Defining a product strategy and aligning its execution is one of the most challenging tasks for product leaders. In my book, Product Direction, I take a practical approach to solve this challenge based on artifacts and best practices, to define, link, and communicate your product strategy, to strategic roadmaps, and OKRs.

I'm sharing two chapters of the first section of the book (Setting the Product Strategy) with Mind the Product members:

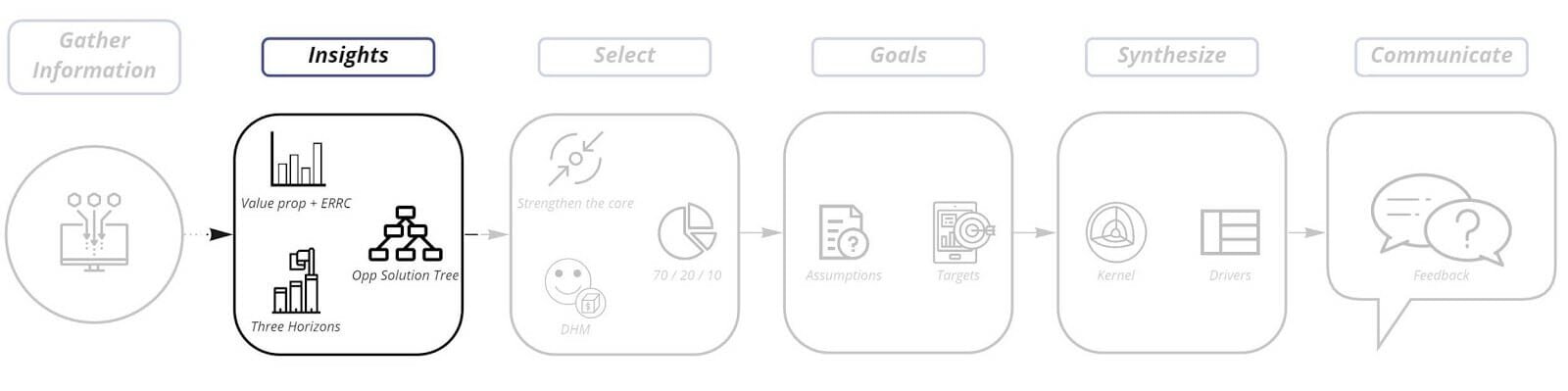

- Chapter 1.4: Insights How to identify insights to define a strategy based on your most promising opportunities

- Chapter 1.5: Select How to select those opportunities that will create a winning and advantageous value proposition

While the book showcases tools and examples, the underlying goal is not to be dogmatic about the process, but rather explain why these decisions are required and provide a few options that you can adapt to your context.

If you like the chapters, you can also buy the book!

Chapter 1.4 – Step 1: Insights

Central to a good strategy is having the right insights. This means identifying a particular problem, trend, or opportunity that can radically change the game. Our goal in this stage is to generate many of these insights to choose the most promising opportunities later.

If you are not feeling particularly creative or inspired, don’t panic. We will explore several tools to help even the most uninspired person (like me) identify options.

In essence, an insight is a learning with a high potential to impact our users’ needs and business results. It’s the kind of learning that we will continuously be searching for during discovery1. In fact, we will have already detected many of these insights by the time we reach the strategy definition phase, where we will work on combining and clarifying them.

Identifying insights is a skill that Product Managers, Product Designers, and Tech Leads should strengthen and develop through practice.

Frameworks to Consider Insights

Before jumping to tools, let’s consider the categories across which insights may be relevant to spark our creativity.

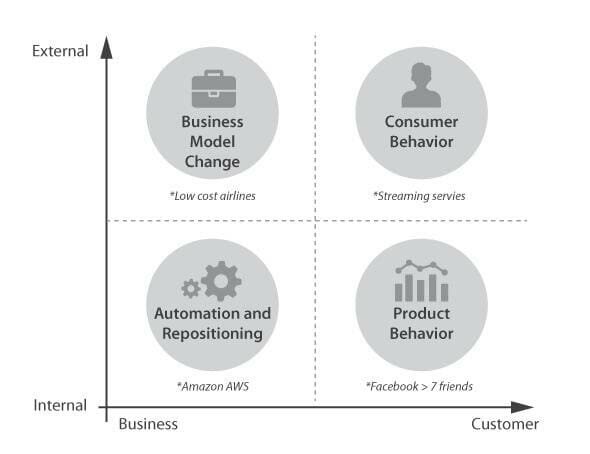

Insights Matrix

Try dividing your analysis into two axes, as seen in Figure 1.4.1.

- The “Internal versus External” axis divides the insights based on the source of information used.

- External information includes research on third-party sources, such as competitors or new technology breakthroughs.

- Internal information focuses on what you can glean from data generated within your own company, such as examples of unexpected product applications.

- The “business-centered versus customer-centered” axis differentiates between changes occurring in our business model versus changes in customer behavior.

The two axes together generate four quadrants. Popular opinion would argue that significant innovations should come from external trends and changes in customer behavior, but this is far from the truth. Let’s explore each of the quadrants.

Internal-Business insight

In this quadrant, we group options related to the automation or repositioning of existing capabilities. We will relate any insight to information about how the company uses a particular resource and its impact. For example, we may have seen a critical business process requiring several people to execute manual operations and taking many days for users to see results. In that case, automation represents a huge opportunity for cost savings, improved speed and consistency, and better customer experience.

Another interesting example in this category might be the opportunity to reposition an internal capability to create a new business. Consider what you might do when your internal information tells you that you are doing something far better than the market. Amazon Web Services is an example of this type of insight. The company had developed an internal capability to provide infrastructure resources for internal teams quickly, and it had unused infrastructure resources. By repositioning these tools to extend the service to external customers, they created one of the most significant revenue sources for the company.

Internal-Customer insight

In this case, we identify opportunities related to the customer’s behavior and use of our product, which might significantly impact the overall product metrics. There is an excellent example of just such an insight in the early days of Facebook. The team detected that users who connected with seven friends within the first few days of joining had a churn rate that was significantly lower than those who hadn’t. Armed with this insight, they modified the initial days’ experience on the platform to help users add those first friends, skyrocketing their retention and growth. Twitter had a similar experience with the number of accounts users followed, which triggered higher engagement levels.

Keep in mind that for strategic purposes, you may not be able to be as precise as these examples suggest. You may know, for instance, that you have a churn rate well below industry average or one that is simply not viable for the business, and you want to focus the strategy on solving that problem (we will get to more detailed insights when we advance to the discovery stages).

External-Business insight

External tendencies are not only related to changes in consumer behavior. Sometimes there may be a change in a whole industry’s ecosystem, a radical change in a part of the supply chain, or something that triggers the opportunity to create a new business model.

Consider the example of low-cost airlines. Customers want to travel from point A to point B, and the things they value the most are usually price and punctuality. By reducing other non-essential features of the service, the low-cost pioneers reinvented the airline business model, offering customers a lower fare while preserving the most valued aspects of the experience.

External-Customer insight

The most clichéd examples of innovation usually involve companies that caught a changing trend in customer behavior. In the digital world, those changes are also often related to a technological change that enabled them. For example, the improvement in internet bandwidth enabled the trends in streaming services.

Sources of innovation

A second perspective for insights is “sources of innovation.” In the book Innovation and Entrepreneurship2, Peter Drucker defined seven different categories.

Inside sources:

- The Unexpected: What has been a surprise success or failure? Is the result a new opportunity emerging?

- Incongruities: What are the pains customers still have with the current solution?

- Process Needs: What company processes can be improved?

- Shifts in Industry and Market Structure: Disruptions or trends in the ecosystem.

Outside sources:

- Demographic Changes: Are our customers changing, or is there a variation in the segment’s size?

- Changes in Perception: Are people perceiving our field differently? How can we leverage that change?

- New Knowledge: Breakthroughs in technological, science, or other fields that can be implemented in our business.

Used as questions, these provide a guide and a systematic approach that helps you identify learning, opportunities, and trends.

Another book, 10 Types of Innovation3 by Professor Larry Keeley, describes how opportunities can be grouped into 3 areas:

- The “Configuration” of the business model and operation.

- The “Offering,” the value the product provides.

- The “Experience” the customer receives from the company.

Similarly, these categories can help you think about different options to improve the value provided by your product.

Insight Tools

By now, we have a good idea of what is expected from an insight and the diverse range of options it can cover. It is now time to list them! Remember that our goal at this step is to generate ideas with impact, hopefully ending up with a wall of “insight post-its” to be used in the subsequent phases.

