictable or if the moves designed to guide the product development process hinge on certainty. Or take a totally unprecedented circumstance like the COVID-19 pandemic which has caused a lot of tension in its own right. Tension is therefore the cumulative result of cause, effect and circumstances which manifests itself in a multitude of ways when managing products:

- Uncertainty

- Friction

- Creativity

- Tough decisions

- Ambiguity

- Challenges

- Constraints

- Unclear territory

- Problems

- Opinions

- Doubt

- Anxiety

- Conflict

Better understanding of both the reasons and manifestations of tension is critical if we want to improve the ways in which we manage them when creating products. Take ‘people and technology’, for example; this tension alone can completely derail the development of your product. In this book I will argue that tension is neither good nor bad. Tension is inevitable and it is down to us to manage tension effectively.

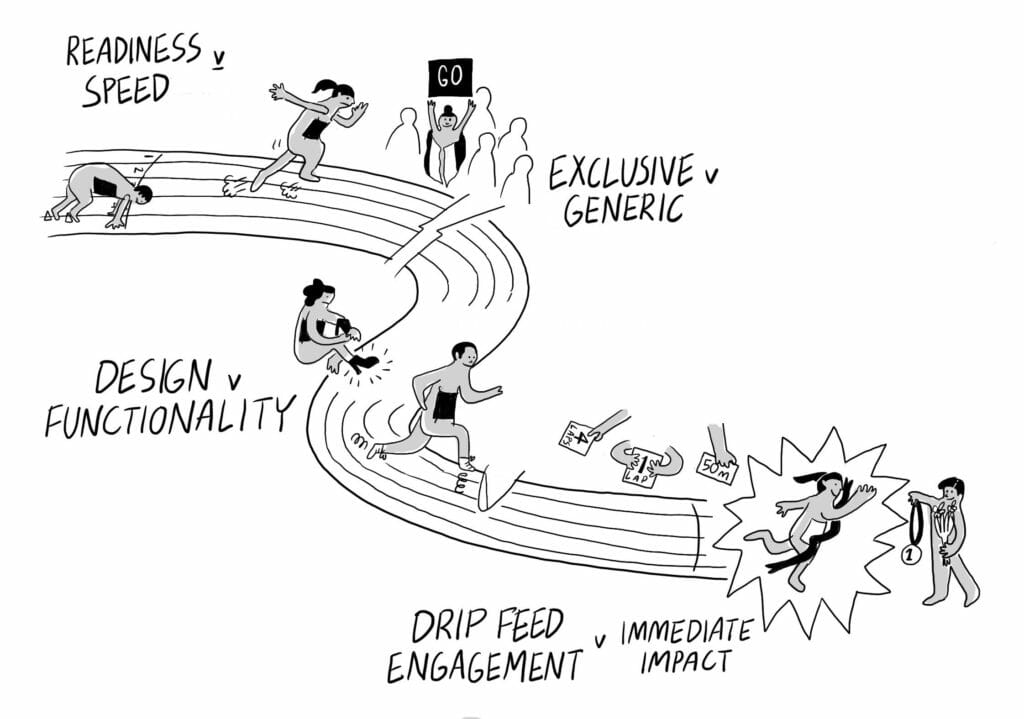

The nature of product management gives rise to multiple tensions and, if we are not careful, it could leave a mark on the product and impact its value to the customer (See fig. 1). In this first chapter we will see the tensions heaped on the product, caused by the mind, matter and moves respectively.

Product Management = Mind + Matter + Moves

‘Since new developments are the products of a creative mind, we must therefore stimulate and encourage that type of mind in every way possible.’ George Washington Carver

When I took on my first role as a product manager, I was very excited. One of the reasons for my initial excitement was that I expected to focus solely on products, no longer having to worry about dealing with other people, their personalities and agendas. Or that’s what I thought. The reality of being a product manager could not be further removed from my initial assumptions: These days, I probably spend eighty percent of each day interacting with other people!

Don’t be fooled into thinking that the problematic nature of product management is all down to products and the technologies or materials that they are made of. The mind of the person(s) involved in designing, building and marketing products are just as pivotal. At the start of this first chapter we talked about the inherent tension between technology and people. Collaborating effectively with other people can be just as complicated, if not more so. In this section, we will look at the following challenges to cognitive diversity and collaboration, as well as the existence of emotional triggers.

Product Management = Mind + Matter + Moves

Three tensions caused by the mind when managing products:

1. The ‘Not Seeing the Wood for The Trees’ tension.

2. The ‘Dysfunctional Family’ tension.

3. The ‘You’re Only Human’ tension.

1. The ‘Not Seeing the Wood for The Trees’ tension

‘What you really want is people to solve problems in diverse ways ‒ to have a creative team, you want people to think of different types of ideas.’ Scott Page

Product management is a team sport. When I interview product management candidates for a role on a product team, I always explore the products they have worked on. When I hear candidates talk about ‘I built_____’ or ‘I acquired ______ new customers’ I probe to find out about both their specific individual contribution and how they collaborated with others.[4]

The main reason why I am always keen to explore collaboration, as well as individual contributions, is because of my strong belief in the value of ‘cognitive diversity’ which occurs when different perspectives and problem-solving approaches come together.[5] Creativity triggers a focus of critical judgement, rather than a suspension of it; as creators master their own creative process, less and less is left to explore alternatives. Instead, creators aim to try and get to their desired final result as quickly and efficiently as possible.[6] Going through such a creative process collectively therefore generates pressure and opposing points of view, starting with reaching agreement about the desired end result, let alone figuring out as a team how best to get there.

