What surprised me was the attention my book received from managers of large and well-established corporations, too. The leaders of business behemoths like Pepsico and Walmart were calling and writing to pepper me with questions about how OKRs could transform their companies also. Could the OKR approach, they wanted to know, be scaled up to their own organizational level?

I was happy to answer them: Long-term strategic planning is tricky, as life is always throwing shiny objects at you. But well-set OKRs will act as effective guideposts to success for organizations of any size. In the following excerpt from Radical Focus 2.0, I outline the best strategies for setting and scheduling organizational OKRs in a way that won’t lock teams into outdated game plans.

OKRs really do work for anyone trying to do more than just conduct business as usual. Hopefully, this post will inspire you and your team to set challenging and achievable goals to build success for your organization.

Note: TeaBee, the second company referenced in our example, is the tea company discussed earlier in the book’s story.

Enter the Cone of Uncertainty

An excerpt from Radical Focus (second edition). All rights reserved.

You have a mission. Check.

You have a strategy you wish to pursue. Check.

You have an annual OKR set or have decided not to have one. Check.

Now the exec team sets four Objectives and three Key Results: the first quarter Objective with its accompanying Key Results and then three more candidate Objectives for the other three quarters, but no Key Results for them. I recommend this approach for two reasons: one, setting Key Results takes quite a bit of time, and two, it’s hard to predict future organizational needs. In 1958, J.M. Gorey used the term the cone of uncertainty. This model states that the farther we predict into the future, the less accurate our predictions become. However, without a long-term goal, it’s hard to make long-term plans and move from reactive to strategic. We solve this by having specific goals for the near future, and lightweight drafts for the less knowable far future.

Half-Built Strategy

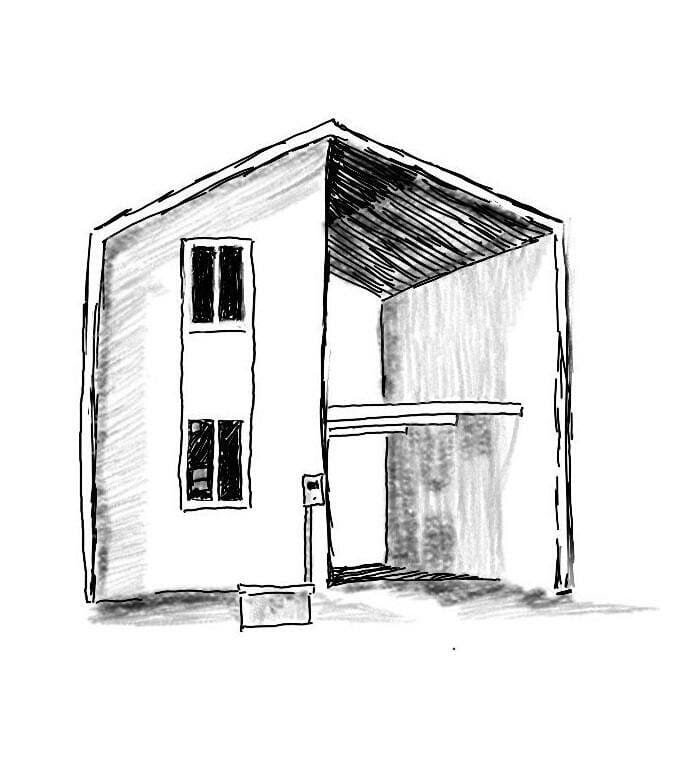

In 2010, Constitución, Chile had a massive earthquake. It left more than five hundred people dead and about 80 percent of Constitución’s buildings ruined.

An architecture firm called Elemental was hired to create a master plan for the city, which included new housing for people displaced in the disaster. Elemental decided to give people half of a house.

The houses are simple, two-story homes, each with a wall that runs down the middle, splitting the house in two. One side of the house is ready to be moved into. The other side is just a frame around empty space, waiting to be built out by the occupant.

What do half-built houses have to do with OKRs? They are an inspiration for what I call a “Half-Built Strategy.”

A Half-Built Strategy follows the cone of uncertainty’s warning about predictions. You create a complete OKR set for the next quarter. Let’s call that Q1, as it often is. You have the Objectives and three or so Key Results pinned down. You feel confident entering this quarter that your OKR set is difficult but not impossible.

But can we create an OKR set for Q2-4? Probably not, as we need to see how Q1 goes first. But rather than just hand wave at plans for the future, we can put in three draft Objectives for the next three quarters.

