Roadmap creation is one of the primary jobs of a product manager, and probably the one that causes them the most difficulty. There are many books, blogs, conference talks, and training programmes on what makes a good roadmap, and people make careers out of being roadmapping experts. It’s impossible to distill all this valuable information into a single article but hopefully this post will give you enough useful advice to set you on the path to successful roadmapping.

The Definition

Let's start with a definition: what is a roadmap? While there are plenty of definitions for a roadmap, as ever, it’s the simplest that are the best. We can define a roadmap as a visual document that shows the steps you intend to take to realise your product vision over time.

What Makes a Good Roadmap?

A good roadmap is geared towards outcomes rather than outputs, “outputs are outmoded as a way of thinking” says Bruce McCarthy, author of books on roadmapping and founder of Product Culture, in a Product Experience podcast on Roadmaps, OKRs, Vision and Prioritisation.

Scott Colfer, head of product at the UK’s Ministry of Justice, argues that the roadmap is shorthand for product management to the rest of the organisation, and he’s created a diagram to help explain what makes a good roadmap in an MTP post Product Roadmaps in Five Easy Pieces. You can also use the diagram as an aid to talk about the core concepts of product management with workmates, he says.

Janna Bastow, MTP's own roadmapping guru and CEO of ProdPad, advises that a good roadmap has to be visible and easily accessible to everybody, it’s no good just sticking it in a folder for people to find. A good roadmap should continuously evolve and be revised whenever you learn something new. Visibility means that developers can see what is coming up the pipeline, she says, what the current problems are and what the future problems might be. “You should make sure that your assumptions about the future are documented and made visible to the rest of the team – somewhere that is user friendly,” says Janna, “the roadmap should be part of the vocabulary, it should be a living document.”

The Components

Much of the difficulty with creating roadmaps comes from the way they are constructed. Historically people have tended to list the features they want to build, estimated how long it should take to build them and called this their roadmap. As MTP’s chief of staff Emily Tate says: “This is what a lot of stakeholders want out of roadmaps because it gives them a sense of certainty, and they can tell customers when the feature they’ve been asking for will be ready. But a roadmap built this way never happens, because we estimate poorly.”

Emily tells the story of her time at travel organiser app TripCase to illustrate this point – planning would start in August for the next calendar year and then she would update the roadmap throughout the year, responding to the market and updating for features that took longer than expected or no longer made sense. “At the end of one year, I went back and compared what our roadmap actually looked like to what we thought it would look like at the beginning of the year. We had only completed 20% of what we thought we were going to do in January.”

Starting with the features you want to build may seem appealing and easy for everyone to understand, but it’s not the way to create a usable roadmap. It’s much more effective to take a step back and consider the goals of the product and construct a roadmap from there.