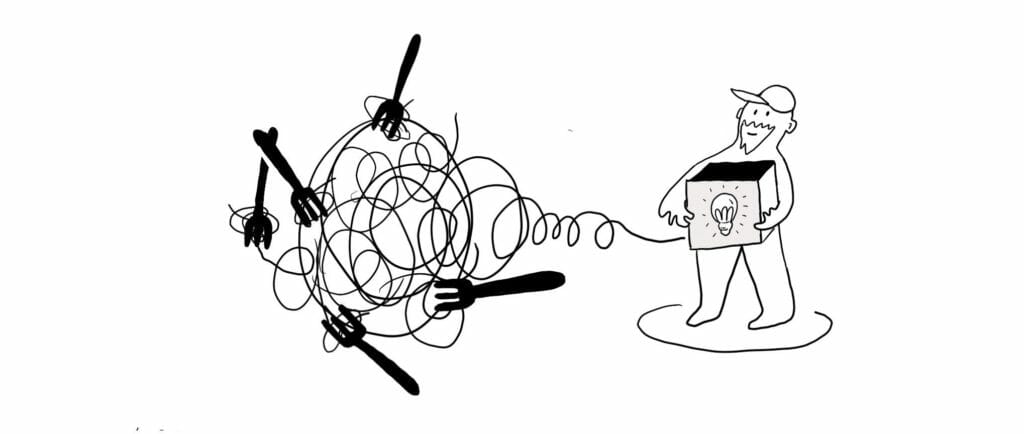

Cognitive diversity is closely linked with so-called ‘healthy tension’ or ‘constructive conflict’ which, if exercised wisely, fuels innovation and team success.[7] In both instances, people will respect each other’s different perspectives and opinions, and aim to resolve issues in a productive manner. Achieving a state of productive disagreement sits in the middle of the ’Conflict Continuum’ developed by business author Patrick Lencioni.[8] In this continuum, productive disagreement is flanked by artificial harmony and destructive conflict. At first glance, the idea of ‘artificial harmony’ might sound appealing but there is often a lot of discontent hiding underneath the group agreement or it risks being based on the lowest common denominator. Equally, a state of deconstructive conflict is not desirable either. Whilst it is impossible ‒ and as I will point out later in the book, not conducive to product innovation ‒ for team members to always agree, we don’t want teams to be in a state of conflict that doesn’t move the team or the product forward (See fig. 2).

In reality, I see an additional dimension playing out; ‘noise’ caused by people sharing their viewpoints haphazardly and not listening to each other. We thus get caught up in a cacophony of split perspectives, losing sight of what really matters or what is actually happening. In my experience, cognitive diversity becomes troublesome when people don’t respect or trust different views or approaches, have divergent interests or follow different goals. You might have come across companies or teams where people only pay lip service to the concept of cognitive diversity. Equally, friction rears its head when people fail to shed deeply-held biases.[9] As much as we like to see ourselves as totally rational beings, the reality is that we aren’t.

Throughout our lives, we develop so many different learnings and biases, some more ingrained than others. Unlearning these ‘priors’ can be really tough and cause friction between people and teams.[10] As a consequence, this often simply creates noise, with people failing to reach agreement on anything. Wayne Greene, a highly experienced product management leader and consultant, has reflected on this noise and compared it to ‘walking into a dysfunctional family’. Greene explained to me how product managers might feel like a ‘mini CEO’, owning the product, but the reality is that ‘you almost need a degree in psychology’ when working with others on products.[11] Cognitive diversity is priceless with respect to developing great products, but we need to recognise that it can also cause a great deal of friction.

2. The ‘Dysfunctional Family’ tension

‘They did not need to be close friends to work together. But they need to trust each other.’ Kirsten Beyer

Spotify is a great example of a collaborative approach to product management. About ten years ago, they introduced their ‘squad’ structure, which represents their cross-functional approach to product development. Each squad is designed to act as a self-contained unit, consisting of a product person, designer and engineers. The squad should thus have all the skills and tools needed to design, develop, test and release to production.[12] Naturally, Spotify’s approach has evolved since its introduction, and Spotify employees are at pains to stress that they never set out to create a ‘Spotify model’ and that squads were only meant as an output and not as a goal in its own right.[13] In other words, it is a common misconception to think that assembling squads will automatically get people to collaborate effectively.

I have been fortunate enough to have worked in a squad-like fashion, working closely with engineers, designers and testers on a day-to-day basis. However, I have also come across businesses where collaboration wasn’t a given. For example, I joined a company a good few years ago which had an impressive engineering team and a team of equally committed project managers. Notwithstanding everyone’s good intentions, the two teams operated as silos, and cooperation between ‘tech’ and ‘project management’ was limited. Instead, it felt more like there was an imaginary fence between the two sides with people tossing things to each other over the top of it.

In her article ‘The Collaboration Blind Spot’, Harvard University researcher Lisa B. Kwan writes about why groups of people can feel threatened when they are being asked to collaborate.[14] From her research, Kwan has found that resistance to collaboration tends to emerge ‘especially when those groups are being told to break down walls, divulge information, sacrifice autonomy, share resources, or even cede responsibilities that define them as a group.’[15] People can thus interpret collaboration as a sign that their own importance to the company ‒ as a team or individual ‒ is waning. As a consequence, they become defensive and uncommunicative in trying to protect their area or role. Having seen such behaviours play out first-hand, collaboration can add an additional layer of complexity to the product development process.

‘Collaboration is rarely all bliss’ claims Allen Gannett in his book ‘The Creative Curve’, and so-called ‘conflicting collaborators’ are the best people to work with, according to him. You don’t want to, Gannett explains, collaborate with someone who is so easy to get along with that they don’t push you. Instead, you want to work with someone who will help you discover and overcome your flaws or those of your creative idea.[16]

A conflicting collaborator has specific traits which compensate for your flaws.[17] Let’s say that Rosy has great product ideas but struggles to turn them into action. Kevin, a colleague of Rosy, isn’t necessarily the best at coming up with ideas; his forte is the practical execution of other people’s ideas. Paired together, Rosy and Kevin form a great team, and complement each other well.[18] Their productive partnership is then thrown off track when Mona joins the team; she brings a wealth of experience but finds it hard at times to venture beyond what she already knows. As this simple, fictitious example shows, collaboration is hardly ever straightforward, and putting complementary skills together will not create a high-performing team overnight. However, if managed well, collaboration can act as a strong source of creativity and innovation.

