What's a product pro to do when the people around them in their business just don’t get it? It’s a common-enough occurrence: a recent report from digital product agency Planes Studio Why product-led organisations move forward with confidence highlights some of the blockers that stop organisations from running successful product processes. Fear of experimentation, lack of understanding of product management and numerous barriers to implementation figure strongly.

The report finds that:-

- 44% of product leaders don’t feel adequately empowered to fulfil their role to the best of their ability due to fear of experimentation within their business.

- 61% of product leaders at large orgs mentioned silos, BAU or competing teams and resources as a barrier to implementing product processes.

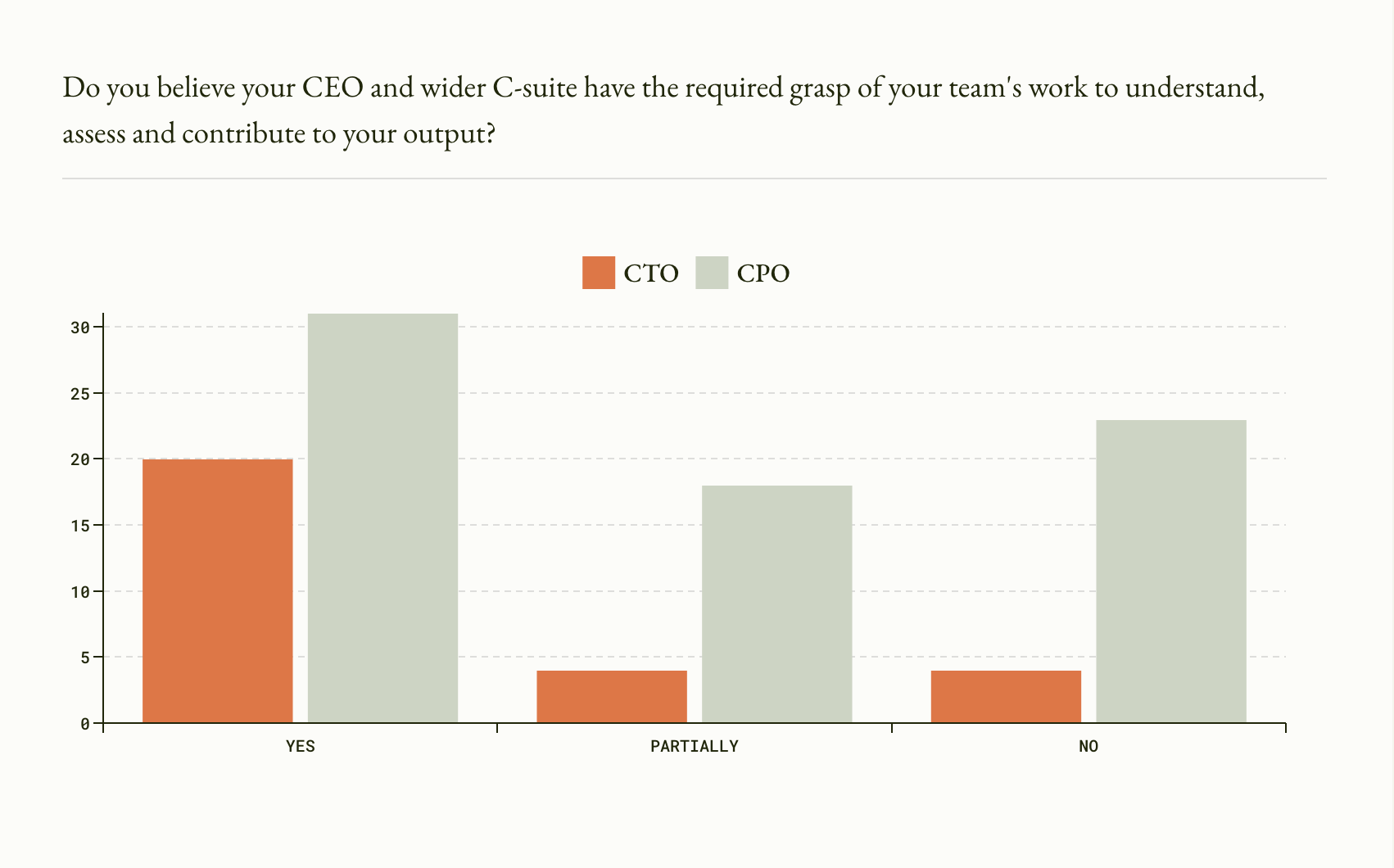

- Nearly half (42.6%) of product leaders don’t feel confident that Product is adequately understood in the C suite.

