I was sitting in a cafe in Brighton a few months ago, having breakfast with Andy from Clearleft. We were talking about I thing I was working on, and I’d used the word ‘fidelity’ to describe how close a project was ‘to the real world’ specifically in terms of people, rather than products.

We talked for a while about what fidelity typically meant in general design and usability circles, and a a result, I went away to think some more. Chats with Andy usually work out like that.

It turns out that fidelity is a tricky word. It comes from the same etymological well as faithfulness and loyalty, and the broader concept of fealty. We talk about it in terms of our behaviour; how faithful (or otherwise) we are to partners, friends, practices, ideals.

In this respect, the object comes first, and our fidelity to the object is judged from that point onwards. We look backwards.

When we use the term fidelity to anthropomorphise other things, we see again that it is a concept that’s used to compare what we have in front of us to what happened before.

For instance, fidelity in audio is about how closely the sound we’re hearing compares to the sound and the point of recording. High fidelity, or “hi-fi”, was so great because it sounded like you were actually there.

And in scientific disciplines, fidelity in modelling refers to how well the simulation reproduces the state and behaviour of the real world object (which has existed for millennia perhaps).

Yet, because of the nature of the design process, when we use the word ‘fidelity’ to describe how close we’re getting to a final product, we are using it not to compare to what we have seen in a known past, but to something we imagine in an estimated future.

When we describe a “low-fidelity prototype” for instance, we’re not comparing it to something in the past, but something still quite far away in the future.

We are not comparing, we are guessing. Of course, these may be very good guesses, based on sound practice and great experience, but they are guesses nonetheless. It may be because of the way we view time as part of the design process.

There are three useful examples of design processes highlighted in the Sketching User Experiences Workbook (Buxton, Greenberg et al). I won’t dive into the detail of each of the models, but have a look at what unites the three…

It’s time. Time is used as a tool to tell us what we should be doing, and when.

These three design models (and many more besides) all move along an X axis, left to right, from the beginning of the project to the end, as if the process itself is as predictable as a written sentence. This might have a big implication that we perhaps might be better doing without.

When the model you use is locked onto a time axis, there is not much room for other dimensions, especially if you’re only working in 2 dimensional models.

Typically, the other axis in all of the models above is being used for ‘activity’; what are we going to do when. A time-based model has a presumption of good practice, that you will regularly put things of front of people to test, in different ways to validate different things.

That’s not always the case though. With clients who work in a different system, or even when circumstances get the better of you, good disciplined practice can slip, as activity just starts to mean “we must get to the end bit of the model”.

What’s the solution? Well, what follows isn’t perfect, but it’s a useful start. It’s something we’ve been working with for the last few months, and it’s a broad tool for thinking, of which this is just one application (you can read some background here).

It’s a model which uses two different facets of ‘activity’ in order to help remember that we always have one of two choices; Improve or Share.

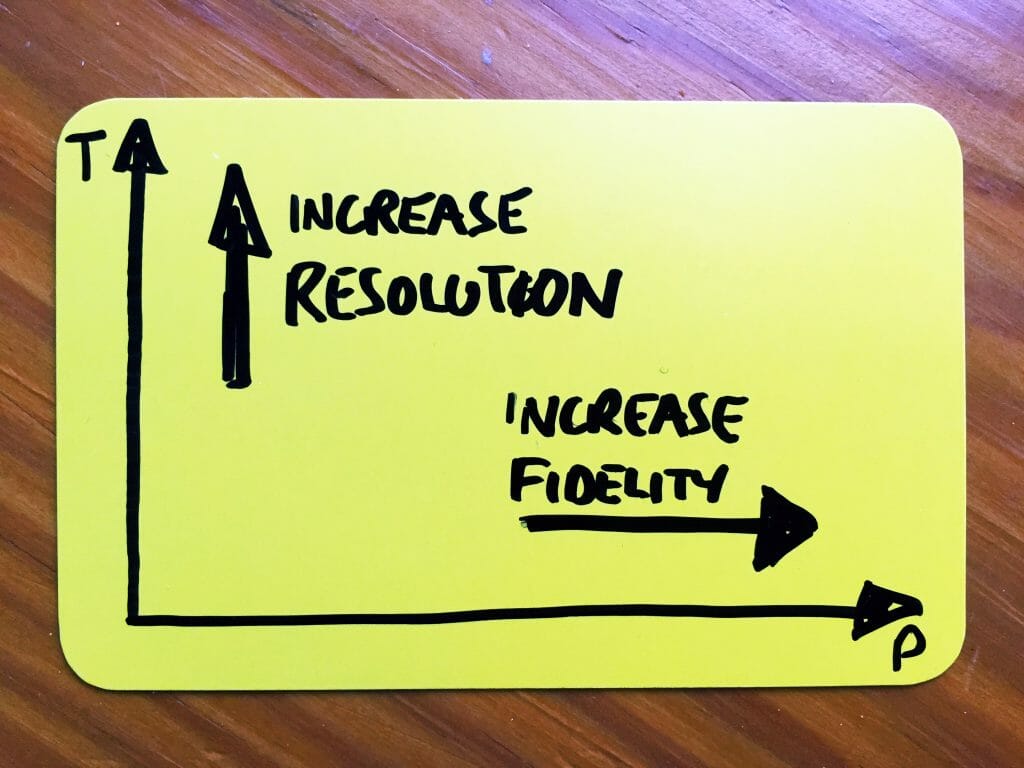

Along the horizontal axis, we have ‘people’, and up the vertical axis, we have ‘things’:

For us, fidelity is all about the people axis; how close is this to the real world? That’s the future point, when the product is out in front of lots of people, being used often, at scale. If you want to increase fidelity, then you show whatever you have to more people.