3. The ‘You’re Only Human’ tension

‘Our emotions have a mind of their own, one which can hold views quite independently of our rational mind.’ Daniel Goleman

As Sylvester Stallone’s character once said in the film ‘Rocky’, ‘In the boxing ring of life it’s not how hard you can hit, but rather how many times you can get hit and keep moving forward.’ This quote is spot on when it comes to emotional triggers; you will feel a blow each time your weak spot is hit; however, the test is whether you have the resilience to continue. Before you ‘feel’, you are likely to experience an emotion first.[19] Emotions are effectively a survival mechanism, an instant response which in turn triggers a certain feeling.[20]

Emotional triggers are people, words, opinions or situations that provoke a strong emotional reaction within us. In her famous TED talk, neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett explains that emotions are rooted in predictions.[21] She explains that emotions are primal, helping us to make sense of the world in a quick and efficient way.[22] It’s our past experience that our brain uses to predict and trigger associated emotions.

Emotions that can be triggered include anger, rage, sadness and fear.[23] For example, when other people disagree vehemently with my view of the world, I will often feel sad and lonely. Over the years I have at least become aware of this trigger and its impact, but it can nevertheless affect the way in which I collaborate with others or the ways in which I behave.

I once worked with a colleague who other colleagues described to me as ‘a tough cookie’. Granted, he was a bold character who wasn’t afraid to stand up for his opinions and take drastic action. I realised, however, that my colleague was still susceptible to what other people thought of him, often asking ‘what do people think of me?’ or ‘what did they think of my decision?’ A clear example of someone who appeared to be made out of Teflon, whilst in reality having his own emotional triggers to deal with.

When your emotions are triggered, Dr. Marcia Reynolds explains in ‘Outsmart Your Brain’, a host of neural, biochemical, and hormonal actions are initiated based on what your brain perceives you need to feel happy or satisfied.[24] Psychology professor Michael Gazzaniga argues that people have a built-in system which creates a narrative about why we do the things we do and which helps decide how we respond to certain triggers. Both Gazzaniga and Reynolds explain how we react emotionally if the following needs or desires are not being met[25]:

- To be liked

- To be understood

- To be in control

- To be included

- To feel valued

- To be right

- To feel needed

- To be respected

- To feel safe

Understanding your emotional triggers is essential in any walk of life. But when you are managing products and the level of collaboration that comes with that, recognising your own and others’ emotional triggers is absolutely imperative. Even if the number of people involved with a product is small, these people will most likely have diverse backgrounds, disciplines and perspectives. Their emotional triggers and personal styles will most likely vary too.

When collaborating with others we need to be aware of these differences and be respectful of dissimilar emotional triggers ‒ our own and those of others. People’s failure to recognise and manage emotional needs or triggers ‒ their own or those of others ‒ can introduce an extra level of frustration to the already uncertain endeavour that is product management.

Product Management = Mind + Matter + Moves

‘The test of the machine is the satisfaction it gives you. There isn’t any other test. If the machine produces tranquility, it’s right. If it disturbs you it’s wrong until either the machine or your mind is changed.’ Robert M. Pirsig

Learning about the definitive nature of software code …

I am not a software engineer myself and perhaps that is one of the reasons why I have always been in awe of engineers and the work they do. When I started my career in the digital space, I remember a colleague explaining to me that ‘coding is pretty black and white’, as she showed me the code that she had just written. It took me a while to make sense of her code, but I could see how she had created a set of instructions and rules for when to apply them.

My colleague then taught me about basic ’if statements’ in a common coding language, meaning that you need a set ‘condition’ to be true for a specific instruction or ‘statement’ to be executed. If the condition is false, then the statements get ignored:[26]

if(condition_1) {

/*if condition_1 is true execute this*/

statement(s);

}

else if(condition_2) {

/* execute this if condition_1 is not met and

* condition_2 is met

*/

statement(s);

}

In short, get an instruction wrong and the product won’t behave in the way you expect it to!

The story above illustrates the certain character of software programming, with the onus on the software engineer to make sure that the instructions put in are (a) the correct ones and (b) executed as expected. Until machine learning takes hold fully, computers will be dependent on humans feeding instructions, and those humans not messing up their commands.

Craig Strong, Global Speciality Practice Advisory Lead for EMEA at Amazon Web Services, emphasises the effort required to develop software solutions, which can be high in cognitive load and complexity. ‘Changes which seem simple to some people can in fact be a lot of technical work.’ For instance, code inheritance, domain logic, rules and technology dependencies. Strong adds: ‘I’ve witnessed many people with little knowledge on the technology side be very dangerous in this context, manifesting disrespect for the tech. As a result, they underestimate the time something should take to develop or disrespect the proposed timelines from the tech team which can in turn can cause human conflict.’[27]

Whether the product is an app, website, API, self-driving car or smart speaker, errors in the code written can cause ‘crashes’ or ‘bugs’. Whilst Basecamp co-founder David Heinemeier Hansson argues that ‘bugs are an inevitable byproduct of writing software’, most engineers will strive ‒ as a matter of professional pride, if anything ‒ to reduce any room for error.[28] Software development can be very complex, both when working on existing systems or implementing new technologies. This is the reason why coding is such a painstaking, almost binary discipline. Its focus is on eliminating any sense of ambiguity, aiming to make the software as repeatable and predictable as possible.[29]

Product Management = Mind + Matter + Moves

Three tensions caused by the matter when managing products:

1. The ‘Tell Me What to Do’ tension.

2. The ‘Knitting Spaghetti’ tension.

3. The ‘Who’s the Boss’ tension.

1. The ‘Tell Me What to Do’ tension

‘For good ideas and true innovation, you need human interaction, conflict, argument, debate.’ Margaret Heffernan

Involving humans in product management can equate to opening the floodgates for the herd. Products are never developed in isolation; from making product decisions to people building and using the product, humans are heavily involved at every stage. Despite this being a good thing for the most part, the combination of technology and people can lead to clashes and frustration.