Given that insights come from deep understanding and reflection about a problem, tools are not required but can prove useful. This is difficult work. What you are trying to do is spark creativity and introduce options you wouldn’t usually consider. To do this, you must deep dive into the information and come up with significant lessons that can be applied.

Previous insights!

Most product teams are attuned to continuous learning. They are continually looking into the product metrics, frequently talking with users, running experiments, and watching company and competitors’ results.

It would be naïve to think we will sit down with a blank sheet of paper to create the strategy, and insights will magically appear. So, the first “tool” to use when reaching this phase is to focus on those past lessons and consolidate them as insights.

Imagine these two examples:

- “The previous strategic exercise focused on sales growth, concentrating on problems we needed to address in the purchase flow. We also identified that we had a potential issue with the post-sales fulfillment experience. Now that we have achieved growth, the post-sales opportunity has become much more relevant.”

In each strategy exercise, you need to select and focus on a few opportunities. Once you’ve had a chance to see and analyze the results of your selected path, any remaining topics can lose or gain relevance, as in the above example. Those that are still important should be reconsidered in the new exercise.

- “We were interviewing customers to understand how to improve the onboarding experience for our content platform, but we realized that many of them are trying to send content to friends and are frustrated because the product does not support that need in anything approaching a friendly way.”

In this case, the team performs discovery work focused on the onboarding problem (that is part of their current Strategy and OKRs), but they found a new opportunity that has high potential. Aligned teams will not pursue the finding immediately, since they are focused on another high-impact goal, but they won’t want to discard it either. They have generated a new insight to review in the next round of strategy or objective setting.

With luck and a little practice, you will be able to generate a long list of these past findings to kick off your insights compilation.

Insights Tool 1: Core value proposition + ERRC

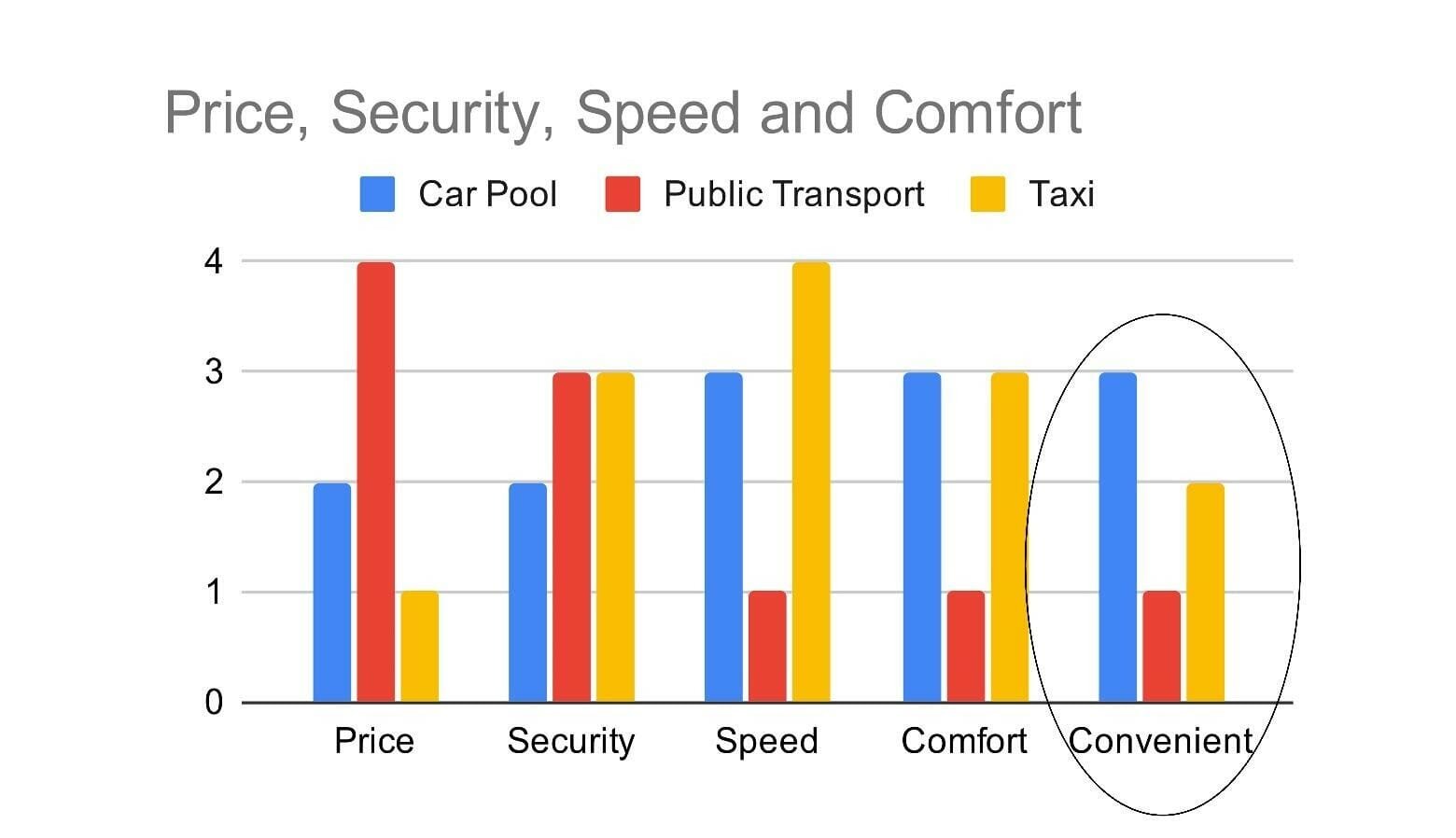

When you consider your offering’s characteristics and benchmark them against other players, you will be able to identify your core value differentiation. There are many benchmarking tools that you can use, such as Porter’s Five Forces analysis, but I suggest you keep it simple and use a chart to list the characteristics of the core offering.

Let’s review this with an example. Consider point-to-point transportation options in a city. We are focusing our comparison on public transportation, taxis, and carpool/rideshare services such as Uber. Among the characteristics most valued by passengers, we find price, speed, security, comfort, and convenience.

If we are a carpooling company reviewing the benchmark results, we may say that:

- We will never beat public transport on price, but we may beat taxis.

- On the other hand, convenience is our salient value. We are far more convenient than public transport and even taxis (since there is no money handling, customers request the service from a mobile app, customers can view the driver’s score, and so on).