We spoke to some product leaders about their experiences of trying to “do Product” in an organisation that doesn’t understand it and to see if they might offer some advice.

Becky Yelland is Product Director at Arenko Group and has had her share of working for businesses that weren’t product friendly. She comments: “Over the course of my career, I’ve found that people say they like Product, they like the process and they buy into it. They might believe it, or they might say it because their investors have told them that they have to put some process in place.” But she’s also found that if you start introducing new processes – and all the time and effort and thought that goes with them – you will probably get some resistance and pushback.

“Who do you think you are?”

Becky remembers one experience in particular, over 10 years ago, when she was working for the UK subsidiary of a US financial services company. “In my first week the head of data science in Europe shouted at me that agile was lunacy, no one needed it, and who did I think I was. It was really toxic from the start.”

The US parent company “did product in a very old-school, laborious and process-heavy Six Sigma sort of way,” she says, but the UK business was run as a separate entity. She had been hired by the UK CMO to represent Product at a senior level in the business but on joining, found that no one in the European senior management team believed the CMO should be doing this.

She had to work out how to survive and at a stretch thrive in the role, and assess honestly what she might be able to achieve. It meant distancing herself as much as possible from the toxicity around her and looking to make improvements rather than “seismic changes”, she says.

There was little she could do to sidestep the processes being pushed from the US, so she ended up focusing on building a team – on communication and pulling a disparate group of people from across Europe together to act as a team. She says: “I used the budget I had for travel, to make sure people spent time together. They built relationships with each other, they began to feel like a team, we did training together as a team.”

It was all about finding the path that she could tread without too much friction, what wiggle room she had and what changes she could make. “By the end I felt I'd achieved something because the team felt that they were a team. We'd also introduced early-stage agile, rapid prototyping and proof of concept processes, and that was allowing us to get advocacy and buy-in from the US for new ideas.”

Common scenarios

Merissa Silk, now Principal Product Manager at Onfido, has worked for a number of businesses over the years where she’s been the first product manager or been tasked with introducing product processes. In her experience there are a number of common scenarios in organisations that do Product in an imperfect way, usually to do with roadmaps, sales teams or delivery.

She says that too often, product managers are left out of strategic prioritisation conversations and given a final version of the roadmap. The sales team may also wield a lot of power. Says Merissa: “Product managers will always find themselves fielding inbound requests from sales for ad hoc feature requests, especially when money is on the line. These requests almost always come to product managers as fully-baked solutions, sometimes with wireframes or designs, prescribing the look and feel and the UX.” It may also be that the focus is entirely on delivery, leaving no room for discovery, experimentation, and learning. Merissa adds: “In delivery-centric organisations, 'discovery' is a big word and can even feel confronting to senior leaders. After all, if teams are discovering things senior leaders believe they already know, product managers are wasting precious time that could have been spent on delivering.”

Some or even all of the above will sound very familiar to most of you. After all, when is Product ever done perfectly? But what can you do about it?

Look for red flags

You may think you'll have advocacy and support in the C-suite from the start of a new job, but this is often far from the case. Put in the work before you start, Becky Yelland advises, make sure you understand who the product advocates are in the senior leadership team. This is even more vital if you’re a product leader, she says. She’s had jobs where everything sounded and felt completely right in terms of product as a discipline, but which nevertheless haven’t been plain sailing. “Someone knocking at the door of the C-suite and challenging the senior leadership team in terms of time, effort and approach may not be something that they’re comfortable with,” she adds. She always tries to understand the leadership team’s journey to making the decision to bring in product leadership – who made the decision, how it was made, and the expected outcome. “And even if you hear the right things, it might be that the reality of what that means, the cost and the investment in terms of time and effort, might not have been understood,” she says.