The creation of products leaves little room for ambiguity, but humans are not built like that. Products are designed and built in a highly rational and calculated manner. For instance, when designing and building a car, the different materials and components that make up the car dictate its design and build. Materials like steel and aluminum aren’t particularly malleable and don’t leave much room for nuance! As humans, in contrast, there will be times when we make fully rational decisions and times when we clearly don’t.[30] At times, emotional or contradictory thoughts or behaviours will take over.[31] In addition, creativity requires a healthy degree of irrationality. Would we have had the lightbulb or the automobile if people had complied with the status quo or accepted, logical ways of thinking?!

Bringing a group of people together as part of product development means introducing emotion, creativity, uncertainty, contradiction and a whole host of other behaviours. If you offset this against the more rational, predictable nature of technology products, you have got the second cause for product management tension

2.The ‘Knitting Spaghetti’ tension

‘Creativity can solve almost any problem.’ George Lois

The world’s greatest products and inventions wouldn’t be anywhere without creativity, and creative geniuses spurring them on. From Thomas Edison to Steve Jobs, the most famous product people and inventors all share one key trait: creativity. Some of these visionaries are well known for displaying ‘challenging behaviours’: Steve Jobs and his tendency to erupt in anger or Marie Curie’s insistence on working with highly radioactive materials.[32]

Creativity is an intangible phenomenon and can’t be captured in checklists or fixed processes; creativity means coming up with original or unusual ideas, which can be applied to existing or fresh problems. Especially when working on problems that haven’t yet been solved (successfully) you will need to think in novel and unexpected ways. Solving these problems involves uncertainty, unknowns and relentless iteration. Take British inventor James Dyson, who set out to solve the problem of traditional vacuum cleaner bags rapidly filling up with dust and losing suction power as a result. Dyson went through thousands of prototypes to finally come up with a vacuum cleaner that used centrifugal force instead of a bag, to successfully separate dirt from air.[33]

Such an evolution becomes even more of a challenge when coupling innovation with heavily regulated industries or process driven companies. Would Steve Jobs have become such a prodigy had he manufactured airplanes? How would Sara Blakely, founder of Spanx, have fared if she had worked in the pharma industry as opposed to underwear?[34]

The impalpable nature of creativity can be a breeding ground for frustration when developing products. Creativity is hard to direct and cannot be delivered on demand. In Chapter 3 we will examine the nonlinear nature of creativity, and the unpredictable outcomes of divergent perspectives coming together. This clashes with the demanding nature of all competitive and pressurised environments.

3. The ‘Who’s the Boss’ tension

‘Managers who do not understand people’s different thinking styles cannot understand how the people working for them will handle different situations.’ Ray Dalio

One of the things I love about being a product manager is the front row seat that you often get within a business. You will be involved in commercial and strategic aspects as well as technology and design. Product people repeatedly engage with a wide cross-section of people and disciplines, both inside and outside their businesses.

In the space of a typical working day you can have talks with the sales team, discuss a go-to market strategy with a marketeer or sit down with engineers to plan implementation. These are all ‘stakeholders’ that a product manager needs to engage with. Marty Cagan, an internationally renowned product management expert and author, lists the following stakeholder examples:[35]

- The executive team ‒ The CEO and leaders of finance, marketing, sales and technology.

- Sales and Marketing ‒ To make sure the product and the business are aligned.

- Finance ‒ To make sure the product fits within the financial parameters and model of the company.

- Legal ‒ To make sure that what you propose is defensible.

- Compliance ‒ To make sure what you propose complies with any relevant standards or policies.

- Operations ‒ To make sure that people at the front line of your business, e.g. working on the supply chain or in customer support, know about your product or can work with it.

- Business Development ‒ To make sure what you propose does not violate any existing contracts or relationships.

These people typically also bring their own approaches to problem solving and I strongly believe that cognitive diversity can contribute significantly to great products and high-performing teams. The downside of having such a rich diversity of views and approaches, however, is the risk of much ’noise’ or ‘analysis paralysis’:

- ‘Who makes the decisions around here?!’ ‒ Think of the marketeer, the salesperson or the business owner all having a view on the product or how to solve a customer problem. It is plain to see how endless debates can ensue without ever reaching a decision.

- ‘Can we please agree on an approach to solving the problem?’ ‒ Similarly, if a problem has been agreed but there are a multitude of potential approaches to solving a problem, how do you identify the best approach quickly and efficiently?

- ‘We’re not all in the same place!’ ‒ Especially when stakeholders are not collocated in the same place, communicating and collaborating effectively can be a thorny affair.

Product Management = Mind + Matter + Moves

‘If the path be beautiful, let us not ask where it leads.’ Anatole France

Product Management = Mind + Matter + Moves

Three tensions caused by the moves when managing products:

1. The ‘Hold on To Your Seat’ tension.

2. The ‘I Love It When A Plan Comes Together’ tension.

3. The ‘You Can’t Have It All’ tension.

1. The ‘Hold on To Your Seat’ tension

‘The only way to win is to learn faster than anyone else.’ Eric Ries

Success is never guaranteed when you are developing a new product or iterating on an existing product. Unless you are a market leader or a monopolist, there are so many factors that determine product success. Will customers want the product, and pay for it? How about that pesky competitor that managed to get to market first? What about that new technology that we still know so little about? These are the kinds of factors that companies struggle to control and why product management is not a straightforward or linear process.