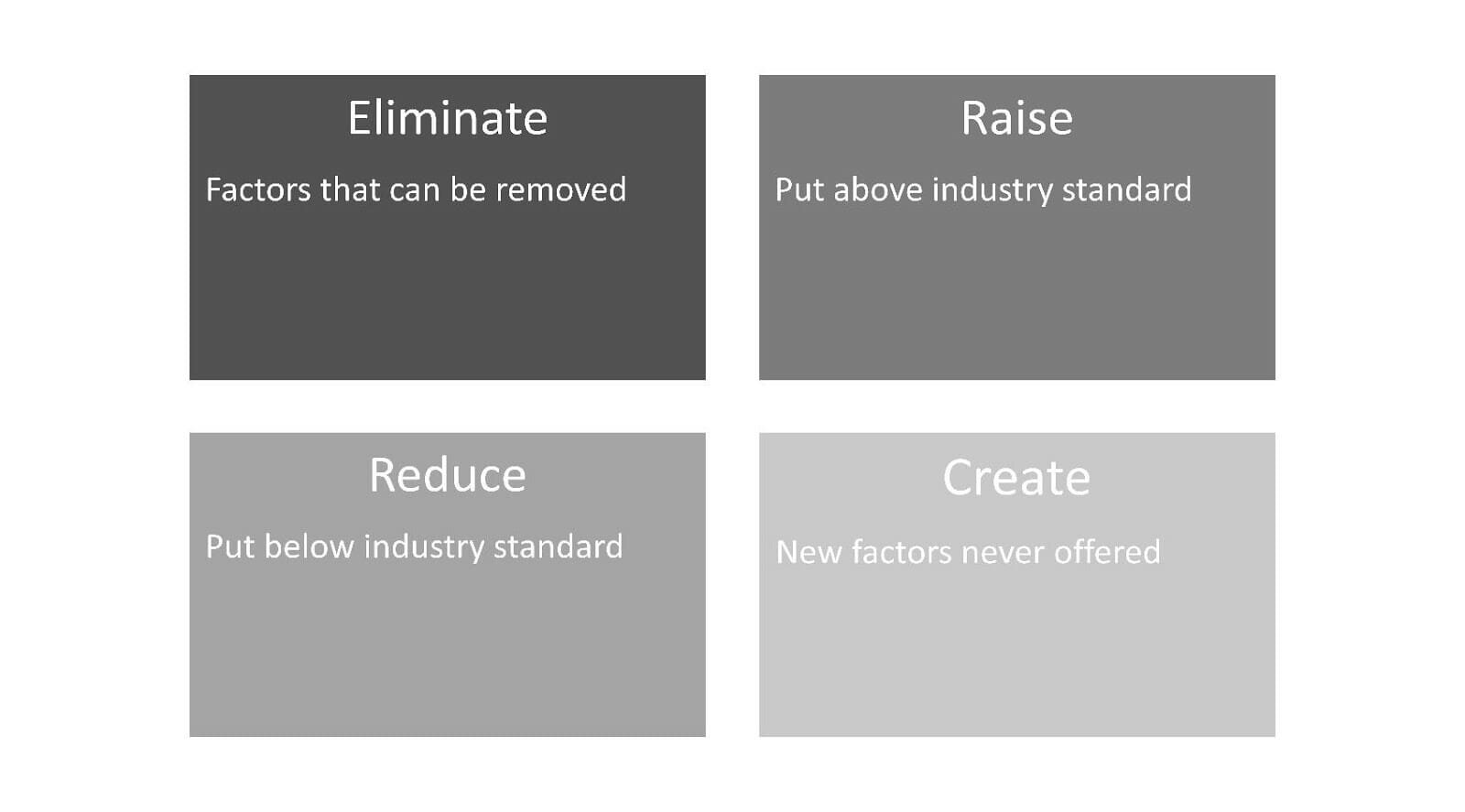

Once we have studied, the core attributes in this scenario, we can apply the technique ERRC (Eliminate, Reduce, Raise, Create) mentioned in the book Blue Ocean Strategy4 to decide on which factors to focus, as seen in Figure 1.4.3.

Using our transportation example:

- Should we focus on improving and consolidating the convenience differentiator?

- Or perhaps it would be better to concentrate on leveling some other aspects where we are less attractive to customers than the competing options, such as security?

Remember the low-cost airlines example previously mentioned? They decided not to compete on comfort and will probably never be attractive to passengers looking for that type of full-service offering. But by drastically reducing the comfort option, they cut costs and built a competitive advantage around fares, which is the highest valued factor for most travelers.

Insights Tool 2: Top of opportunity solution tree or impact mapping

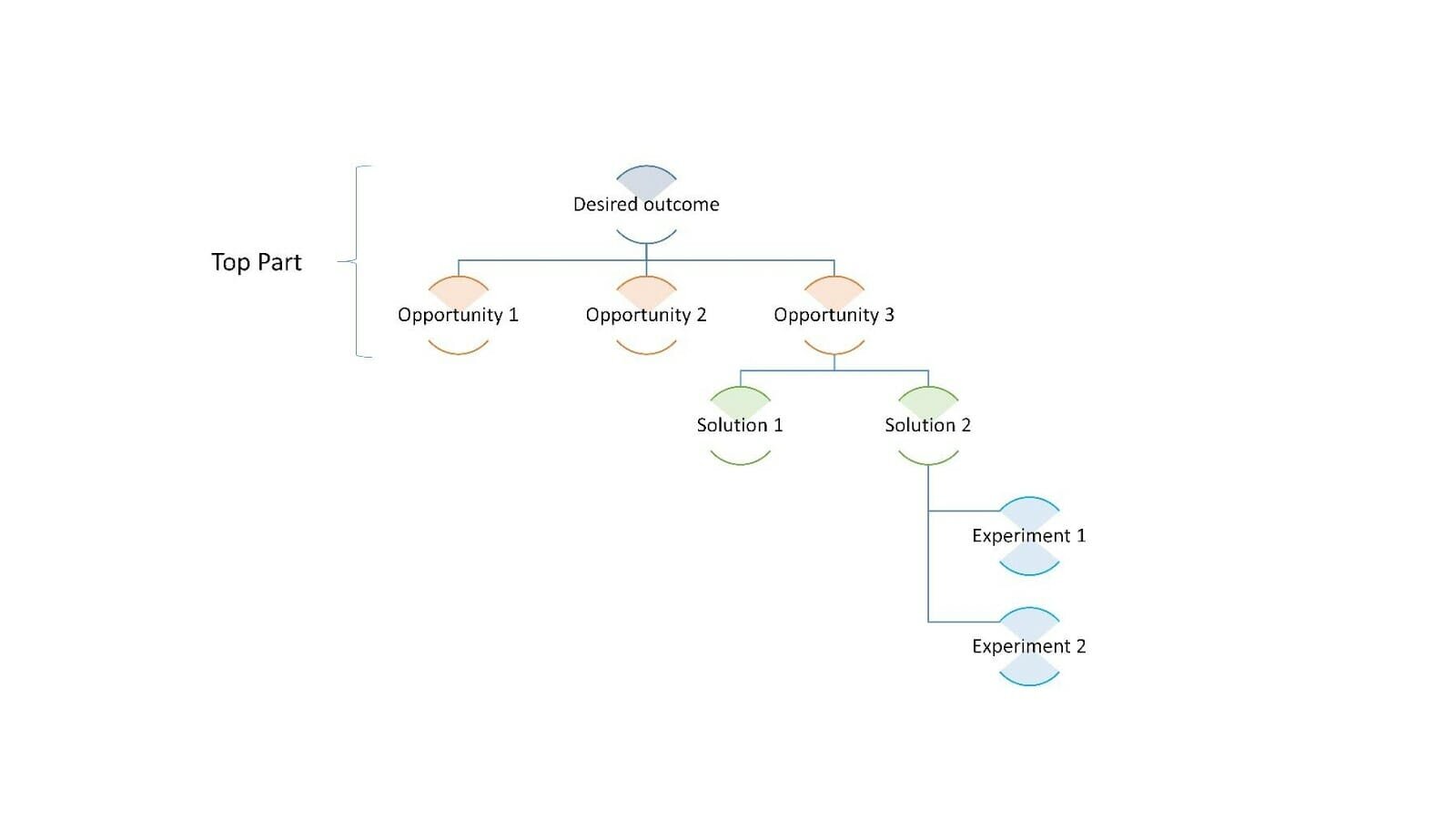

The opportunity solution tree created by the Product Discovery coach Teresa Torres5 helps organize discovery options and consider multiple alternatives for each desired outcome. While it was not created to be a strategy tool, it can help you consider multiple paths. Similarly, the initial steps of the impact mapping technique6 help you visualize how opportunities link to goals and actors within your product portfolio and will let you explore potential alternatives to achieve the same results. I will continue the section using the tree, but the result will be similar if you are more comfortable using impact maps.

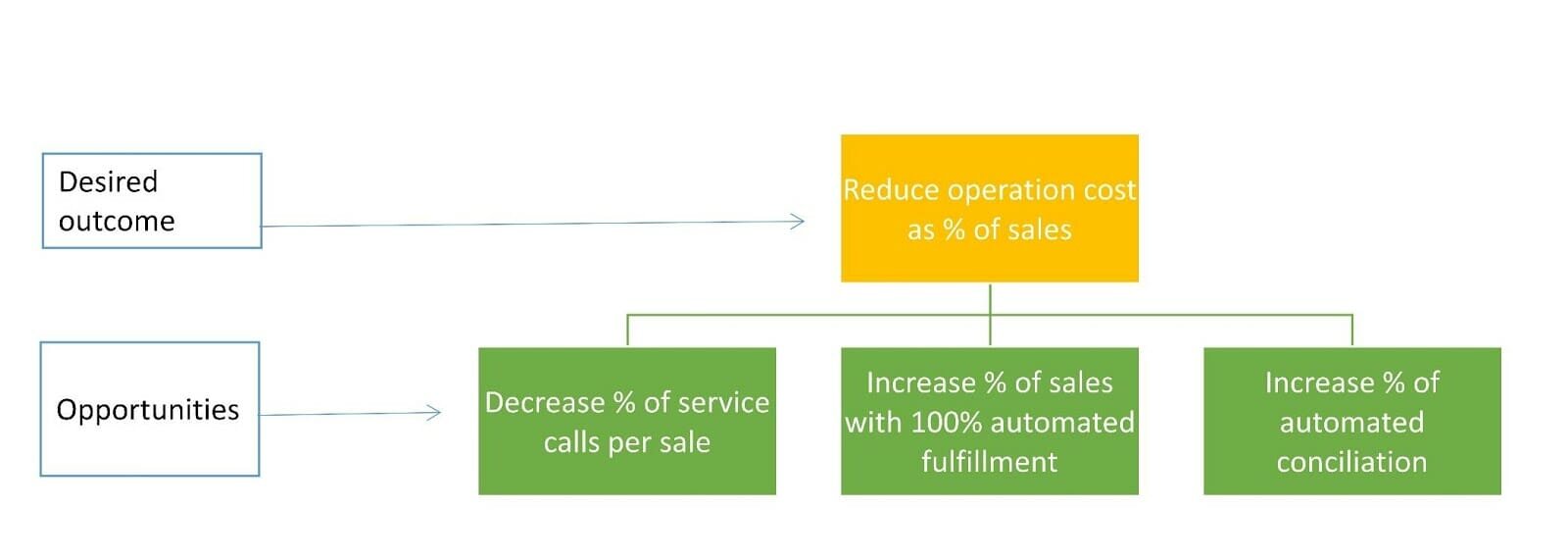

To start, define the desired outcome and use it as the root node of the tree. You can use the company’s high-level goal or list a number of your preferred outcomes since you are trying to explore many directions at this moment. Then for each outcome, you will create multiple “opportunities” nodes considering all the options that will move you toward that result. Those are the expected insights, as seen in Figure 1.4.4.