Why don’t we have Key Results? As I’ve taught people the OKR methodology, I find that Key Results are often harder to set than the Objective. They take a fair bit of time as you discuss which metrics matter and if you can access them. The longer you work on something, the more precious it is to you. (This is called the Ikea Effect, if you want to look it up!) So by making the Half-Built Strategy four Os and three KRs (all for Q1), we still have a North Star to work toward, but it was made quickly, so the team doesn’t feel they wasted time making an unusable plan. They’ll be more willing to evolve the plan as more data is collected each quarter.

Deliberate building in of strategy absence may promote flexibility in an organization… . Organizations with tight controls, high reliance on formalized procedures, and a passion for consistency may lose the ability to experiment and innovate.

— Andrew Inkpen and Nandan Choudhury, “The seeking of strategy where it is not: Towards a theory of strategy absence”

Let’s look at how this plays out in real life. Let’s say that there is a start-up that is going to have to start raising their B-round in Q1 2018 and it is now the end of Q4 2016. I’ll name this company TinkWorks, for convenience.

First you choose an annual OKR set. TinkWorks’ annual Objective is something about being ready to raise that B-round of investment. TinkWorks’ CEO will then choose an Objective each quarter that leads to the desired end state: showing traction in order to raise money.

We all know you don’t pour whiskey through a leaky funnel into a flask and hope to get drunk; you don’t want a dozen Objectives for the same reason. So TinkWorks’ clever CEO decides to theme each quarter. Q1 is all about retention, Q2 is all about conversion, and Q3 is about acquisition, and by Q4 she’ll be able to settle into pitch and roadshow prep.

Now that she has a loose Roadmap for the year, she settles in to wordsmith her Q1 Objective and pick the right Key Results with her executive team. She goes ahead and picks those with her team, and she’s done.

Choosing Key Results after the EOQ retrospective means that the next quarter’s OKRs will take the learning of the previous quarter into account. If there is a better metric to watch, for example, or something about the retention that will affect the conversion strategy, the KRs can reflect that correctly. Picking the right metric and calculating the right amount of growth is a lot of work. It’s best done just-in-time.

You want just enough planning to know what to do and what to watch for, but not so much you are locked into a bad game plan.

Appropriately sequenced Objectives also create institutional learning. Imagine a team spends a quarter thinking day and night about retention. The next quarter they are profoundly focused on conversion. Do you think their memory was wiped clean? No! Retention is now part of the company DNA. You can make retention a Health Metric if it needs continued monitoring.

What does this look like for [our example company] TeaBee?

Mission: Connect the best tea growers with the customers who love quirky and delicious tea.

Annual Objective: America looks forward to discovering new tea after a fine meal, thanks to TeaBee.

KR: Revenue of $20 million in more than five geolocations

KR: Aided brand awareness is up 10%

KR: 500 or more requests for TeaBee teas for home use

Q1: The west coast loves TeaBee

KR: $1 million revenue booked in L.A., Portland, and Seattle

KR: Five restaurants have “TeaBee served here” stickers in windows

KR: At least one early adopter has booked TeaBee deliveries through the year

Q2: New York loves TeaBee

Q3: Austin loves TeaBee

Q4: D.C. loves TeaBee

TeaBee now has the flexibility to change the Q2-4 OKRs as they learn from Q1, yet the idea that they are expanding via locations is clear to the company.