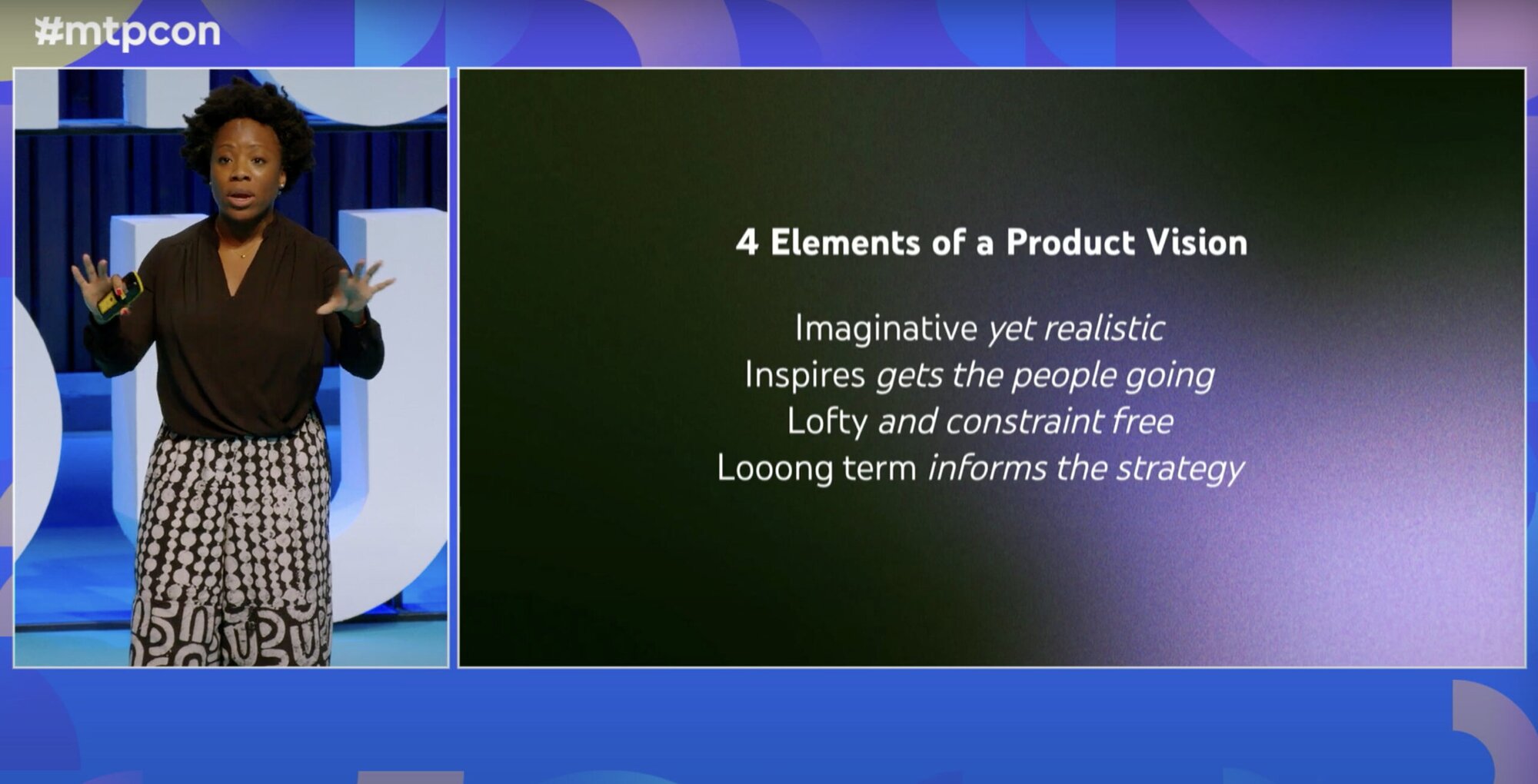

Current thinking is that there are five essential components to a roadmap: the product vision, business objectives, timeframes, themes, and a disclaimer. You can watch Roadmaps are Dead! Long Live Roadmaps! – C Todd Lombardo’s 2018 #mtpcon talk – for lots of great detail on what the components should be, but here’s an overview.

Product Vision

The product vision is, to quote Roman Pichler, the overarching goal you’re aiming for, the reason for creating the product. It needs to be easy to communicate and to understand. Product managers need to own their product vision and push towards it.

Roman says that “to choose the right vision, ask yourself why you are excited to work on the product, why you care about it, what positive change the product should bring about, and how it will shape the future”. He says that it’s fine to choose the company vision as the vision for a product but you don’t, you should take care to ensure the two visions are aligned. He has more advice on how to create a compelling product vision in his blog post, 8 Tips For Creating A Compelling Product Vision. It takes time and careful crafting to create a product vision.

In this Product Vision vs Mission blog post, Marty Cagan writes that “most people I meet, when they show me their 'product vision', what they are really showing me is their ‘mission statement’. They are confusing a slogan about their purpose, with a product vision”. He has some useful guidance on what a product vision should be and says that “an inspiring and compelling product vision serves so many critical purposes that it is hard to think of a more important or higher-leverage product artifact”. He says a good product vision keeps us focused on the customer, shows us why the work is meaningful, and gives us a common understanding.

Business Objectives

Business objectives are necessarily an integral part of the roadmap, and the product vision needs to be tied to business objectives and key results. You need to articulate what your product will accomplish and how it will be different.

Here’s a helpful paper from Tim Herbig on how to combine OKRs and agile product management.

Timeframes

Roadmaps explicitly carry an element of time. Timeframes help you to prioritise, but historically there’s been a lot of uncertainty about how to include timeframes on a roadmap because deadlines can tie you down and push you into building for its own sake, rather than building the right thing.