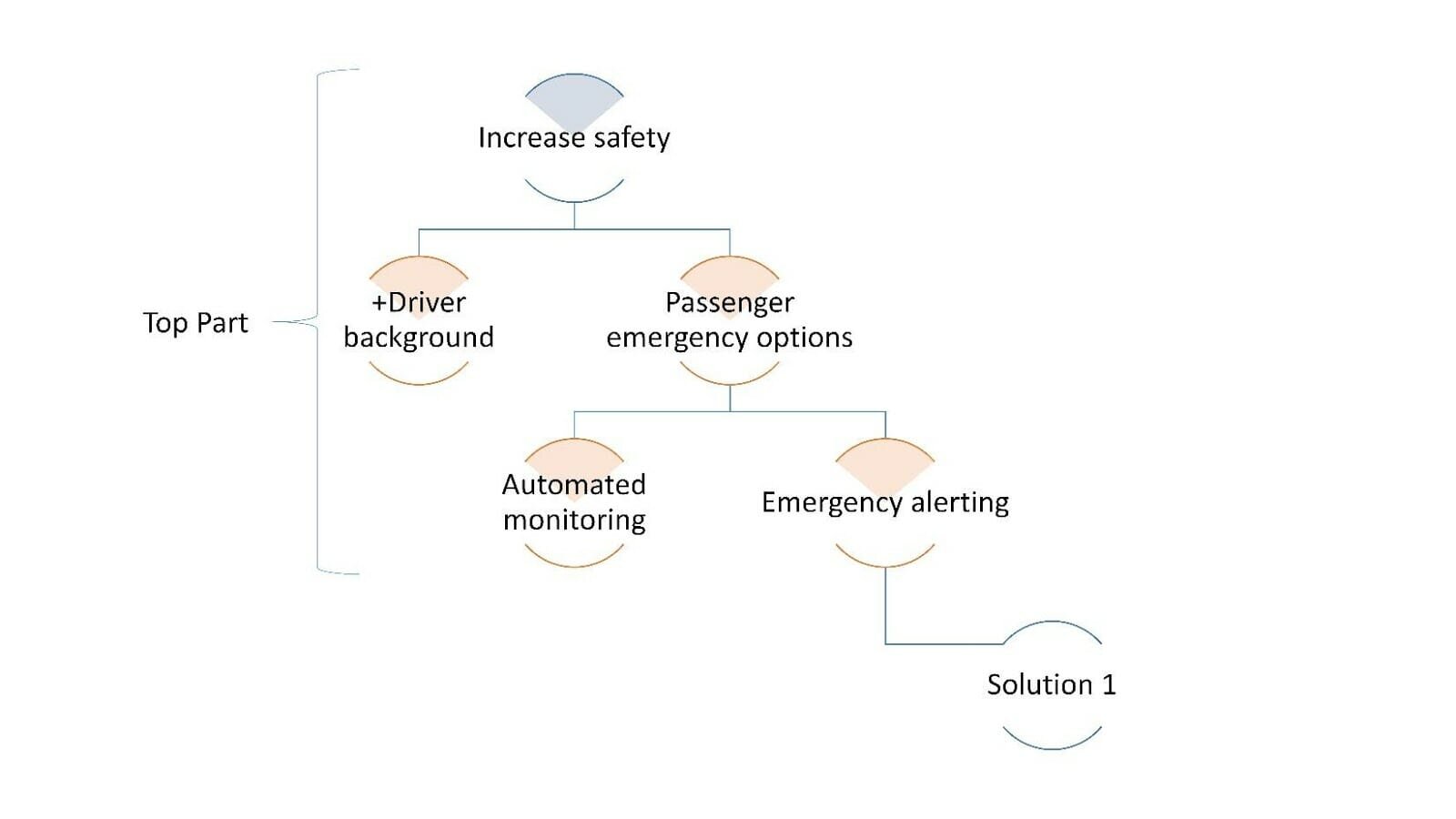

Hopefully, you will have many insights, and you can use the tree to group them, creating layers, or a hierarchy, of opportunities (see Figure 1.4.5). Going back to the rideshare example, if we consider the desired outcome of “Increasing security,” we can list high-level opportunities like “Increase drivers background information,” “Share your location,” and “Increase passenger tools for emergencies.” We might include “Increase automated monitoring” and “Emergency alerting” as lower-level opportunities for passenger emergencies.

The tool’s real value comes after we have defined our desired outcomes and identified the initial opportunities. What will often happen without using a tool like this is that we fail to consider further options and grab the first one we come up with. By forcing ourselves to consider other alternatives for the same outcomes, we are likely to identify a wider range of opportunities and find alternative and unexpectedly attractive paths to the outcome. We may also add resilience to our strategy, with alternative routes to solve a problem, if we find our plans fail to deliver when we begin implementing them. As an additional benefit of using it, you are introducing a tool that will quickly add value to teams during later discovery work.

Insights Iteration

As said, this process isn’t linear. When working on insights, you will need to go back many times and revisit your data and go deeper into the analysis.