Waze: the uneven path from a tiny startup to a $1 billion exit

If there only was a magic recipe or checklist with all the steps required to create a successful product … A few years ago, I attended a lecture by an Israeli entrepreneur who told the story of the humble beginnings of a GPS navigation app, and all the mistakes he and his colleagues made in building their product. Uri Levine was the name of the entrepreneur and ’Waze’ the name of the app, which was eventually sold to Google for a hefty $1 billion. From shifting focus to dealing with gnarly technology and scaling issues, Levine painted a vivid picture of the bumpy road travelled when building Waze.[36] His story made me realise that there is no special blueprint for managing successful products. By contrast, managing products often feels more like playing a pinball machine, having to carefully navigate the multiple flippers within the machine.

Ever driven a car in the mountains? Going from curve to curve, without knowing what is around the next bend? That is what managing products often feels like. Successful product companies like Amazon have developed a knack for taking the mountainous curves as expeditiously as possible so that they can learn quickly what awaits around the other side of the mountain.[37] Amazon founder Jeff Bezos has said ’Our success at Amazon is a function of how many experiments we do per year, per month, per week, per day.’[38]

Learning early and often helps to minimise risk but can in turn create a huge amount of uncertainty and ambiguity. Product people will embrace this ambiguity; often out of choice or simply dictated by the circumstances they operate in. This appetite for uncertainty often conflicts with how the rest of the organisation functions. Hope Gurion, an experienced product leader and coach, pointed out to me that ‘the way product works is so countercultural to how the rest of the organisation operates. Think about accounting and sales, for example, where things tend to be a lot more predictable and certain, whereas products are flying in the face of uncertainty.’ Gurion went on to explain how product people often question or assume things will go wrong, ‘with everybody else assuming that things will go right.’[39] Consider the scenario where we start an experiment or ‘spike’ a new technology, not having any certainty about outcomes of these experiments.[40] In a world where people are looking for certainty and predictability, the experimental nature of product management can introduce significant pressure.

2. The ‘I Love It When A Plan Comes Together’ tension

‘In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.’ Dwight D. Eisenhower

My thinking that projects would materialise exactly as planned …

As I mentioned earlier, before I became a product manager, I used to work as a digital project manager. At the beginning I managed a lot of government projects, and I had to create project plans in Microsoft Project. Each time I put together such a plan for, let’s say, the build of a website or an app, the world felt like a better and more certain place. In my project plans, things always happened according to plan within the set timeframes, seamless handovers between different teams, everything according to spec and all within a pre-agreed budget. Any project dependencies would be dealt with smoothly by the various people involved in executing the project …… sounds of breaking glass.

I have learned over the years, and the hard way, that working on technology projects or products does not follow a linear or predictable path. Plans are malleable or, as the quote by Fujio Cho, Chairman of Toyota Motor Company, goes: ‘Plans are things that change’. These are just some of the things that I have seen go wrong when working on software products:

- Unexpected complexity ‒ The underlying technology or workflows turn out to be way more complex than expected. As a result, thinking about, writing and testing software code takes longer than anticipated.

- Altered scope ‒ We all say that we should not be doing it, but it still happens regardless: scope creep. Specific product features are agreed, often complemented with a list of things that are not in scope, upfront. As soon as we start working on a product, a request comes from left field, suggesting: ‘wouldn’t it be nice to have _____.’

- Communication breakdown ‒ People responsible for different aspects of the product fail to communicate effectively with each other. The development process thus becomes a relay race where colleagues drop the baton in an effort to pass it on. Think, for instance, of the designer who has spent a lot of time designing an elaborate user interface, which the engineer then says cannot be implemented …

- Change in priorities ‒ Whilst the product team has committed to building a specific product or feature, a new commercial opportunity arises for the sales team and a revision of priorities is required. Or your biggest competitor has just launched a similar feature. This often means that teams have gone back to their product roadmaps to discuss whether it makes sense to deviate from the items on the roadmap.[41] This can generate significant friction if the organisation treats the roadmap as a set in stone plan, an artefact that promises certainty and predictability …

Managing products is an uncertain business. It is therefore an illusion to think (1) that we can fully control a successful execution of a plan and (2) that everything will go as planned. However, this does not make planning or roadmaps redundant; a product roadmap is a beneficial communication and collaboration tool, as long as we accept that we might have to deviate from what was initially planned.

3. The ‘You Can’t Have It All’ tension

‘A compromise is the art of dividing a cake in such a way that everyone believes he has the biggest piece.’ Ludwig Erhard

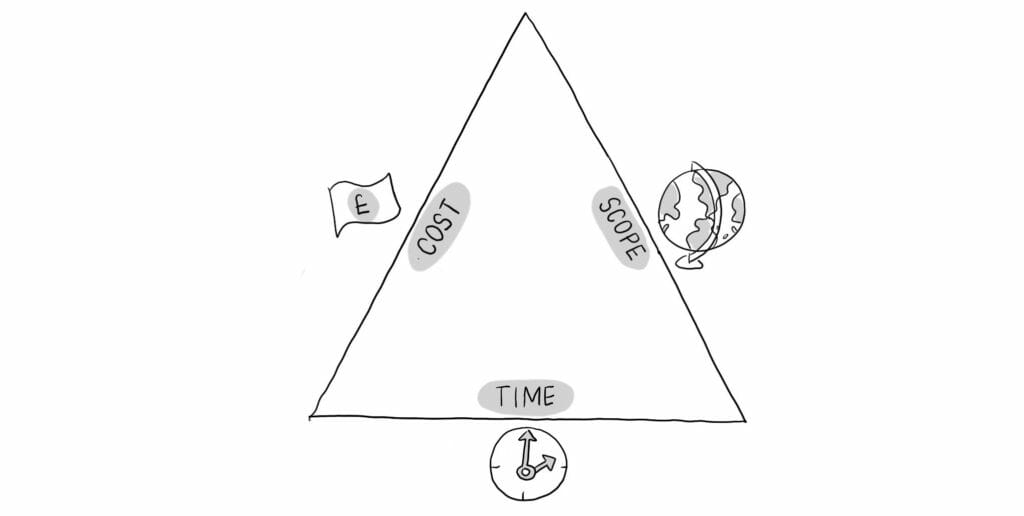

A significant part of managing products comes down to successfully handling constraints and making tough trade-off decisions. As Brandon Chu, VP of Product & GM of Platform at Shopify, explains, ‘product teams are constrained by the money, people, and time they have to launch a product.’[42] In project management this is referred to as the ‘Iron Triangle’, with its three angles occupied by cost, scope and time (See fig. 3).