A timeline roadmap simply doesn’t leave room for discovery and iteration, and at the end of the day, makes the product person look bad when delivery fails or the wrong product is built.Janna Bastow

The advice from roadmapping experts is to keep timeframes as loose as you can. Janna strongly advises product managers to think in terms of time horizons in this post, Free Your Product Roadmap and Ditch the Timeline – she suggests current, near-term, and future – rather than a strict timeline format because “a timeline roadmap simply doesn’t leave room for discovery and iteration, and at the end of the day, makes the product person look bad when delivery fails or the wrong product is built”.

Themes

Themes are a promise to solve problems rather than build features, in the words of product usability guru Jared Spool. Starting with themes helps you to establish priorities that the whole organisation can understand because you look at the problems that need to be solved now. This blog post from ProdPad, How to Build a Product Roadmap Everyone Understands, contains some useful advice on building themes or initiatives.

Emily comments that the philosophy around themes is that you commit to solving the problem rather than committing to a solution. She gives the example of onboarding from one of her previous roles: “We’d done some research and we had a hypothesis for what a new user needed to do early in their journey in order to recognise the value of our product. So we had a goal for what we wanted new users to complete in their first week of using the product. But rather than declare up front what feature we would build, we put a block in the roadmap for onboarding. We gave people a block of time to test as many ideas as they could to see if they could solve the problem of improving our onboarding flow. We didn’t go into that effort with an idea of what the solution should be.”

Disclaimer

It may seem a minor point, but as C Todd explains, a roadmap is a forward-looking statement and of necessity is subject to change. A disclaimer on the roadmap helps to manage expectations. A disclaimer makes it clear that change is possible, and clarifies whether the roadmap is for external consumption or for internal use only.

Different Types of Roadmap

In practice there are different types of roadmap – single product, multiple product, unified roadmaps showing collaboration between teams, internal and external roadmaps, and so on, depending on the audience the roadmap is intended for. This Medium post, The Most Effective Product Roadmap Types You Need To Know, runs through the common types of roadmap.

It pays to really think through how useful these different types of roadmap might be, however. As Emily says: “Before you pull out a template you should decide why you're building the roadmap. Is it to keep us in the development team aligned? Is it to talk to customers? Is it to present to internal teams? What is going to be the best format to facilitate the conversation?” Emily says that, for example, she’s created a multiple product roadmap in order to evaluate any common dependencies, but warns that they can be unwieldy if you try to do too much with them.

Before you pull out a template you should decide why you're building the roadmap.Emily Tate

Creating a Roadmap

There are lots of product management software tools available which aim to take a lot of the pain out of roadmap creation. In one of her early ProductTank talks, Guide to Roadmapping, Janna provides some useful tactics for moving through the steps to create a roadmap.

It’s important to bear in mind that the roadmap is a prototype. This means there’s no need to get hung up about creating a perfect-looking roadmap, it just needs to work for your stakeholders. What’s important is the value you get out of the creation process itself, the communication and checking of assumptions with other people in the organisation.

A roadmap needs to be reviewed regularly, and that means different things for different teams and products. Obviously, if your team moves at a breakneck pace then the roadmap needs to be revisited more regularly than in a slower moving business. Though, as our experts comment, product people should always aim to recheck their assumptions as they learn.

Who’s in Charge?

Ideally, the product manager should own the product roadmap and the innovation to prioritise. The product manager should collaborate with product owners, technology leadership, and the CX / UX function.

However, this is not always achievable. In smaller organisations or startups, there may be only one or two product managers to drive the roadmap. Large enterprises will have many product managers under product management leadership and the roadmap may have multiple owners.

As Mike Gadsby, co-founder and chief innovation officer at digital product company O3 World, says: “The challenge is that not all product management functions are defined the same way and depending on the complexity of the product and experience, the roadmap might include adjacent functions like marketing and support.”

Khadijah Abu, head of product at Paystack, adds that product managers are essentially not just the owners of the product or feature being built, but also a communication interface between their product team and the internal stakeholders, because they often do not speak the same language, and someone has to translate.

Getting Alignment Around the Roadmap

Regardless of the size of the organisation or the complexity of the experience, says Mike Gadsby, the roadmap needs to equally represent insight from strategy (what do people need), marketing (what do people want), UX/CX (what do people experience) and technology (can it be built efficiently and effectively) to drive product success. He says that enterprise products that suffer from a lack of alignment often lean on one or two of those branches and disregard the others.