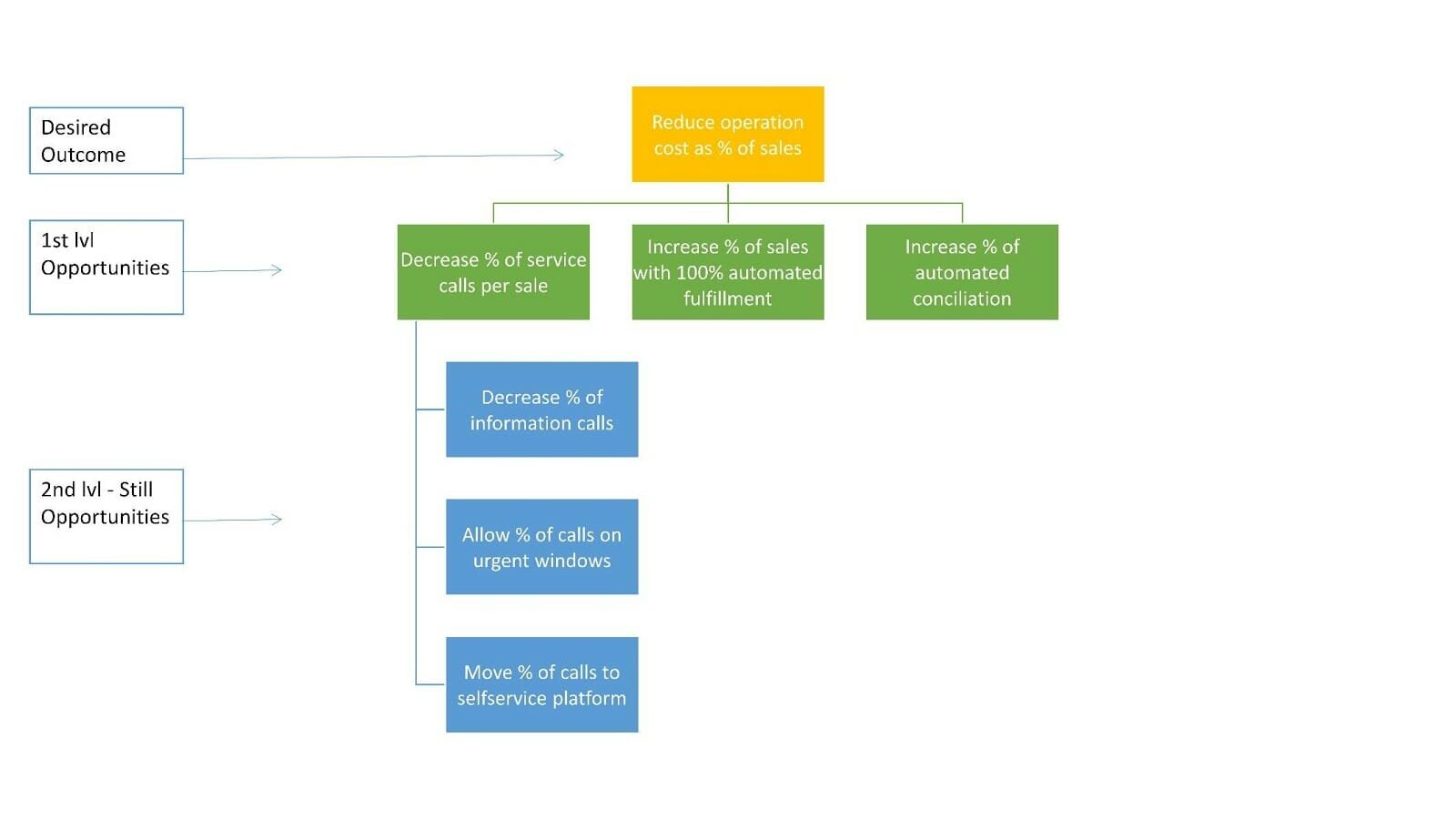

Let me use an example to explain. A few years ago, when we started the strategy process, we created the top part of an opportunity solution tree, listing our desired outcomes and the opportunities we identified. We had two critical desired results: increasing customer satisfaction (currently measured in Net Promoter Score) and reducing operation cost as a percentage of sales (we were not achieving profitable growth due to highly manual and time-consuming operations).

A few data points helped us identify opportunities that were outliers for that last option:

- The ratio of service calls per sale was higher than one, meaning that every customer called us at least once after buying a service.

- The number of sales that were automatically fulfilled was around 80%, below the industry standards.

- Due to some complexities and suboptimal implementations, the accounting department was manually conciliating more than 25% of service payments.

Armed with this initial landscape, we went back to dig for more detailed information that helped us identify insights one step lower.

Taking the number of service calls, we identified that:

- 70% of calls were to request information, way above the industry benchmark.

- A high volume of calls was done a long time in advance of using the service, resulting in more calls later from the same customers.

- Virtually no customers were using self-service post-sales options, and we had a very limited capability to move customers from phone calls to online service requests. The industry benchmark was around 50% self-service.

That information resulted in several clear and narrow directions from which to select:

In summary, this mapping activity is not an entirely linear process, and you should not expect to get through all of it in a single sitting.

Another well-known model by McKinsey and Company is the horizons of growth, which will help you analyze insights for different time frames. In the context of a company mostly dependent on digital products for its revenue, the product team is responsible for creating future income streams. This tool helps you visualize the current opportunities and the emerging ones that you can experiment with for future growth.

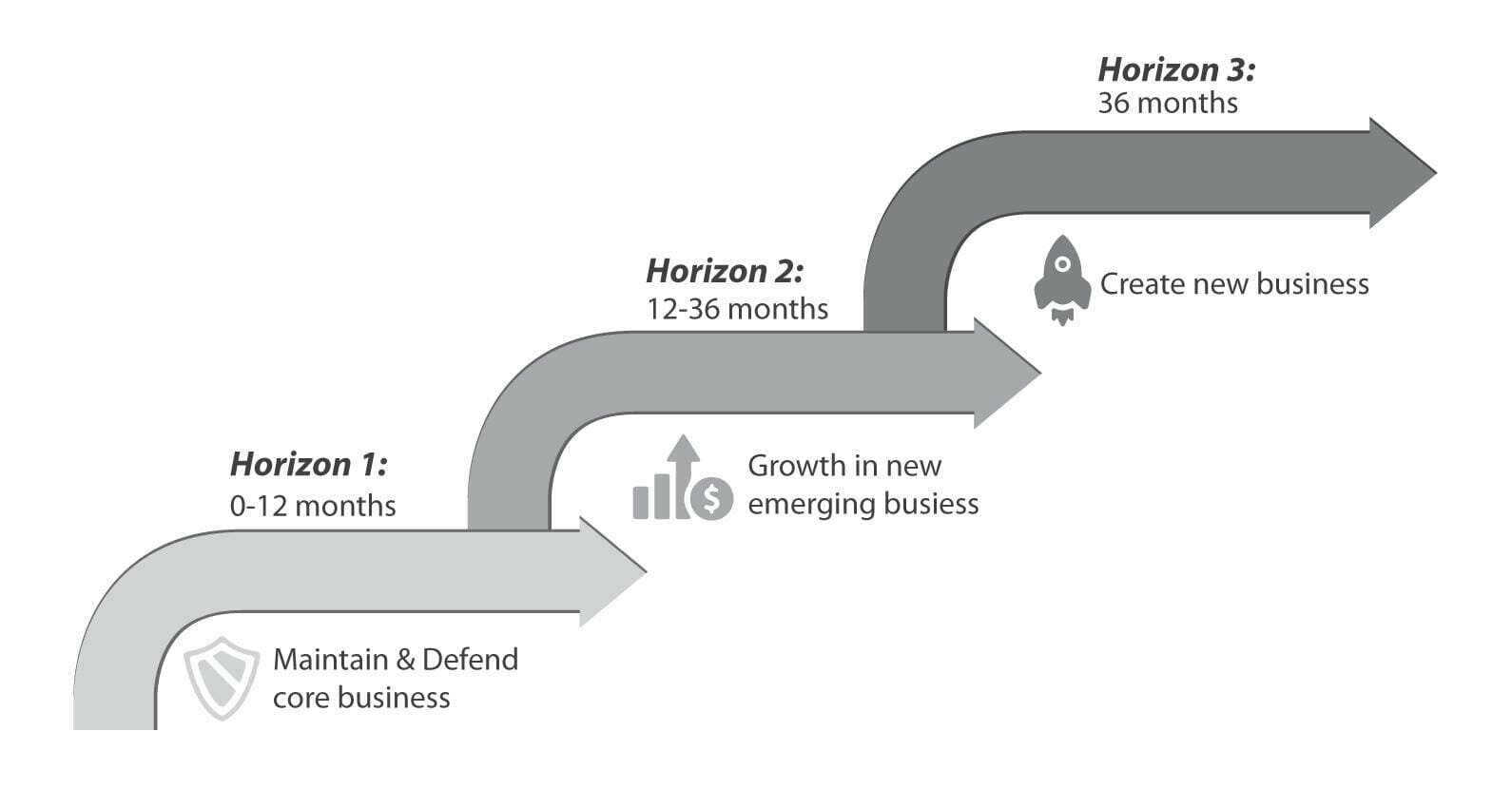

Insights tool 3: The three horizons of growth — McKinsey7

McKinsey’s framework divides your ideas as follows:

- Horizon 1: Insights focused on preserving the current business, with an earnings horizon of 0 to 12 months.

- Horizon 2: What can we do to expand to adjacent and emerging new businesses that will be the source of earnings in 12 to 36 months?

- Horizon 3: Disruptive future bets. Those ideas with the potential for creating new reliable businesses in three years or more.

As with the previous tool, drawing the horizons onto a whiteboard and organizing your opportunities in the three boxes will help you visualize whether you cover all of them and whether your focus is correctly spread. At the end of the definition process, your strategy should clearly articulate what you are doing for horizons 2 and 3.

Note: This method would be more useful for mature companies. Young startups may be more focused on survival and short-term growth.

Insights with other models and canvases

The three tools mentioned are my go-to methods when starting from scratch. But there are many more popular tools that are valuable to identify insights, and you should leverage them if they are suitable for your expertise and context. A few examples are:

- The Kano Model: This is a very popular framework to categorize functionality, according to the customer satisfaction they produce, into must-have, performance (the more, the better), and delighters. Similar to the ERRC tool, consider comparing your current solution to competitors to identify opportunities.

- Other “legacy” tools: SWOT analysis, BCG Matrix, Porter’s 5 forces, McKinsey 7S Framework, are examples of strategy tools used in the 80s and 90s. They are a bit outdated and considered oversimplified for today’s world, but are still powerful models to think about your strategic positioning. For instance, by thinking through Porter’s 5 forces lenses, you may identify insights such as a high dependency on Google Ads for customer acquisition and decide to mix it with an opportunity solution tree with alternative opportunities to diversify your channels.

- Two more particularly useful canvases are the Business Model Canvas and Value Proposition Canvas, both created by Strategyzer.8

I cannot include these last two as part of any particular step in the strategy definition process because they are useful in many areas. For example, they can help you:

- define your vision, creating the canvas of your desired future.

- identify insights by using canvases of your current state and detecting options for improvement.

- define and communicate your strategy by drawing your “next year” canvases.

- direct your discovery by finding your riskiest hypothesis in your entire plan.