However, when it comes to product management, teams can often have all three variables in play at one time, which continuously changes the shape of the triangle. Alex Watson, Head of Product at BBC News, says ‘it is well known that if you fix two sides of a triangle, the third is what has to flex.’[43] Teams can thus be held back by all three of these constraints when working on a product, which means that you will have to compromise on cost, time and quality ‒ sometimes one of these or all three at once ‒ related to your product or business:[44]

People ‒ This is often the biggest constraint, as most companies have a limited number of people that can work on a problem at a given time. It can, however, be made even worse in companies when teams lose focus as a result of switching their attention between various products.[45] John Medina, a Developmental Biologist, has studied the brain and our ability to multitask. Contrary to popular belief, he has found that our brains are not conditioned for multitasking, actually slowing us down and increasing errors by 50 percent.[46] Similarly, our instinct to simply throw more people at a problem has also proven to be inadequate, often causing delays to software projects, as it takes time for people to get up to speed and to manage communication overhead due to the increased number of people working on the same project.[47]

Cost ‒ How much does it cost to develop a new product or to iterate on an existing one? Typical cost components are (1) salaries to hire and pay the team (2) marketing and business development to drive the product’s go-to-market strategy (3) operations to maintain a product and (4) operational and capital expenditure to enable teams to iterate on the product.

Timings ‒ Given that time is a finite resource, you will have to make difficult decisions that will affect ‘speed to market’, i.e. how quickly a product or feature can be launched.[48] A team might be working on Product A, but is then asked to work on Product B. If the decision is made for the team to move its focus from Product A to B, the release timings of Product A will suffer as a result. This concept is called ‘cost of delay’ which can be calculated by taking the projected value of a product or feature, dividing it by the duration of its build. Businesses suck up the value of each product or feature until it and any items preceding it are delivered.[49]

Long-term vs short-term ‒ Compromises can enable parties to achieve a desperately needed short-term ‘win’ that boosts morale, moves the business forward or simply generates badly needed revenue. These tend to be more short-term goals which can well be at odds with long-term business objectives.[50] Jo Wickremasinghe, Product Director at Zoopla and someone who has worked with and led numerous product development teams, describes the associated challenge for product managers and product development teams of ‘being able to deliver against both short-term and longer-term aims at the same time.’[51]

Competing customer demands ‒ In an ideal world, we would develop products for all the people and build those features that make all our customers happy. Whether you work in a business-to-consumer (‘B2C’) or business-to-business (‘B2B’) environment, you will have to choose between often conflicting customer demands, simply because product resources are limited.[52]

New vs existing products ‒ Think of it like going to the casino; as a company, which products do you place your chips on? Do you go all in on new products, or instead spread your bets between existing and new products? Not only is this important from a strategic perspective, it also determines how you allocate time, budget and people. The aforementioned Craig Strong shares how he has witnessed times where resentment surfaces between existing product teams and business units: ‘the signal that these new products are the future, sends a signal to the other areas that they are the past.’ Strong has seen the subsequent tension between product teams play out in pretty undesirable ways: ‘I recall a time where I was in a very large tech company and I was working on the new innovative product. I heard many times from the main function in the business “that’s never going to work” and off the back of that resources were limited and delayed. It thus created competition for resources or delays internally where integration was required.’[53]

Product is a results business ‒ At the end of the day, building and managing products is all about achieving results. For the customer and for the business. Even when we talk about creativity or building the unprecedented, both are geared towards realising specific results. Take the famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright, who when designing a house, would first conceive of the result that he wanted to create. As Wright stayed focused on the results he wanted to create, the ‘how’ of obtaining those results emerged organically, and only after the ‘what’ had been crystalised fully.[54] However, even determining product success can be a tense process. Hope Gurion explains that the friction here does not have to be a bad thing: ‘This target setting creates healthy tension, because it requires critical thinking by all people involved. It fosters tension ‒ healthy ‒ around success criteria.’[55]

The very nature of product management is a true breeding ground for tension. Whether it is the often-uncomfortable marriage between humans and technology or the necessity to compromise, frustrations and frictions are innate to developing products.

Conclusion

Managing products is a strenuous business. There are three overarching factors responsible for this strain: the very nature of product management, the substance which makes up the product and the fact that people are involved in each aspect of building products. We need to acknowledge the existence and impact of these three factors before we can start thinking about how to best manage product tensions.

SUMMARY

How the very nature of product management lends itself to tension:

- Designing and building products is like an everlasting tug of war, with various forces pulling the rope in lots of different directions at the same time.

- There are three main forces that are constantly trying to pull the product into different, and often opposing, directions: the mind of the people involved with the product, the matter that the product is made of and the moves that people make in relation to the product.

The impact of the mind on the product:

- Disagreement and friction between the people involved with the product.

- The multiple, and often opposing, minds when collaborating.

- The emotional triggers that are sparked when managing products.

The impact of the matter on the product:

- Leaves little room for ambiguity or nuance when creating products.

- The substance of the product ‒ e.g. software code or raw materials ‒ puts constraints on human creativity.

- Multiple people working on the product matter cause friction and ‘noise’.

The impact of moves on the product:

- Products are surrounded by so much uncertainty that it is hard to predict things ‒ as product managers we are walking an uneven path.

- Your moves in relation to the product will rarely go fully according to plan.

- The constant need for tough trade-off decisions causes a lot of tension.