If there are only one or two product advocates in the C-suite, then there will be conflict, Becky says. You’ll constantly have to demonstrate and prove that Product works.“And if you think you’ll be educating the entire organisation about Product, ask yourself if you're ready or want to do that,” she adds. She also advises to not only speak to the business’ leaders, but also to people in the product team: “It’s much easier to ask probing questions to people at ground level than those who are perhaps more well-versed in toeing the party line.”

Planes Studio Co-founder and Head of Product Ryan Lock says that you only need to ask one question to understand the maturity of a product organisation: how are decisions made? He says: “If feature decisions are made by a HiPPO, or behind closed doors, you might be in for a tough ride. If decision-making is clearly made based on the needs of both the business and customer – golden.”

First steps and quick wins

If you find you’re having to be a champion and educator then Becky advises a bit of name-dropping. Show people what has been achieved through adopting product methodologies and processes. “It helps people understand that you're representing a well-trodden path as opposed to somebody coming in with new ideas.” Ryan also advises that you don’t go evangelising on day one. “Instead, deliver something. Do something that other people will find valuable, even if it’s not a ‘perfect process’. You’ll build trust, which is the most important starting point for change.”

Roadmaps: Merissa comments that even though product managers might be told at a high level what to build and in what order, they're rarely told how to do it or what the final product should be like. You can facilitate important conversations about what problem a feature is solving, who the audience is, how the functionality will be designed and delivered, and the go-to-market strategy. You can also define the success metrics and develop a more detailed roadmap for how the feature will grow over time, of course, based on the data collected.

She observes that planning and roadmap conversations often happen according to a set cadence. Once you learn the rhythm of the business, you can use the data you have about the products and the market to influence roadmap conversations before they happen.

Customer feature requests: Becky says she mentored lots of product managers who have found themselves in roles with a Frankenstein product or platform with lots of features built for specific customers. They’re delivering to customer asks and needs and the backlog is very much defined by customers and sales. The sales team coming to Product with feature requests will feel disempowering and frustrating – but Merissa points out this can be a teaching moment. She says: “You can bring a product mindset into these moments and skillfully shift the conversation from solutions to problems.

She says you might ask questions to the sales team like:

- What problem are they trying to solve? How do they know it's a problem?

- How painful is that problem? How big (in terms of users or frequency) is that problem?

- How are they solving that problem today? Where is the current solution falling short?

- What would success look like? How would you know it's 'working'?

Ideally, you'll be able to get in front of the customer and ask these questions directly. And if that's not possible, you can give your customer-facing peers open-ended questions to ask their stakeholders.

She suggests creating a template to use to help sales staff structure customer requests, her feature template is here. Filling the template can happen together at first, she says, and once the sales team is comfortable, the completed template can become the jumping-off point for more detailed discussions with salespeople and customers.

Delivery: If Product is focused on delivery to the detriment of discovery, then the trick here is to reframe, says Merissa. “You're not discovering, you're de-risking – and thanks to the cross-functional nature of product teams, this can be done alongside delivery, as different roles focus on their expertise.” She says that for B2C products, friends and family testing or guerilla testing can be a great way to gather micro insights about your designs. For B2B products, product managers and designers can leverage peer relationships to bring prototypes to upcoming customer meetings. She adds that no one wants to deliver a product that flops, you need to find ways to get incremental learnings and de-risk each phase of the delivery: “Don't ask for permission to conduct research – simply find ways to de-risk while you're delivering.”

Becky says that all the struggle is worth it for the times you get it right and you can actually make a change, even in the most toxic or uninspiring of environments. “Looking back, the things that I focus on are the small impacts that I made on someone's career,” she says. She remembers someone from her time at the financial services company when she championed someone who had been “buried in the IT team for a significant amount of time”. “I just saw something in her and encouraged her to come into my team. She did, and she's still in Product and still loving it today.”

More great content like this in Mind the Product

Product manager zero: When to hire the first product manager

Your first 90 days in product – Leah Tharin on The Product Experience