In summary, I would recommend using these canvases, starting at the vision level and keeping them updated for communication purposes as you progress with the strategy definition.

Insights session

The tools we have mentioned can either be used for asynchronous collaboration (in other words, people complete them individually or in small groups, offline) or be completed in a team session. Considering the collaborative and interdisciplinary nature of this work, if you can come up with a manageable team size, the best option is to have an “insight workshop.”

Before the meeting, provide an introduction to the techniques you will be using, and make it a requirement that all participants come prepared to share the insights they may have already been thinking about.

Try to use silent brainstorming (inviting users to post sticky notes in silence before you discuss the output) or other methods that will allow for collaboration in big groups without discouraging any ideas. Use a few rounds to enable people to build on top of each other’s insights. If your team size is too large, you can break into smaller groups.

The essential part of the workshop is affinity mapping: different people will very likely identify the same opportunity using different words. Group the contributions by theme to make later selection easier.

If having a workshop is not possible, and you choose to work offline, keep in mind the challenge that will come later when participants need to gain a shared understanding of the different opportunities. Everyone will have to explain their point, and you will need to consolidate the ideas before you start any selection.

Connecting your vision and target customers to the insights

So far, we have not been very specific on how the vision and the customer segments relate to the strategy. The core connection will occur in the next chapter, where we will select those opportunities that strongly correlate with our desired outcomes. When considering insights, you want to take a broad view of your vision and target customers in order to make the process manageable without getting lost in the details.

Expected Output

By the end of the insights step, we should have:

- A “wall of insights”: Fundamentally, we are trying to create a big list of insights to decide from. Capture them in sticky notes, spreadsheets, or any supporting tool your teams prefer.

- Organized insights: Using the available tools, you have grouped insights into categories, desired outcomes, time horizons, and whatever classification seems useful for later selection.

- Shared understanding: Team members should have the same idea of what each insight refers to.

Keep in mind that this is not a “complete it and forget it” step. You will need to iterate it many times, chasing findings that lead to more investigation and deeper insights. Insights are a constant part of discovery, feeding back to the strategy process as your execution progresses.

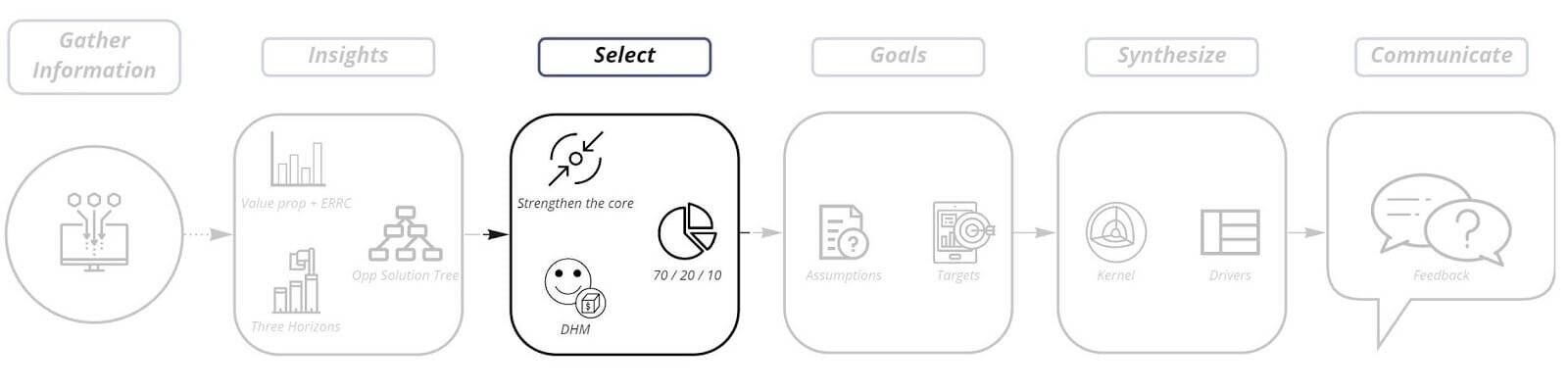

Chapter 1.5 – Step 2: Select

“Good strategy works by focusing energy and resources on one, or a very few, pivotal objectives whose accomplishment will lead to a cascade of favorable outcomes.” Richard Rumelt, Good Strategy Bad Strategy

In 1998 a young Netflix was selling and renting DVDs by mail. A growing Amazon, looking to expand its retail footprint, considered acquiring Netflix to jumpstart their own DVD business. While they did not reach an agreement, Netflix’s CEO realized that they would never compete in the long-term selling DVDs. They were confusing customers with a dual value proposition and being distracted from the renting side of the business in which they were building a really unique model and competitive advantage. They decided to kill the DVD selling side of the business to focus on renting. At that time, selling DVDs made up more than 90% of their revenues.9

Selecting is about focusing on the most promising strategic drivers and understanding the necessary tradeoffs of pursuing them.

What is expected from this step?

- Decide which few insights can have the most substantial impact on your results.

- Understand how they interact together.

- Align the selection with the resources available.

While the previous step was crucial to identify true potential and avoid following mindless hunches, this phase is the essence of the alignment toward the desired course of action.

Keep in mind that selecting is about focus and positioning. We want to align the entire organization to the differentiation we wish to have on our customers’ value proposition, based on the insights and opportunities detected. It is not just about prioritizing the options; it also requires a high-level definition of goals, as well as of the chosen path’s assumptions and risks.

Considering positioning

Let’s reflect on the example of companies trying to sell at-destination activities for tourists (for example, city bus tours). Your team may present you with a whole range of opportunities, but, depending on your circumstances and the long-term plan, your first task is to decide what problem you want to solve and how you want to be seen by customers. For example:

- Do you want to be the company with the largest selection of options?

- Or perhaps you want to have a limited set of genuinely unique experiences.

Both paths may offer great potential rewards, and you may have plenty of options for each of them. Unfortunately, they are incompatible. If you select a few ideas from each path based on their potential revenues, you will end up with a mediocre value proposition for both. You need to commit to a strategy and then select the best ideas for that strategy, even though this involves deliberately leaving some great options unrealized.

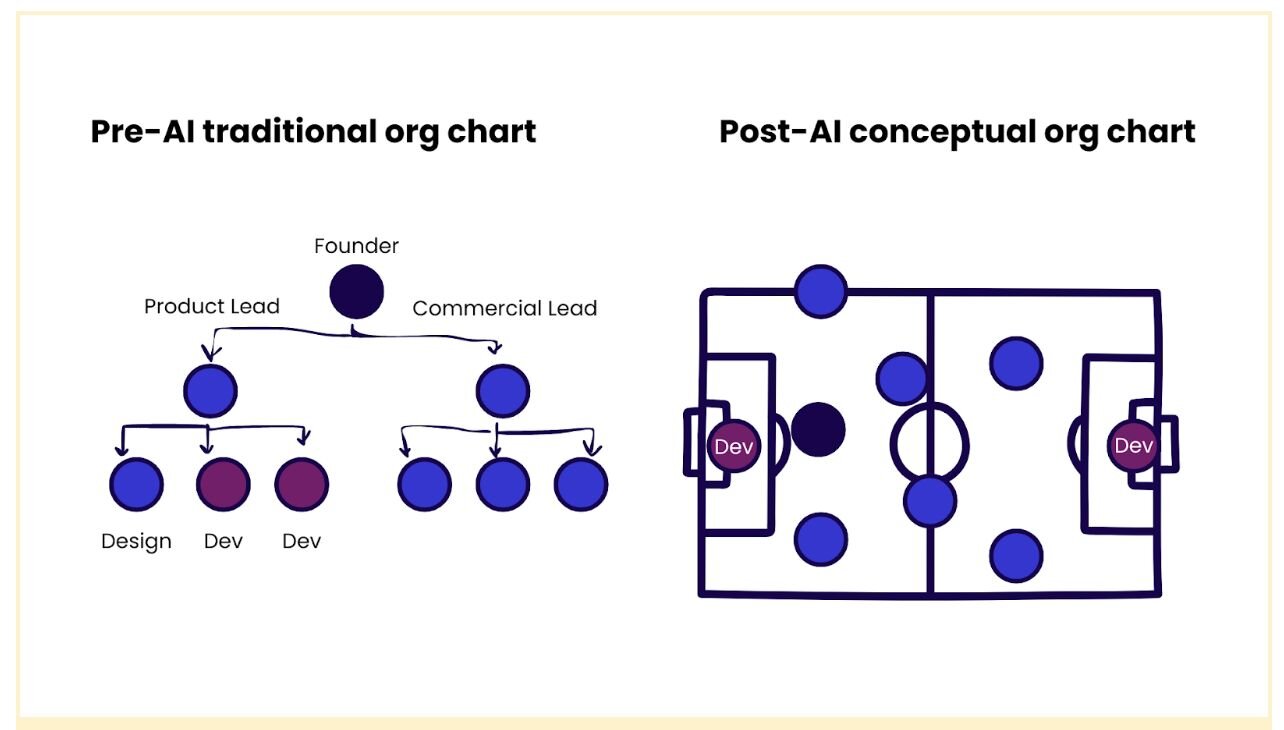

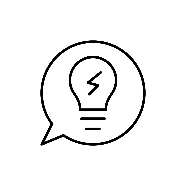

High-Level company goal

As said, it’s likely the company will have some basic goals already decided. During insights, that focus was not critical. We wanted to explore many paths to establish whether we could be overlooking a big opportunity.