Getting buy-in from the company itself is the key to alignment. Mike adds: “To ensure continued alignment organisations must develop a culture and prioritise criteria and processes that support and require all four functions. This is typically a top-down challenge that requires buy-in and support from senior executives.” Janna comments while individuals can understand the need to align around a roadmap, companies want steady quarter-on-quarter growth. She cites Blockbuster passing up the opportunity to buy Netflix and sticking to its bricks and mortar model as an example of a company choosing not to solve bigger and better problems.

At Paystack, says Khadijah, getting alignment on product roadmaps comes through;

- Ensuring that internal stakeholders are part of the planning process

- Sharing roadmap plans early and often

- Being upfront about constraints, delays and changes to plans

She adds: “A culture of transparency and accountability, combined with real-time collaboration tools like Slack and Notion, allows knowledge and updates to be shared with the entire organisation, which ensures that we get robust and critical feedback early and prevents avoidable delays that often result from information asymmetry. But while it's easy to focus on the product development and release cycle, we believe sharing plans often should also be matched by sharing wins and achievements often.”

Paystack has a dedicated Slack channel that is used to celebrate new product improvements, and the company holds quarterly demo days where each product team shares what they shipped in the previous quarter, and what they've got in the pipeline for the next one. Says Khadijah: “The recurring dopamine hit from frequent micro wins keeps the product teams motivated, and keeps the rest of the organisation excited and supportive about the things we are building.”

Common Problems

People get very stuck creating roadmaps, despite all the available advice and information on the topic. Clearly there’s something wrong if people find them so difficult to create, and continue to ship the wrong thing.

Why do we find roadmaps so difficult? The answer is, say the experts, that there are widespread misconceptions over what they should be and a lack of understanding over what makes a good roadmap. “Product people often don’t get any training,” says Janna. “They don't come from a product background and have fallen into it. Their boss asks them for a roadmap and so they Google it and look for templates. They get all sorts of Gantt-type charts, lists of feature after feature, and timelines.” It’s a scenario that leads the product manager to estimate when a raft of things will be done and lay them out in some sort of chart, and call it a roadmap. John Cutler in this Medium post, Stop Setting up Product Roadmaps to Fail, examines some of the debate around roadmaps and why they fail.

Remember that a roadmap should be a strategic, visual document for high-level communication and discussion of the product vision and intended steps to arrive at this vision. It should lay out the work required to meet business objectives, and should be kept separate from planning documents such as lists of features and backlogs. Its value lies in its use as a communication tool, so that everyone – product people and stakeholders – can see and articulate the steps needed to meet the vision. The vision should always be further reaching than the roadmap, the roadmap serves to give clarity, to check everyone’s understanding of the vision and the problems that might be met along the way.

With this in mind, says Janna, the most practical way to understand what a roadmap is, is to take a proper look at what it isn’t. A roadmap is not a short-term release plan or a list of features to tie a product manager down. As C Todd Lombardo says, “a roadmap is for outcomes, a release or sprint plan is for outputs”, because you might finish a project or sprint, but your product is never done.

Without a roadmap, you rely on everyone to be instinctively aligned and to interpret the product vision in the same way.

Without a roadmap, it’s easier to stick to picking the low-hanging fruit and refrain from tackling the bigger strategic stuff.

Without a roadmap, it’s easier for other parts of the business to interfere and hijack objectives and priorities.

Some businesses find it simply too hard to deliver a roadmap and just don’t have one, relying solely on OKRs instead. However, as Janna says, “OKRs work best in conjunction with some alignment with what's on the horizon”, and when a team only relies on OKRs that ability to align on assumptions is lost. “It means the team lacks the ability to check assumptions over the obstacles ahead of it,” she says.

Summary

In summary then, your roadmap should be a high-level tool for showing how you intend to realise the product vision and you shouldn’t make it a list of features and time frames, no matter what pressure you’re under to do so. A roadmap is a means to get everyone to think about your product, so you should think about who you're sharing it with and then develop your vision, your objectives, and the problems that you need to solve. Then consider the time frames in which you want to solve the problems. And remember that it’s all subject to change – a roadmap is a discussion document to check assumptions and make sure everyone's aligned, it’s not a release plan.

Further Reading and Resources

- How to Sell Your Boss on Roadmaps Without Timelines by Janna Bastow

- Creating Good Roadmaps: 6 Practical Steps for Product Leaders by Matt Walton

- Escape From the Feature Roadmap to Outcome-driven Development by Alice Newton-Rex