Now you’ve Started…

If you’ve enjoyed this chapter, you can also read chapter 5, ‘Leaning into Tension Effectively’. Chapter 5 is packed with information, ideas and practical exercises – read Chapter 5 now. Alternatively, you head on over to Amazon to buy the book and read the whole thing!

References

[1] See for an explanation of the difference between project and product management: “What’s the Difference Between Program, Product and Project Managers?,” David Goulden, June 17, 2017, https://www.clarizen.com/whats-difference-program-product-project-managers/;

“Product Manager vs Project Manager,” Andrei Tit, Medium, March 20, 2018, https://medium.com/paymo/product-manager-vs-project-manager-b4ac603d872a; “Project Manager vs. Product Manager,” Brainrants | Brainmates Blog, Updated October 2019, https://brainmates.com.au/brainrants/project-manager-vs-product-manager/.

[2] A Gantt chart is a type of bar chart that illustrates a project schedule, named after its inventor, Henry Gantt, who designed such a chart around the years 1910–1915.

[3] “Exploit the Product Life Cycle,” Theodore Levitt, Harvard Business Review, November 1965, https://hbr.org/1965/11/exploit-the-product-life-cycle.

[4] “My product management toolkit (31): hiring product managers,” Marc Abraham, October 5, 2018, https://medium.com/@maa1/my-product-management-toolkit-31-hiring-product-managers-4442740af77.

[5] See: “The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools and Societies,” Scott Page, Princeton University Press, 2008; “Teams Solve Problems Faster When They’re More Cognitive Diverse, “ Alison Reynolds and David Lewis, Harvard Business Review, March 30, 2017, https://hbr.org/2017/03/teams-solve-problems-faster-when-theyre-more-cognitively-diverse; “Cognitive Diversity: what’s often missing from conversations about diversity and inclusion,” Sara Canaday, Psychology Today, June 18, 2017, Psychology Today, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/you-according-them/201706/cognitive-diversity ; “How Diverse Leadership Teams Boost Innovation,” Rocío Lorenzo, Nicole Voigt, Miki Tsusaka, Matt Krentz, and Katie Abouzahr, Boston Consulting Group, January 23, 2018, https://www.bcg.com/en-us/publications/2018/how-diverse-leadership-teams-boost-innovation.aspx.

[6] Robert Fritz, The Path of Least Resistance (New York: Fawcett Columbine, 2nd Edition, 1989, p. 39).

[7] See: “Four Questions to Spot the Difference Between Healthy Tension and Unhealthy Conflict ,” Eric Geiger, January 18, 2016, https://ericgeiger.com/2016/01/four-questions-to-spot-the-difference-between-healthy-tension-and-unhealthy-conflict/; “Healthy tension in product teams,” Emmet Connolly, Inside Intercom, July 21, 2017, https://www.intercom.com/blog/healthy-tension-in-product-teams/; “What is healthy tension?” Tim Arnold, Leaders for Leaders, https://www.leadersforleaders.ca/blog/entry/what-is-healthy-tension; “Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument,” Kenneth W. Thomas and Ralph H. Kilmann, Profile and Interpretive Report (sample), CPP Inc., May 1, 2008.

[8] Patrick Lencioni, The Five Dysfunctions of a Team (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, April 2002).

[9] “Why Diversity Programs Fail,” Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev, Harvard Business Review, July-August 2016, https://hbr.org/2016/07/why-diversity-programs-fail.

[10] “The Dominant Logic: Retrospective and Extension,” Richard A. Bettis and C.K. Prahalad, ,Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 16, Issue 1, 1995, http://213.55.83.214:8181/Economics/Economy/00539.pdf.

[11] Wayne Greene, interview by author, San Jose, June 27, 2019.

[12] “How Spotify builds products,” Henrik Kniberg, Crisp’s Blog, January 13, 2013, https://blog.crisp.se/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/HowSpotifyBuildsProducts.pdf.

[13] See: “The Spotify Model Is No Agile Nirvana ,” Ben Linders, InfoQ, October 12, 2017, https://www.infoq.com/news/2017/10/spotify-agile-nirvana/; “Why ‘the Spotify model’ won’t solve all your problems with Product Delivery,” Curtis Stanier, Medium, November 3, 2019, https://medium.com/@crstanier/why-the-spotify-model-won-t-solve-all-your-problems-4c31640c719a; “Failed #SquadGoals,” Jeremiah Lee, April 19, 2020, https://www.jeremiahlee.com/posts/failed-squad-goals/.

[14] “The Collaboration Blind Spot,” Lisa B. Kwan, Harvard Business Review, March – April 2019, https://hbr.org/2019/03/the-collaboration-blind-spot.

[15] Ibid 14.

[16] Allen Gannett, The Creative Curve, (London: Ebury Publishing, June 2018, p. 171).

[17] Ibid 16, p. 182.

[18] See also “The AEM-Cube: A Management Tool, Based on Ecological Concepts, in Order to Profit from Diversity,” Peter Robertson. Presented at the 43rd Annual Conference of the International Society for the Systems Sciences, 1999, Pacific Grove, CA.

[19] Antonio Damasio, Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow and the Feeling Brain (London: William Heinemann, 2003, pp. 29 – 30).

[20] Marcia Reynolds, Outsmart Your Brains: How to Master Your Mind When Emotions Take the Wheel (Arizona: Covisioning, 2nd Edition, August 2017).

[21] “You aren’t at the mercy of your emotions – your brain creates them,” Lisa Feldman Barrett, TED @ IBM, January 2, 2018, https://www.ted.com/talks/lisa_feldman_barrett_you_aren_t_at_the_mercy_of_your_emotions_your_brain_creates_them/.

[22] Ibid 21.

[23] See: The Ekmans’ Atlas of Emotions, http://atlasofemotions.org/.

[24] Ibid 20.

[25] Ibid 21 and “Who Is in Charge?” Michael S. Gazzaniga, BioScience, Volume 61, Issue 12, December 2011, pp. 937–938.