Now during selection, the company’s focus gains more relevance. Essentially, it will reduce the number of options by pre-filtering those that are worth considering because they align with your declared objectives (see Figure 1.5.1).

Keep in mind that there are two other possible scenarios:

- The company may not have a clearly defined path. This is not necessarily a bad thing. Product leadership may play a higher role in determining the overall company’s positioning, especially in smaller, product-led companies.

- A sharp insight may highlight a valuable opportunity that appears to conflict with the high-level goal. Consider a scenario in which geographic expansion is not an intended goal, but you have received many organic customer requests to make your product available in other regions. This kind of customer-driven insight may become a relevant game-changer for the company. Faced with this scenario, product leaders are responsible for raising this issue with the CEO and other stakeholders and work with them to decide if the high-level goal should be modified.

Selecting to Win

In the book Playing to Win,10 the authors argue that if you do not decide on a strategy for winning, you will fail to make the resource investments and commitments required to become the leader in your segment. They use the example of the Saturn car created by General Motors as a separate brand in the 80s. GM’s goal was to preserve some of the low-end markets that Japanese brands were gaining, but they never considered the Saturn a winning move to dominate that segment. Since they were not planning to win, they were always only half-hearted with their commitment, resulting in a mediocre product and low market share.

A winning mindset is crucial during the selection step. You do not need to become a world leader brand or have the largest share in an entire industry. But you do need to select a strategy that will enable you to dominate a niche market or compete based on a key attribute that customers value highly.

Consider the streaming service “ScreamBox,”11 with its offering “Discover horror you won’t find anywhere else.” They may not be comparing themselves to Netflix in terms of subscribers or streaming industry share. But they want to be the #1 service for horror film lovers, and they will compare how many clients in that segment are opting for alternative streaming platforms to view this category of movies.

Tools for Selection

Enough theory! Let’s start selecting. Most of the time, this is an important, potentially complex decision process, so I suggest a few tools to improve your result.

Previous Strategy and Insight tools

Remember, it is likely that the company is already executing a strategy based on the desired mission and end goal. The current path will provide strong input for the new selection.

Additionally, you can work on top of the already used insight generation tools. Pruning an opportunity solution tree, or completing a value proposition canvas, can be an excellent complement to the tools we will see in the following sections.

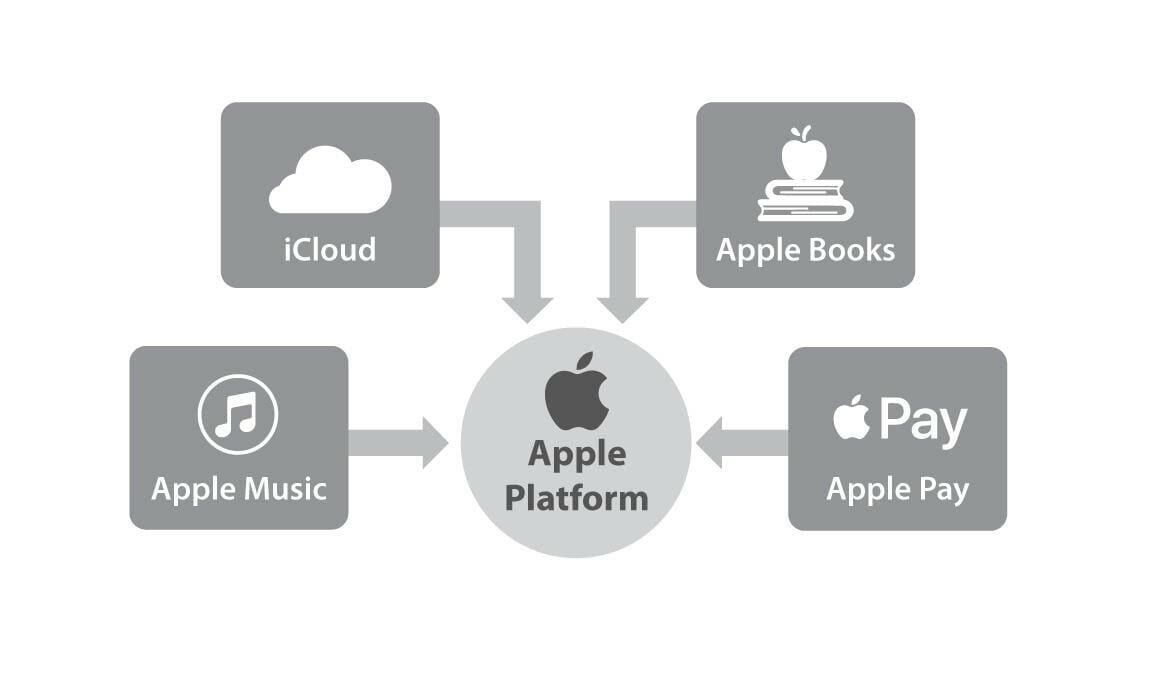

Selection Tool 1: Strengthen the core

I consider this to be the most useful selection tool, albeit a relatively unknown one.12

The idea is to select and group those insights that enhance your current core business and value proposition.

A clear example is the Apple ecosystem. When Apple created services like Apple Music, Apple Books, iCloud, and so on, it also strengthened the sales of their devices and their use (in 2019, Apple was generating more revenue in services than in Mac, iPad, or wearables). For example, by automatically storing your iPhone photos in iCloud, Apple made the phone more valuable to their users by enabling automatic backups, the ability to share with other iPhone users easily, and syncing their photo library with other devices like their iPad.

Consider the opposite example: manufacturing companies’ products are usually standalone. Consider Samsung, for instance: they produce smartphones, computers, TVs, cameras, printers. While there may be minor interactions, I haven’t heard of anyone buying a Samsung laptop because they had a Samsung smartphone (and compare that to people you know using Mac and iPhone for their connectivity).

This approach to selection can also be related to what Professor Rumelt mentions in Chapter 13, “Using Dynamics,” as harnessing a position of advantage.13 Strategic advantages are hard to achieve. Once achieved, leaders must focus resources to strengthen the position, further differentiate the unique value they provide to their users, and exploit their potential.

Evolving competitive advantages

Strengthening the core also is about building and enhancing advantages. To keep winning, we need to understand that yesterday’s superiority will become tomorrow’s commodity. That is why the core tool is so important: we are continually evolving our competitive advantage. We enhance the value we provide to users while making it harder for competitors to outperform our value proposition.

Amazon is another excellent example of this continuous pursuit of value and strength: increased sales and economies of scale allow for better prices, faster delivery, broader product selection (sellers programs), increased value for Prime members, devices to enable new selling channels (Alexa). And they keep innovating to strengthen their core marketplace experience, making it more valuable and reinforcing its advantage.

How to use it with your product or portfolio

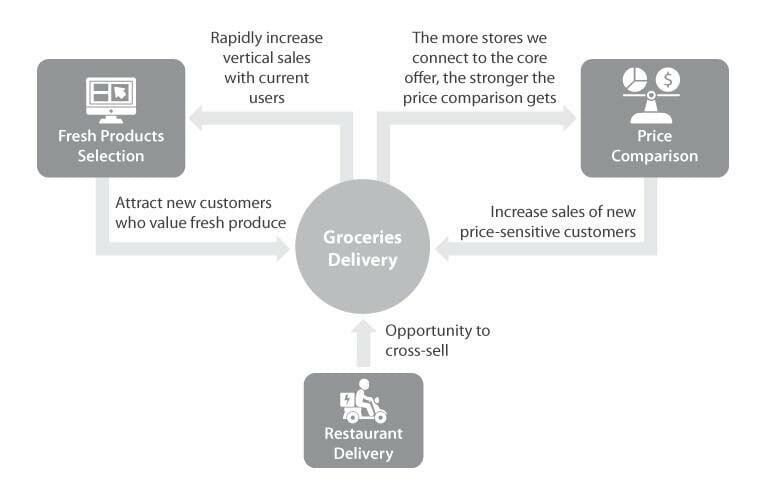

Write your core product offering in the middle of a whiteboard. Take the most valuable insights (or insights categories) and place them around the center. Draw a line from each insight to the center with a description of how it improves your primary offering. Likewise, draw a line back from the center toward the insight, explaining how your core value makes this opportunity more attractive and likely to succeed. Let’s look at the following example of a company that focuses on grocery delivery. They are considering three insights on which to focus, as seen in Figure 1.5.3.