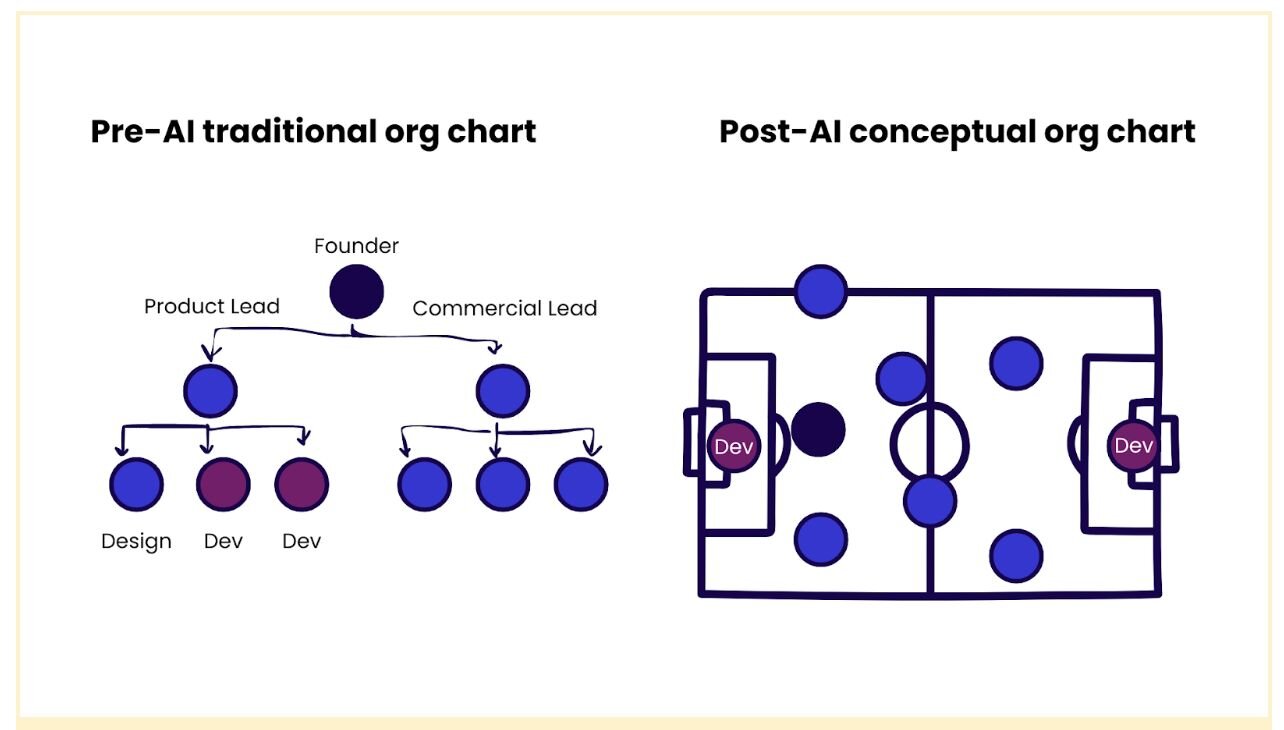

Next all self-sufficient teams can set their OKRs. These are autonomous, empowered teams that have all the resources they need to proceed. It’s often product teams that have dedicated design and engineering resources (and more, depending on your company type). These candidate OKRs can be reviewed and discussed with the direct manager of the teams. This “review” is more for the manager to share any intel they have from being able to see what’s happening in other groups rather than to “approve” them.

This can be a peer review instead. Teams can share their OKR sets with other teams to get feedback and raise awareness of what the teams will be focusing on. This encourages greater autonomy and a less hierarchical workplace.

Have a Short and Iterative Review Process

Within forty-eight hours of the company OKRs being set, the rest of the company should be able to publish their OKRs. I’ll say it again: THE BEST IS THE ENEMY OF THE GOOD. A short review process—twenty-four hours if possible—allows teams to look at what other people are doing and adjust their own OKRs or critique others. Anyone can critique anyone else’s OKRs: this should be a process in which the entire company is helping everyone in the entire company get better. We succeed together, or not at all. After this window closes, you live with it until next quarter when you get a chance to get better at this. Analysis paralysis is a real thing, and it’s critical to plan to avoid it. Get OKRs into play so you can learn how to do them better next time.

Of course when you review, you may find someone is working on the same problem your team is. IT’S OKAY. I recall chatting with Google Ventures partner Ken Norton about when he first started at Google. Google was already huge at that point and they had an unintuitive approach to duplication of effort: they believe that there is no way to know what team will succeed and how they will succeed, so don’t worry about duplication until you have multiple successful options. I think this is the right way to look at innovation: It’s more important to be effective than efficient. Efficiency kills innovation.

There is a schedule that looks a bit like this (some steps will be familiar by now):

- Grade OKRs two weeks before quarter ends (there are very few hail Mary’s possible in the last two weeks, unless you’re in sales). Determine if you should move to the next expected Objective, change it, or have a do-over.

- Annual OKRs are set by execs, typically at an offsite (for focus reasons).

- Two weeks or so before EOQ, the execs set company OKRs. This will be a two-hour meeting once you’ve got the hang of OKRs, but at the beginning of your process, reserve more time. I recommend scheduling three, two-hour meetings, and think how nice it will be to cancel them if you don’t need them!

- Publish company OKRs a week before the quarter ends. Teams and departments set OKRs.

- Publish team and department OKRs (if departments have them).

- Short review period

- Short revision period

- Hit the ground running on day one of the new quarter.

This is the only way to scale OKRs without dragging your company to a halt every quarter. It requires you to do several brave things:

- Hire well

- Set clear outcome-based goals

- Give up control of tactics to achieve company goals

- Trust your teams

But if you don’t have trust, OKRs aren’t going to help much anyhow.

Buy the book today

The updated version of Christina's book, Radical Focus, includes 22,000 words of all-new material designed to help OKR users in larger companies create, grade, and manage OKRs in ways that accelerate success and drive rapid organisational learning. Buy the book to learn Christina's powerful system for attaining your most important goals with radical focus.