Which leaves the vertical axis, things, to be all about resolution. Resolution is a much more technical description of what we have in front of us, used across many different fields to describe the detailed specifications of what the thing involves. It’s been much more useful when you’re using that language around the thing you’re working on.

That’s the territory the model describes, but how do we use it?

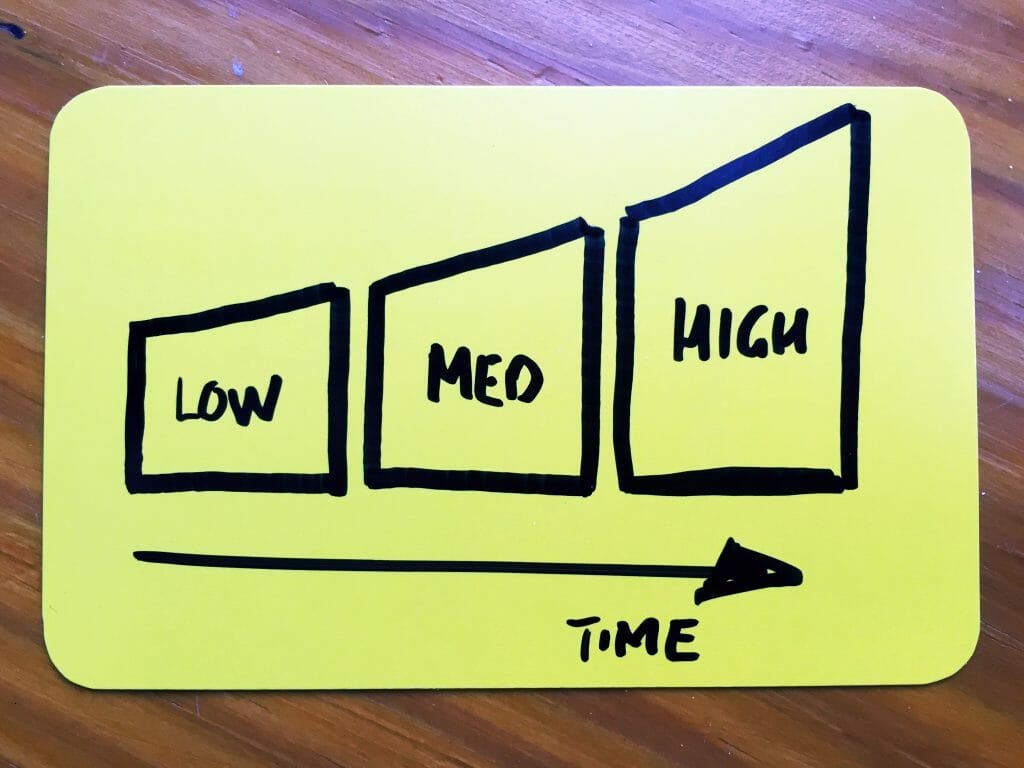

Take the familiar mechanics of Low, Medium, High. If we had a time-based axis from left to right, they’d line up in their familiar form, like below:

In this model though, we can use Low, Medium and High to describe both Fidelity and Resolution. Rather than a three-step process, we can create a nine box grid.

Notionally, Low sits bottom left, Medium in the middle, and High is top right. But they’re now more like places to visits, rather than territories to cross. We’ve been thinking of each axis in the following ways to determine the sort of activity we do.

People

Low Fidelity – very simply, the people in the room, the project team. It’s as far away from the real world as you can get, and you should always remember that.

Medium Fidelity – sharing your ideas qualitatively. Face to face user research, talking to people in different parts of the business, talking to experts.

High Fidelity – sharing your ideas quantitatively. Everything from the tried and tested trick of putting up one web page about a product and buying search ads for it, to in depth quantitative research to test a specific hypothesis at scale.

Things

Low Resolution – working on pens and Artefact Cards, LEGO and plasticine, Stickers on Boxes; anything that create fast physical space to create a representation of an idea

Medium Resolution – working on surface detail to create simulations and wireframes of things, but not anything that actually works yet

High Resolution – building out the back end, both from a technological and business perspective; how is it going to work, and how is it going to make money to be sustainable?

We always start bottom left, small teams of people working in physical materials to create rough representations. Then the crucial part of using the model kicks in; you have to choose what to do next. Are you going to take those representations, and put them down in front of people for qualitative feedback? If so, then you should share. Alternatively, are you going to take the ideas away, spruce them up a little, sweat the thinking a bit, perhaps? Then that’s fine too, you’re talking about improving.

At every stage on the journey through the process, you stop and ask “should we share, or should we improve?”.

By stripping out time from being one of the axes, we introduce a sophistication which informs the process at every step. But time hasn’t been lost from the model altogether. Instead, it becomes a more passive data source, as you draw out your process across the territory.

For example, below we can imagine two different journeys across the model:

The red journey has a lot of early stage test and learn; make things, show them to people, rinse and repeat. The blue journey perhaps takes the first set of concepts, tests them with people to pick one, builds a wireframe, tests it quantitatively, and gets ready to ship. The red journey is long, the blue journey is short. But they’re different projects, there’s no law that says they should be the same length of time… unless, of course, your process demands it.

So far, this model has proved very useful both conceptually and in live projects, but we’d love to hear what you think. How do you think about fidelity? Do you see an enforced sense of time in a design process as a hinderance, or a benefit to keep things moving? Can you see projects you have worked on (or are currently) fitting into this model?

Comments

Join the community

Sign up for free to share your thoughts