In some ways, the link is a new form of discovery. You are learning how this opportunity will play out with your current model. For instance, the grocery team was thinking of resolving the price comparison problem between stores as a service to let people know where to shop. Including it as part of the core shopping experience may result in a total new positioning along the lines of “save while shopping from home.” And as the grocery business grows, adding more stores and products, the price comparison becomes even more valuable for users.

Once your diagram is ready, you can start removing any “orphan” insights you couldn’t connect to the product offering or for which the connections are weak. In our example, “adding restaurant delivery functionality” does not add a great deal of value to the current offering. It is a significant opportunity to pursue, but investing in it would divert resources from our core advantage.

The second type of selection you use depends on the desired outcome. For example, if you want to focus on retaining your current user base, it would be more valuable to prioritize the price comparison space. If, instead, you want to expand to new users, then resolving the fresh produce selection problem may attract customers interested solely in a service that you do not currently have while adding value to your existing base.

Repositioning your core

Another use of this tool may be to reposition your offering and understand what insights are the most appropriate for that purpose.

Let’s revisit the grocery example. The company’s vision is to solve all transportation needs that require complex interaction with the store providing the service. The initial strategy was to focus on groceries, and once they dominated that vertical’s experience, they could start expanding to others.

When you review the strategy, you may decide it’s a good time to make that expansion move. In which case, leaders will need to change the core definition, putting “Complex Delivery” at the center of the strategy instead of “Groceries Delivery.” Now insights such as restaurant delivery could assume greater relevance (and you may even consider new options based on this move).

Selection Tool 2: Google’s 70/20/10

Eric Schmidt presents the 70/20/10 tool in his book How Google Works.14 It represents the company’s formula for resource allocation: 70% to the core business, 20% on emerging opportunities (already proven and growing), 10% on new bets with a high risk of failure but a big payoff if they succeed.

Considering the “core, emerging, new” concepts, the tool resembles McKinsey’s horizons of growth, going a step further and suggesting how to select insights based on effort and allocating them across the time frames.

While everyone in the company is responsible for ensuring the organization’s future success, the product team has an extra duty. They need to experiment continually and expand the product for future growth. Whether you use the tool or not, your selection should reflect that you are investing in experiments expected to drive future revenues.

Number of experiments outside your core business

There is an important consideration for the 20% and 10% allocations. You want to be able to test multiple ideas. Considering that these are risky bets, you should expect many of them to fail. Innovation does not depend on thorough analysis during selection, but rather on the number of learnings from the experiments you can run with those high potential opportunities.

The extent to which you can experiment will depend on your size: an allocation of 10% for Google is radically different from 10% for a startup. On the other hand, Google needs to create a far larger stream of revenues for the future, so they need to make many bets and find multiple winners. In the early 2000s, for instance, the company was experimenting with Gmail (2004), Maps (2005), Google Analytics (2005), AdSense (2003), Picasa (2002), and many more.

If you are not using the 70/20/10 method, or want to explore other alternatives to innovate outside your core, consider options like 3Ms 15% program15 (replicated by many companies later), hackathons, or any other scheme that will enable teams to test ideas that are not aligned with your core strategy, giving you input for future development.

Selection Tool 3: Gibson’s DHM framework

Gibson Biddle16 provides one of my favorite definitions of what product leaders ought to be doing:

- to delight customers (1)

- in margin enhancing (2)

- and hard to copy (3) ways.

In line with that definition, he created the DHM model, which proposes analyzing each opportunity through the lenses of these three characteristics.

Using this diagnosis requires a number of hypotheses and assumptions about how your solution will pan out, but in this case, many options are easy to evaluate. For example, consider improving the landing page of a Software as a Service (SaaS) product to improve subscriptions. It will probably enhance your margin (if so, you should definitely try it), but it is hardly a feature to “delight” customers, and it is easy to copy.

How to use the tool with your product or portfolio

Simply create a table with your more promising opportunities and columns for each of the three criteria. Mark each insight as: 1. The ability to delight customers; 2. Enhance margins; 3. Hard to copy. Focus on selecting those options that carry ticks in all three columns!

Creating a strategy without these attributes may jeopardize the future of your product. So if you don’t have any opportunities representing all three, I suggest going back to the insights board and keep analyzing more options.

Alignment Filter

We are done with tools! Whether using them or not, by this time, you should have selected your most promising problems to solve, such as “Solve the fresh products selection problem,” from the delivery example above. During the selection process, you should keep in mind that you are looking for a cohesive strategy that aligns the company toward a particular positioning.

Now is the time to double-check your work. Are the selected options compatible? Do they all point in the same direction?

Let’s consider a mature retail e-commerce company focused on streamlining and automating processes to increase margins. Given the size of their strategic opportunity, they have also included expansion to the home-repairs category as part of the strategy. While at first glance this seems innocuous, when they reflect on the implications for how the company will deliver the new service, they realize it will require a lot of new and radically different processes and probably manual steps, at least until they understand how to automate them.

This dissonance is precisely the kind of thing we are trying to avoid. Imagine the home-repairs team, who is working to implement and grow the service, talking with the operations team to create a new process that will have a number of manual steps. The Ops team is pursuing the goal of reducing procedures and eliminating manual steps, which runs completely counter to what they are being asked to do by their colleagues.

While it is far better to avoid it, you can do it if the opportunity justifies the effort. But keep in mind that:

- You should communicate the inconsistency. The goal should read something like “automate all processes, except those required for the new services category” (making the conflict visible).

- Having this kind of exception complicates strategy communication, and it will require greater management team involvement to “clarify” potential misunderstandings.

Expected Output

By the end of the selection step, we should have:

- A list of selected problems or opportunities on which to work.

- Determined each element’s correct interaction and alignment (or recorded any exception).

- Clearly defined expected time horizons for each opportunity.

Now You’ve Started…

Buy Product Direction and and finish this great read — complete the book to discover the tools and techniques you need to go through the creation of a product strategy, a strategic roadmap, and OKRs.

See Nacho at #mtpcon Americas

We’re taking our San Francisco conference online again this summer on 14-15th July and we can’t wait to come together to push our product craft forward. Nacho will be joining our line up of amazing speaker to give an interactive session. Find out more and book your ticket today!

References

[1] Product discovery is the stage of the product development process where we apply tools and techniques to understand the problem and define the best possible solution.

[2]Drucker, Peter F. (1985). Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Harpers Collins.

[3]Keeley, Larry (2013). 10 Types of Innovation. Wiley.

[4]Kim, W. Chan (2004). Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make Competition Irrelevant. Harvard Business Review Press.

[5] Torres, Teresa. “Why This Opportunity Solution Tree is Changing the Way Product Teams Work.” Product Talk, 2016. www.producttalk.org/2016/08/opportunity-solution-tree/

[6] Adzic, Gojko (2012). Impact Mapping: Making a Big Impact with Software Products and Projects. Provoking Thoughts.

[7] McKinsey. “Enduring Ideas: The three horizons of growth.” McKinsey Insights, 2009. www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/enduring-ideas-the-three-horizons-of-growth

[8] Both tools can be reviewed and downloaded for free at https://www.strategyzer.com/canvas.

[9] This story is part of “That Will Never Work”: Randolph, Marc. 2019. That Will Never Work: The Birth of Netflix and the Amazing Life of an Idea. Little, Brown and Company.

[10]Lafley, A. G.Martin, Roger L. (2013). Playing to Win: How strategy really works. Harvard Business Review Press.

[11] More information in https://www.screambox.com/.

[12] I first heard of Remi Guyot’s tool this tool from Remi Guyot from BlaBlaCar, but I haven’t found any reliable source to reference it.

[13] In the already cited Good Strategy Bad Strategy book.

[14]Schmidt, Eric (2014). How Google Works. John Murray

[15] Goetz, Kaomi. How 3M Gave Everyone Days Off and Created an Innovation Dynamo. FastCompany, 2011. https://www.fastcompany.com/1663137/how-3m-gave-everyone-days-off-and-created-an-innovation-dynamo

[16] Biddle, Gibson. #2 From DHM to Product Strategy. Medium, 2019. medium.com/@gibsonbiddle/2-from-dhm-to-product-strategy-a3781b2aadca