[26] “If else Statement in C++,” Chaitanya Singh, BeginnersBook, August 2017, https://beginnersbook.com/2017/08/cpp-if-else-statement/.

[27] Craig Strong, email to author, March 28, 2020.

[28] “Software has bugs. This is normal,” David Heinemeier Hansson, Signal v. Noise, March 7, 2016, https://m.signalvnoise.com/software-has-bugs-this-is-normal/.

[29] “Software is actually extremely repeatable and predictable for the majority of business applications,” Justin James, Medium, August 11, 2018, https://medium.com/@jmjames/software-is-actually-extremely-repeatable-and-predictable-for-the-overwhelming-majority-of-business-4459aa7fc0b2.

[30] Jurgen Habermas, The Theory of Communicative Action Volume 1, Reason and the Rationalization of Society (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1984); “Study suggests emotion plays a role in rational decision making,” Kate Wong, Scientific American, November 27, 2001, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/study-suggests-emotion-pl/.

[31] Julius Friedrich August Bahnsen, The Contradiction in the Knowledge and Being of the World, 1880.

[32] Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs: The Exclusive Biography (Simon & Schuster, October 2011);

Barbara Goldsmith, Obsessive Genius: The inner world of Marie Curie (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2004).

[33] See: “How to Make It: James Dyson built a better vacuum. Can he pull off a second industrial revolution?” John Seabrook, The New Yorker, September 13, 2010, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/09/20/how-to-make-it; “How James Dyson Makes the Ordinary Extraordinary,” Shoshana Berger, Wired, November 19, 2012, https://www.wired.com/2012/11/mf-james-dyson/; “How we made the Dyson vacuum cleaner,” Andrew Dickson, The Guardian, May 24, 2016, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/09/20/how-to-make-it.

[34] “Interview with Sara Blakely,” Guy Raz, NPR “How I Built This” podcast, July 3, 2017, https://www.npr.org/2017/08/15/534771839/spanx-sara-blakely.

[35] “Stakeholder Management,” Marty Cagan, Silicon Valley Product Group, April 30, 2013, https://svpg.com/stakeholder-management/.

[36] “Lessons learned from Uri Levine, Co-Founder of Waze,” Marc Abraham, As I learn, May 14, 2017, https://marcabraham.com/2017/05/14/lessons-learned-from-uri-levine-co-founder-of-waze/.

[37] “Product management at Amazon – What is it like?” Marc Abraham, As I learn, November 26, 2015, https://marcabraham.com/2014/11/26/product-management-at-amazon-what-is-it-like/.

[38] “Why These Tech Companies Keep Running Thousands of Failed Experiments,” Ben Clarke, Fast Company, September 21, 2016, https://www.fastcompany.com/3063846/why-these-tech-companies-keep-running-thousands-of-failed.

[39] Hope Gurion, interview by author, Greenbrae, December 9, 2019.

[40] “What’s a spike, who should enter it and how to word it?” Andrew Fuqua, Leading Agile, September 13, 2016, https://www.leadingagile.com/2016/09/whats-a-spike-who-should-enter-it-how-to-word-it/.

[41] See: “No more features on product roadmaps – Have themes or goals instead!” Marc Abraham, As I learn, October 1, 2015, https://marcabraham.com/2015/10/01/no-more-features-on-product-roadmaps-have-themes-or-goals-instead/; C. Todd Lombardo, Bruce McCarthy, Evan Ryan and Michael Connors, Product Roadmaps Relaunched (Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly, 2018).

[42] “The First Principles of Product Management,” Brandon Chu, The Black Box of Product Management, January 7, 2018, https://blackboxofpm.com/the-first-principles-of-product-management-ea0e2f2a018c.

[43] Alex Watson, email to author, December 21, 2019.

[44] “Project Management: cost, time and quality, two best guesses and a phenomenon, it’s time to accept other success criteria,” Roger Atkinson, International Journal of Project Management, 1999, Vol. 17, No. 16, pp. 337-442.

[45] “Making Trade-offs is Product Management,” Wayne Greene, This Is Product Management podcast, Alpha, August 2018, https://www.thisisproductmanagement.com/episodes/making-tradeoffs/.

[46] “Brain Rules: The brain cannot multitask,” John Medina, March 16, 2008, http://brainrules.blogspot.com/2008/03/brain-cannot-multitask_16.html.

[47] Frederick P. Brooks, Jr., The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering (Boston: Addison-Wesley Professional, 2nd Edition, August 12, 1995).

[48] “4 Reasons Speed Is Everything in Business,” Adam Fridman, Inc., July 5, 2015, https://www.inc.com/adam-fridman/4-reasons-speed-is-everything-in-business.html.

[49] “My product management toolkit (21): Assessing opportunities,” Marc Abraham, Medium, May 9, 2017, https://medium.com/@maa1/my-product-management-toolkit-21-assessing-opportunities-17f7f6343080; “Breaking down cost of delay: everything you need to know in a simple guide,” Planview Leankit , https://leankit.com/learn/lean/cost-of-delay/.

[50] “Leading Change: 3 Reasons Why Great Leaders Are Reluctant to Compromise,” Aad Boot, LeadershipWatch, August 28, 2013, https://leadershipwatch-aadboot.com/2013/08/28/leading-change-3-key-reasons-why-great-leaders-are-reluctant-to-compromise-2/.

[51] Jo Wickremasinghe, email to author, January 2, 2020.

[52] “Welcome to product management – a city of trade-offs ,” Matthew Tse, UX Collective, April 16, 2018, https://uxdesign.cc/welcome-to-product-management-a-city-of-trade-offs-843c85a5212.

[53] Ibid 27.

[54] Robert Fritz, The Path of Least Resistance: Learning to Become the Creative Force in Your Own Life (Fawcett Columbine, revised edition, 1989, p. 69).

[55] Ibid 39.

Comments

Join the community

Sign up for free to share your thoughts